Above: Portion of “The Mountains of Michoacan,” a 2003 mural by Adolfo Mexiac

In the year 1660, Jesuits began construction of Convento de la Compania de Jesus, or the Convent of the Society of Jesus in the city the Spanish called Vallodolid, renamed after the Mexican War of Independence to memorialize native son Jose Maria Morelos (1765-1815). The large rose-colored complex included a temple and a Jesuit college.

Above: Former Templo y Convento de la Compania de Jesus, now a public library and cultural center

Almost a century later, Father Francisco Javier Clavijero (1731-1787) was among the priests assigned to teach there. Born in Veracruz, Clavijero was exposed to parts of Mexico with large concentrations of indigenouse people as his Spanish-born father was transferred to various posts. This instilled strong sympathies in him for the native population of Mexico. His studies in different Jesuit colleges in Mexico were extensive in philosophy, theology, Latin, Greek and numerous other European languages.

While studying at Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City, Clavijero became fascinated with the early documents of Spanish explorers and the Aztec codices in its collections. After his ordination, Clavijero taught at Colegio de San Gregorio, a school for indigenous youths in Mexico City. Scolded by a superior for neglecting his assigned duties to continue his personally preferred studies translating codices, he was transferred away from those distracting resources to teach in Vallodolid.

When King Charles III (1716-1788) expelled Jesuits from all Spanish-speaking territories in 1767, Clavijero wound up in Bologna, Italy. There, he devoted himself to writing a ten-volume history of Mexico from the origins of the ancient kingdom of Anahuac in the Valley of Mexico to the Spanish imprisonment of Cuauhtemoc, the last Aztec emperor, in 1525.

…wealth is easily dissipated by those who have acquired it without fatigue.”

Francisco Javier Clavijero

Unlike many portrayals of the pre-conquest population of Mexico, Clavijero’s Historia Antigua de Mexico described the natives as peaceful and good-hearted. His empathetic portrayal of Aztecs and criticisms of conquistadors were not embraced in Spain; King Charles III should have expelled Clavijero earlier if he wanted to quash such work. His tomes are heralded in Mexico today.

In 1930, the former Society of Jesus Temple was converted into a public library. State offices were established in another portion of the complex, and it was designated the Clavijero Palace.

Murals by four artists were added to the Public Library of Michoacan University in the 1950s. Surprisingly, three were by artists from the United States: Robert Hansen (1924-), who studied under Alfredo Zalce at the Bellas Artes in Mexico City; Hollis Holbrook (1909-1984); and Sheldon Schoneberg (1926-), whose graduate work included a stint at Universidad Michoacana studying frescos in 1952. The sole Mexican artist, Antonio Silva Diaz, is known for his part in designing Morelia’s 1931 landmark fountain, Fuente de las Tarascas. I have absolutely no idea which artist painted the murals pictured below, but the library represents a handsome adaptive reuse.

Above: Biblioteca Publica de la Universidad Michoacan in the former Temple of the Society of Jesus

In 2008, the ex-convento and former school were renovated under the direction of architect Ricardo Legorreta to serve as the home of the Clavijero Cultural Center. The most striking addition to the center is a 2002 mural in a domed stairwell, “Mountains of Michoacan” by Michoacan-born artist Adolfo Mexiac (1927-2019).

Known for art bearing political and social messages, Mexiac is regarded as one of Mexico’s most important graphic artists. In this mural, he endeavored to cover major historical events in Mexico from the Spanish conquest through 2000, including impactful figures from the 18th through 20th centuries.

According to Raul Lopez Teller writing for Elartefacto, the mural was mired in controversy delaying its completion. Perhaps the objections were over the contemporary figures Mexiac chose to include and a panel depicting what many refer to as the Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2, 1968, in Mexico City. An accurate number of the dead, missing and injured during the government’s violent reaction to protesting students has never been determined. Some 5,000 protestors were detained at the time.

Dismissing his detractors as “inquisitors of conservatism,” Mexiac plowed ahead to complete his monumental work.

