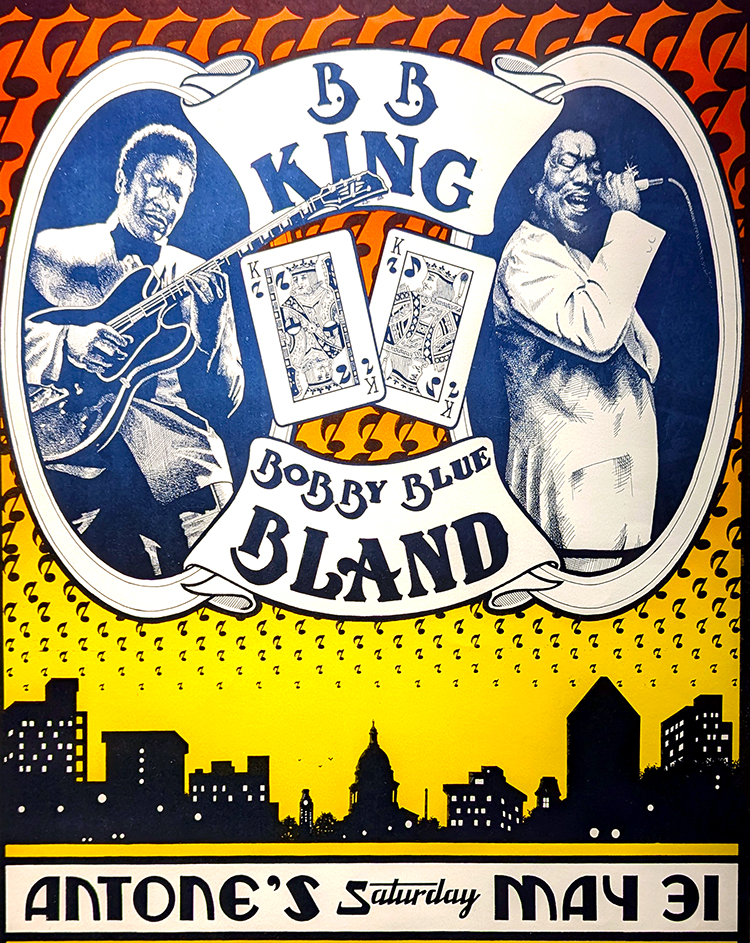

Poster promoting BB King and Bobby Blue Bland appearing at Antone’s in Austin, circa 1980(?)

Attempting to trace the development of American music from the 1600s onward in one exhibition is an ambitious undertaking. In my mind, it’s too big a chunk to lump together.

Yet a visit to “Music America: Iconic Objects from America’s Music History” at the LBJ Presidential Library until August 11 is well worthwhile. Somehow the clever curation by the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music includes enough variety for broad appeal, a combination of instruments, costumes, listening stations and videos all contributing to the experience.

The presence of some awesome guitars was not what perked my attention like the ears of RCA’s Nipper (a sentimental favorite as a stuffed one of equal size shared my single bed and guided me through childhood nightmares). Hand-written words seduced me into examining lyrics without soundtracks and begged me to dig deeper at home afterwards.

