Above: “Annunciation and Saints,” Jose de Paez, Mexican (1727-1790), oil on copper, 1750-1760.

“Spirit & Splendor: El Greco, Velázquez, and the Hispanic Baroque” surveys 150 years of Spanish art leading to the Baroque period with works culled from the collection of the Hispanic Society of America in New York City. Some of Spain’s most renowned and respected artists are represented in this ongoing exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art, but don’t expect much more than a dozen of these works.

What I love are the pieces demonstrating the Baroque style translated by transplants and native-born artisans in the Americas. Artists took advantage of materials available in this so-called “New” World – copper, shells and, of course, more precious metals. They added a magical sheen to art designed to convert “pagans” to the foreign beliefs held by the Catholic conquerors.

The frames of these two paintings are made of thousands of pieces of mother-of-pearl, the inner shell of certain mollusks. Skilled artists cut the shells and fit them into a layer of gesso that had been applied to the frame. The reflective qualities of the gilded gesso and mother-of-pearl would have been particularly spectacular in a candle-lit church.”

Curator Notes, Blanton Museum of Art

Above top left: “The Presentation of Christ in the Temple.” Bottom left: “The Flight into Egypt.” Oil on canvas by anonymous 18th-century Peruvian artists in Cuzco.

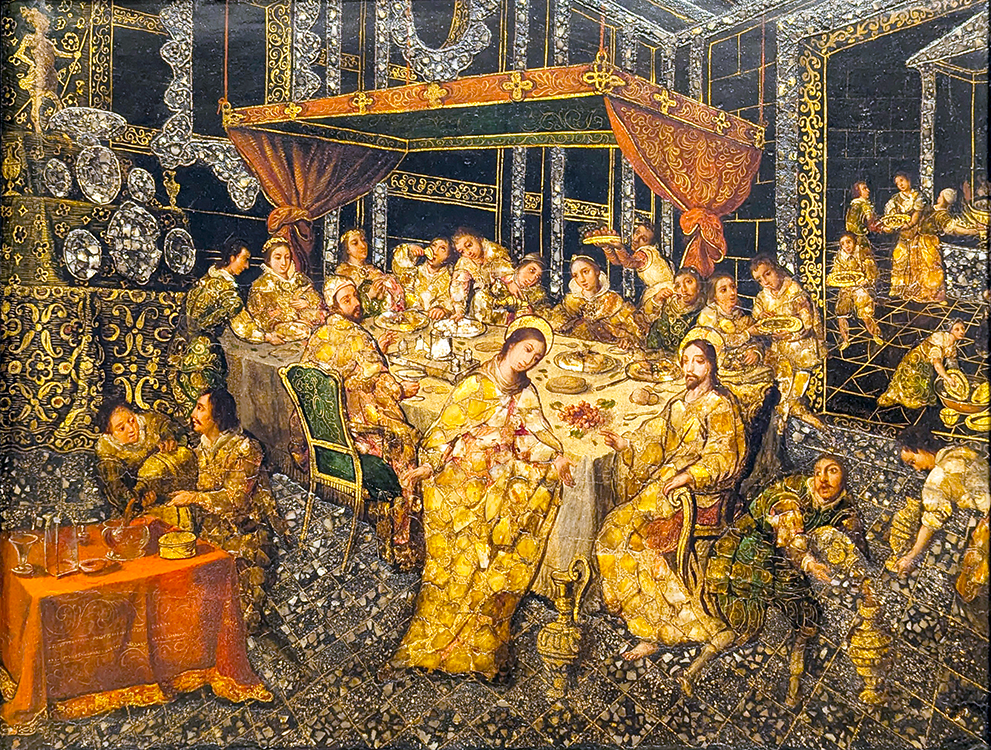

While shells were restricted to the intricate frames above, the art of enconchado extended to depictions of subjects, a technique inspired by Japanese lacquerware and abundant mollusks. Subjects received magical mother-of-pearl cloaks.

Above: “The Wedding at Cana,” Nicolas Correa (1665-aft. 1696), Mexican, oil and mixed media on wood panel inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 1696.

I included the Spanish Zurbaran’s “Santa Lucia” in these photos, as I’m partial to the saint entrusted with protecting what’s left of my vision.

Above left: “Immaculate Conception and Saints,” Manuel Serna, Mexican, oil on copper, circa 1750. “Saint Lucy,” Francisco de Zurbaran (1598-1664), Spanish, oil on canvas, 1640.

The details in Sebastian Munoz’s 1689 memorial painting of Queen Maria Louisa (1662-1689) lying in state were fascinating. Compelled by her father into the arranged marriage at age 17, Maria Louisa obtained her title via a proxy exchange of vows with King Charles II of Spain (1661-1700).

Conspiracy theorists at the time of her death speculated the queen might have been poisoned because she had produced no heir. The fault probably was not hers, as the king’s subsequent wife had no better luck.

During Maria Louisa’s brief reign, Sebastian Munoz became the official painter of the court. In that role, he bore responsibility for painting her lying in state after her death. As per her wishes, the late queen wore the stark attire of a Carmelite nun (Sorry, my photo of the entire piece was marred by glare.).