Above: Portions of “Mountains of Michoacan” by Adolfo Mexiac

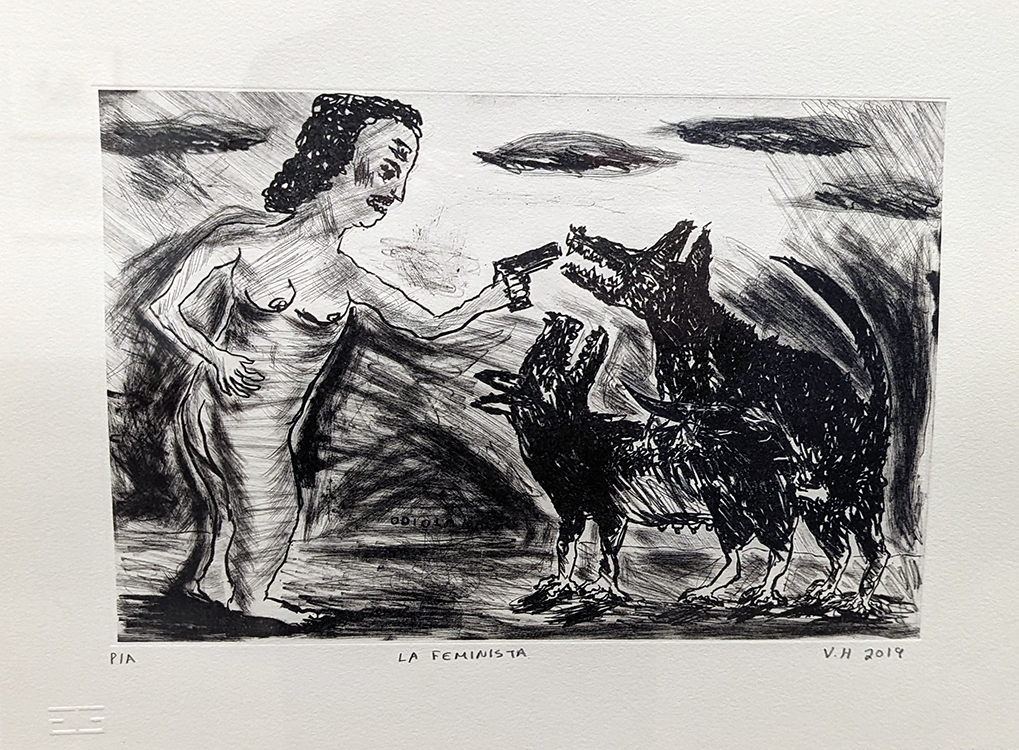

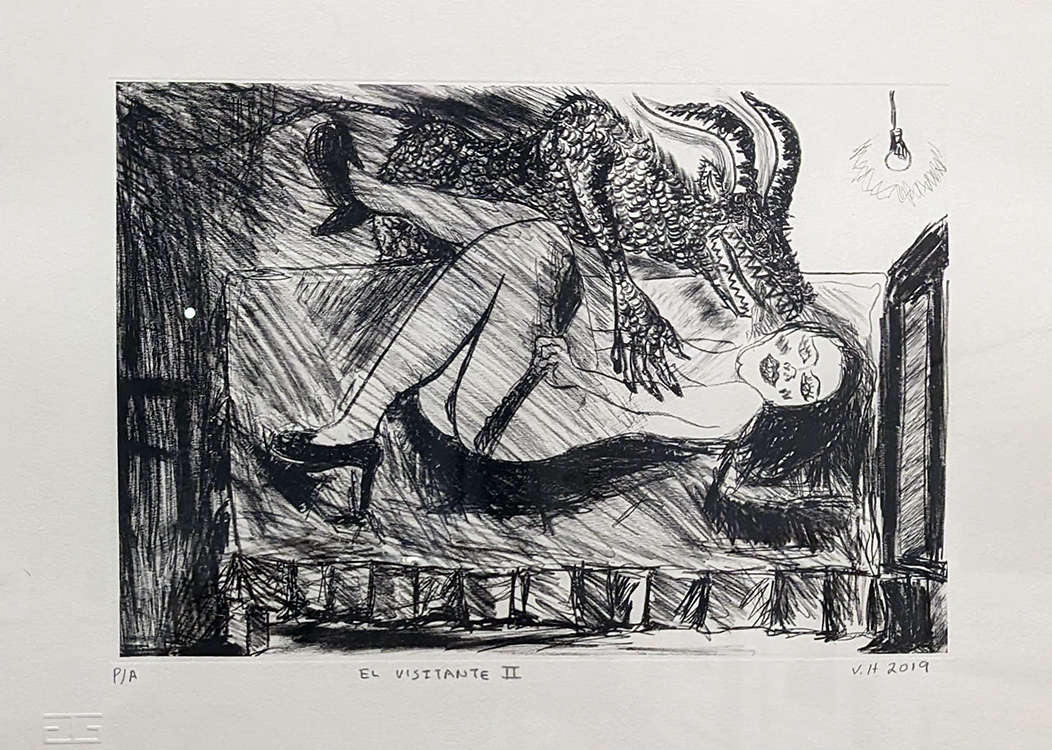

Known for his strong connections with Taller de Grafica Popular, Mexiac probably would have applauded an exhibit hanging in one of the galleries through September 5. “Cinco-Grafias” includes the works of five contemporary Jalisco artists using an evolving technique for printmaking known as siligraphy. The artists employed a wax pencil to draw on aluminum surfaces before coating the non-printing areas of the image with silicone. The exposed areas then were rolled with ink and paper pressed against the drawing.

Above: Siligraphic prints by Victor Hugo Perez

Above: Siligraphic prints by Enrique Oroz