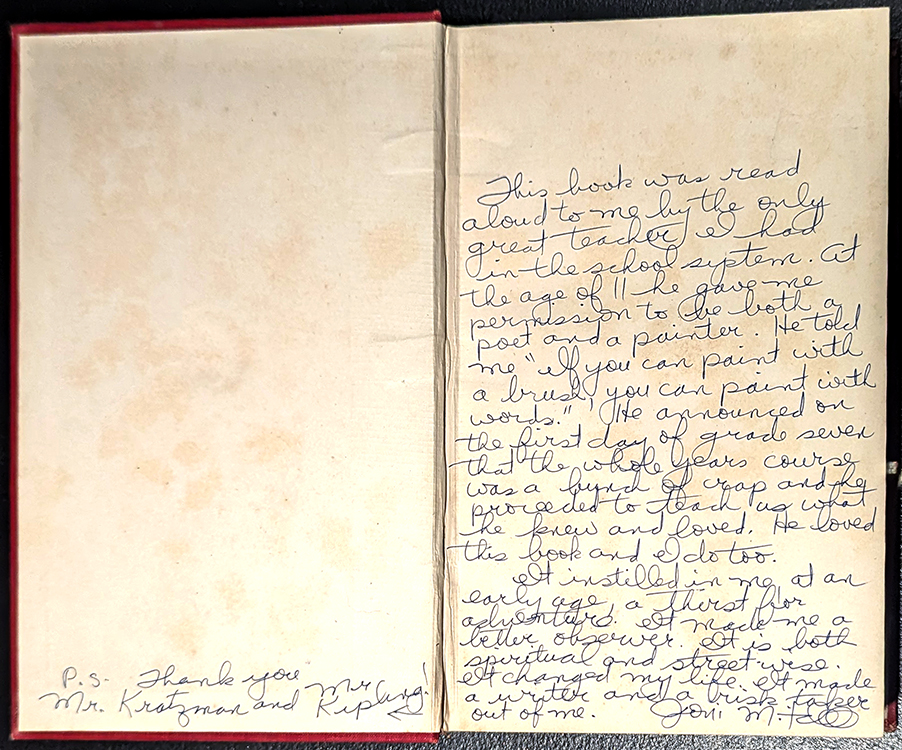

This book was read aloud to me by the only great teacher I had in the school system…. He gave me permission to be both a poet and a painter….

It instilled in me, at an early age, a thirst for adventure. It made me a better observer. It is both spiritual and street-wise. It changed my life. It made a writer and a risk-taker out of me.”

Above: Joni Mitchell’s inscription in a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, from the collection of Barry and Judy Ollman

Returning home I found myself wondering about Kipling’s long-term influence on Mitchell’s writing. Years later it bubbled up to the surface in her 2007 adaptation of his poem, “If.”

If you can keep your head

While all about you

People are losing theirs and blaming you

If you can trust yourself

When everybody doubts you

And make allowance for their doubting too.

From Joni Mitchell’s 2007 adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s 1895 “If”

But what really caught me off guard was the rambling, poetic letter penned by Johnny Cash to Bob Dylan in 1969.

The North wind turned into a twister, picking up one Bob Dylan, took him south, east, west, dropping his berries into everybody’s fruit cocktail. To some he tasted bitter…. Some he shaped and fashioned into puppets, but my friend Bob, you had more strings than you had fingers…. You’ve still got enough strings left to handle puppets. The World is still your apple.”

Above: Excerpts from 1969 letter from Johnny Cash to Bob Dylan, from the collection of Barry and Judy Ollman

In the summer of 1969, Johnny Cash was not playing on the record players of anyone I knew. He was “country,” and country wasn’t cool. Not that I was. It was the time of Woodstock and protest songs.

The anthem my friend Jewel and I would sing out over and over was:

And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for?

Don't ask me I don't give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam.

And it's five, six, seven, open up the pearly gates,

Well, there ain't no time to wonder why,

Whoopie! We're all gonna die!

Excerpt from “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die Rag,” Country Joe and the Fish, 1968

The premier of The Johnny Cash Show was not on our radar. But the curator notes at this exhibit referenced the guest stars, including Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan. How did we overlook this? Of course, I left the library and looked for the show on YouTube. And there was Joni. Dylan’s segment is cut from this for some reason, but Cash and his wife, June Carter Cash, do perform a duet of Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe.”