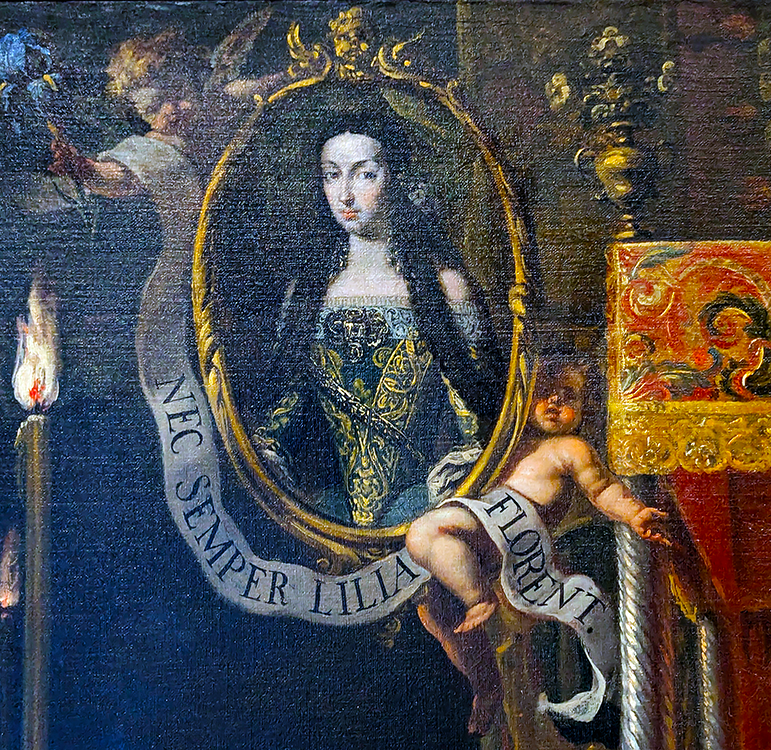

Nec semper lilia florent/The lilies will not bloom forever.”

Banner held by putti in “Marie Louise of Orleans”

Munoz conveyed her regal role by having mourners bearing her crown to the right of the bed. On high, putti support a framed portrait of her in a dress with gold brocade, befitting a queen.

“Above: Details from “Marie Louise of Orleans, Queen of Spain, Lying in State,” Sebastian Munoz, Spanish (1654-1690), oil on canvas, 1689.

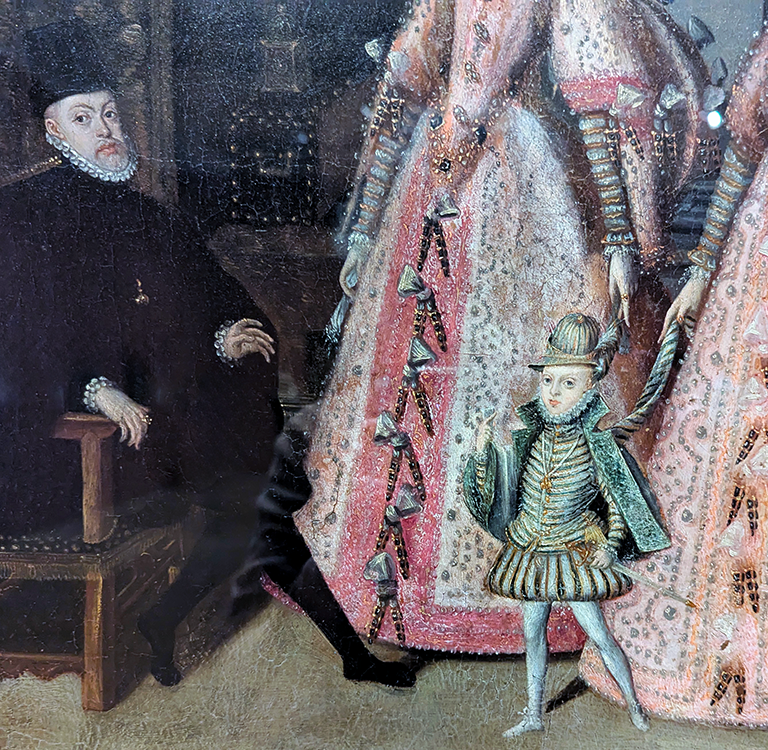

For me, there was something strange afoot in several paintings exhibited. There were the tiny feet of King Philip II (1527-1598) next to his homunculus son, the future Philip III (1578-1621), tethered on a leash by his enormous half-sisters. Perchance the painter retained anonymity because this represented an editorial cartoon? If so, who would have had the nerve at the time to hang it?

Then there’s the devil in the detail of “Saint Michael the Archangel Triumphant over Satan” by Luis Juarez, a Spanish mannerist who moved to Mexico. The devil clearly looks bored instead of intimidated. After all, who would quake with fear by San Miguel wearing hippie-looking flower chanclas? Surely someone must have altered the original 17th-century footwear featured in the painting?

Above right: Detail of “Philip II, King of Spain and His Children,” Anonymous Spanish artist, oil on panel, circa 1581-1584. Right: “Saint Michael the Archangel Triumphant over Satan,” Luis Juarez (1585-1639), Spanish-born relocated to Mexico, oil on canvas, late 1630s.

Running until February 1, the exhibition at the Blanton definitely is worth exploring. Not all paintings have to be masterpieces to provide intriguing insights into art history.