Twenty-three pieces by Michoacan sculptor Maria Angelica Yolanda Gomez Trillo are featured in “The Gaze that Vivifies… The Matter that Flows and Rests,” which remains open until September 18.

Above: Sculpture by Maria Angelica Yolanda Gomez Trillo

Above far right: painting by Jordi Boldo from Barcelona, Spain

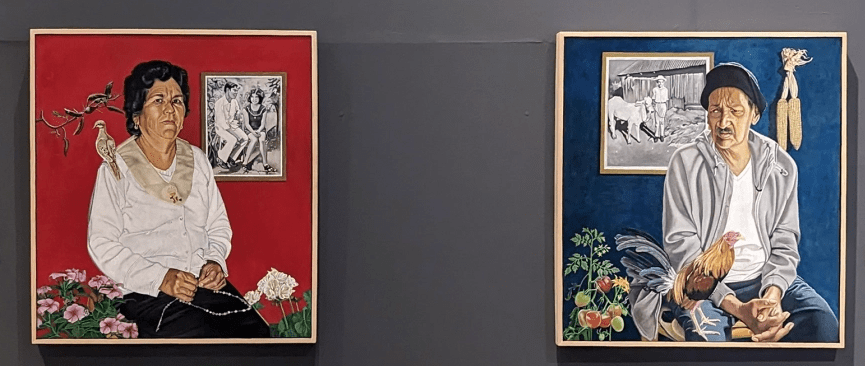

Another Michoacan artist, Santiago Bucio Carrillo, is featured in an exhibition titled “Air, Blood and Earth.” The paired portraits of his parents emphasize their differences. A peaceful dove perched on her shoulder, his mother appears to be piously praying on her rosary for their marriage, while his father looks most concerned about his fighting cock.