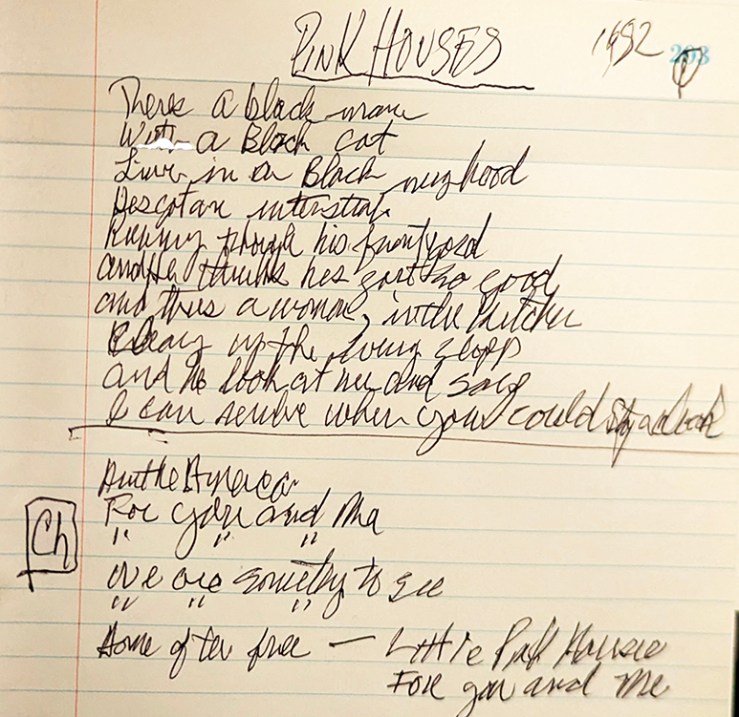

Handwritten lyrics of numerous protest songs through the years are spotlighted at the exhibit as well.

There's a black man

With a black cat

Lives in a black neighborhood

He's got an interstate

Running through his front yard

And he thinks he's got it so good

And this woman, in the kitchen

Cleaning up the evening slop

And he look at her and says

I can remember when you could stop a clock.

“Pink Houses,” John Cougar Mellencamp, 1983

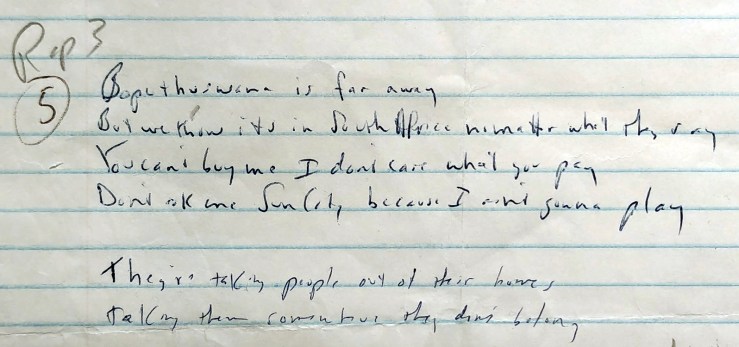

Artists United Against Apartheid was organized by “Little” Steven Van Zandt in 1985 to galvanize support opposing the extreme segregation policies in South Africa.

Boputhuswana is far away

But we know it's in South Africa no matter what they say

You can't buy me I don't care what you pay

Don't ask me Sun City because I ain't gonna play

They're taking people out of their homes

To somewhere they don't belong

Above: Excerpt from “(I Ain’t Gonna Play) Sun City,” Steven Van Zandt, 1985

“Sun City,” Artists United Against Apartheid, Little Steven

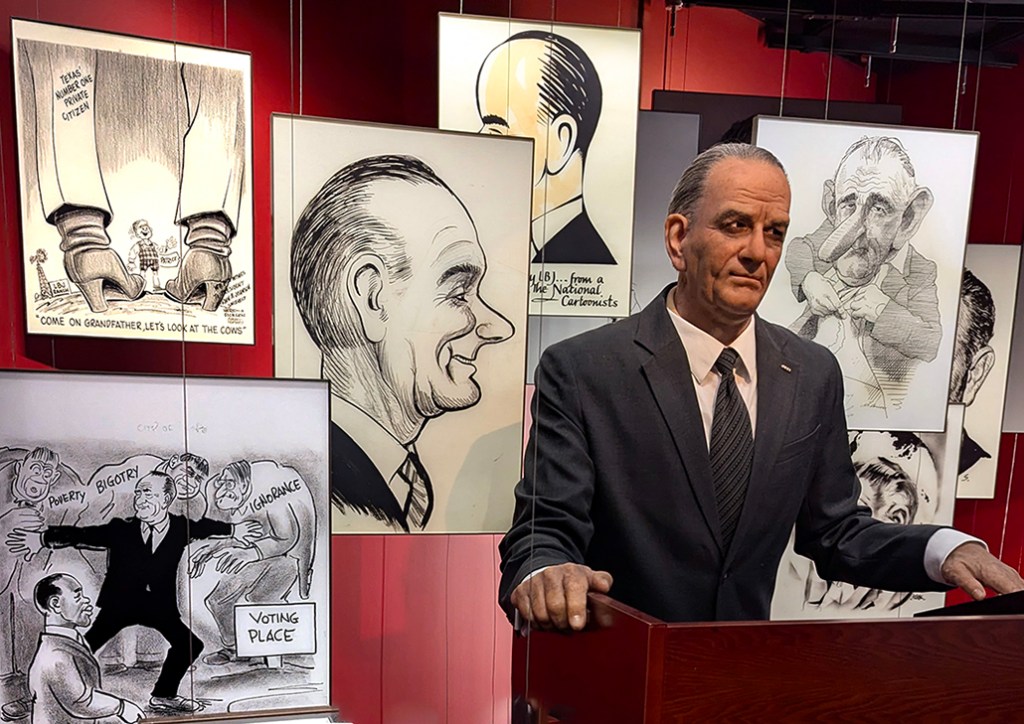

This exhibition brought forth memories of so many protest songs, making it particularly strange to visit it within the walls of the LBJ Presidential Library. The involvement in Viet Nam during the six-year presidency of Lyndon Baines Johnson (1908-1973) sparked protests throughout the country. Music fanned those flames of discontent.

Passing through the library on our way to the music exhibit, we glimpsed reminders of a different side of LBJ. His oft-forgotten accomplishments moving forward his vision for “The Great Society” were drowned out by the disastrous war. Medicare and Medicaid were enacted under his presidency. President Johnson also signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – acts so critical to reenforce during this period when regressive efforts abound to restrict voting access.

Noticing numerous items in the exhibition were on loan from the Ollmans, I was curious about the couple as collectors. I stumbled upon Barry Ollman‘s own protest song, particularly appropriate in the wake of this past week’s presidential debate and for this post: “Words Matter.”

Above: “Words Matter,” by Barry Ollman featuring Garry Tallent of the E Street Band

Thanks for mentioning Kipling’s “Kim” — Just checked it out from SAPL.

A book that got away from me in my early years.

RR

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also missed reading “Kim” in my youth. Love to hear your thoughts after you finish, Roland.

LikeLike

Just started reading this evening. I quickly realized that I need to accustom myself to Kipling’s style of writing. He finished writing the novel at the end of the 19th Century. And I only know the bare bones of the story, which takes place in the context of the rival Far East empire-building of the British and the Russians. (“The Great Game”)

I remembered that some of the story was featured in the hour-long program series hosted by Shirley Temple. I found “Kim” on YouTube and this brought back some memories from childhood (including the intro by adult Shirley Temple). It amazes me that such a sophisticated tale was considered ideal programming for children in 1960. I suppose that back then children were not universally assumed to be pinheads who only watched Deputy Dawg cartoons. Then again there were the Leonard Bernstein concerts for young people.

I probably won’t watch the entire TV production but it is helpful in establishing the setting for the story. I am very interested in how Kipling presents it.

My newfound interest was stirred by seeing Joni Mitchell’s writing on the inside cover of the book. I think that I am one of the few who still finds her albums rewarding, in particular the later CDs “Both Sides Now” (2000) and “Travelogue” (2002), both with orchestra conducted by Vince Mendoza. The last 5 tracks of “Travelogue” in sequence are perfect for clearing away the prevalent mindless clutter that pervades the news stream day after day. (even TPR does it)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Roland – You are far from alone in appreciating the lyrical poetry found in the midst of Joni Mitchell’s mesmerizing music.

LikeLike

Hey, Happy Canada Day. I am remembering the Canadian Pavilion at HemisFair. It was the most wonderful experience to me, presenting a comprehensive environment that engaged all the senses. (The interior had a clean pine scent — something that stimulated my imagination. The floor was gorgeous smooth blond wood. So different from Saltillo tile.)

LikeLiked by 1 person