Above: Portraits of the artist’s parents by Santiago Bucio Carrillo

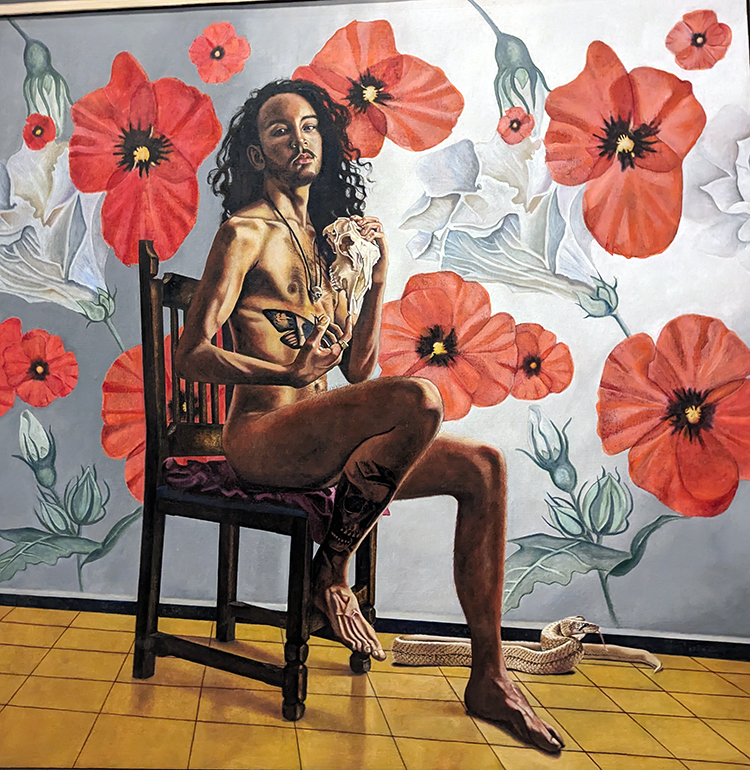

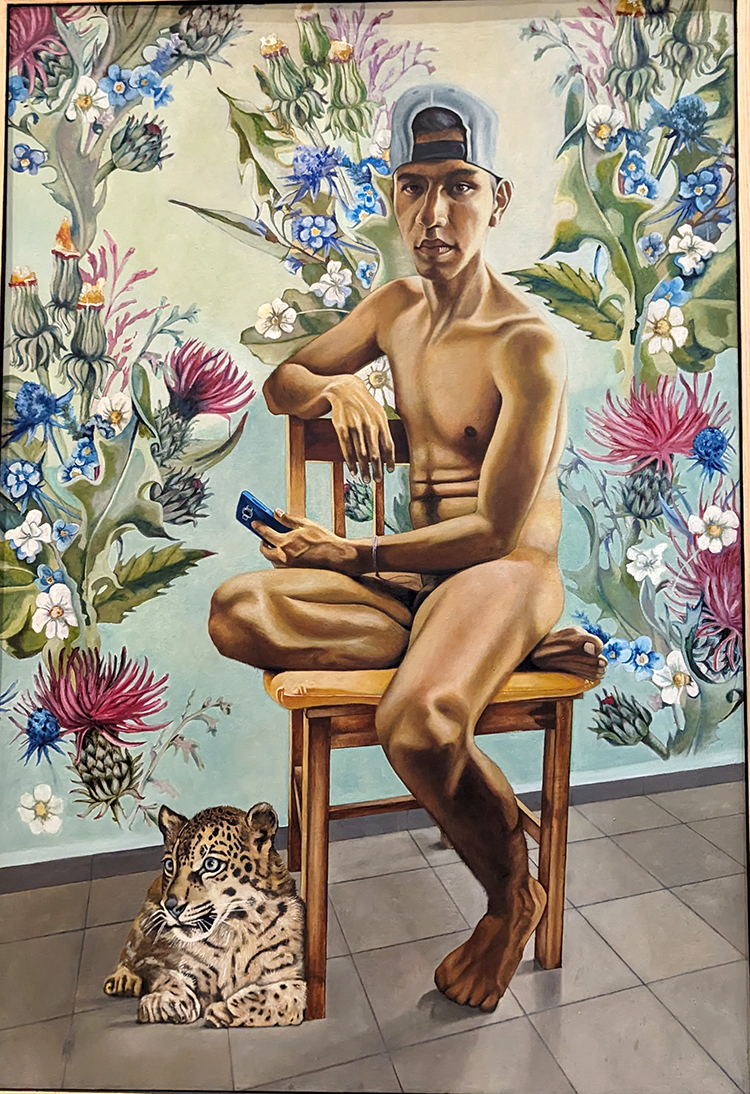

Bucio’s paintings often serve as protests against the societal imposed definitions of masculinity and femininity, blurring those roles. His sensually-posed nudes below are portrayed against florid backgrounds emphasizing femininity contrasted with the dangerous animals resting tamely at their sides.

Above: Part of a series of male nudes by Santiago Bucio Carrillo

While it seems Father Clavijero might nod in approval of the messaging contained in Mexiac’s mural, it’s impossible for me to envision what his reaction would be to the nudes above displayed in the center bearing his name.

Thanks! Good one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Anne. The contemporary art exhibited there was pretty impressive.

LikeLike

Some gre

LikeLike

Wow! It’s almost as if I’d been there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Felt as though you climbed each and every one of those steps up to see the mural, huh?

LikeLike