Above: Caves created by ancient Greek quarries, including the notorious Ear of Dionysius, line a bluff in the Archaeological Park of Neapolis

Long ago, Siracusa became an important outpost of the Grecian Empire. For strategic reasons, the ancient city first developed on the small island of Ortigia.

A major vestige of this are the ruins of the Temple of Apollo in the heart of the city adjacent to the island’s bustling outdoor market. Forty-two monolithic columns once framed the sixth-century-BC Doric temple dedicated to the sun god. These remnants of the temple incorporated into several private homes and 16th-century military barracks occupying the site were “rediscovered” in the 1890s.

Ruins of the sixth-century-BC Temple of Apollo

Under the tyrant Gelon (?-478 BC), Siracusa grew in size to rival Athens. Upon seizing power over the city in 485 B.C., Gelon enslaved much of the population. He imported riches in an unusual method, by forcing wealthy aristocrats from other cities he ruled in Sicily to relocate to his new capital.

To protect and expand his domain, Gelon built an army of more than 50,000. Joining with another ally in Sicily, his military strategies were credited with inflicting casualties on 150,000 men at the Battle of Himera. This victory successfully expelled the Carthaginians from Sicily, not permanently however, with the resulting peace treaty netting payment of 2,000 talents (more than 100,000 pounds) of silver for the victors. The decisive win, and the silver with which Gelon returned, enhanced his popularity in Ortigia.

A later tyrant, Dionysius I (432-367 BC), came to power in Siracusa with a force of hired mercenaries. He used his men to consolidate an iron grip over the city. The former clerk, turned soldier, prided himself on his writing talents, penning epic poems and plays. He surrounded himself with Greek poets and philosophers, including Plato (about 424-347 BC).

Recognition of Siracusa as a cultural center was important to Dionysius, so he commissioned one of the largest theaters in the Greek world and had it built outside the existing fortified walls with a sweeping panoramic view of Ortigia.

The Archaeological Park of Neapolis and views of modern Siracusa down below and the island of Ortigia in the distance

The view from the top of the theater to the sea makes a spectacular backdrop for plays, and certainly a tragedy or two of Dionysius were among those performed. The sad news was that we could not see the ancient stone seating forming a semicircle around the stage. It was covered with protective plywood bleachers on which scurrying workers were putting the finishing touches. This marred the affect of visiting the archaeological site completely, and we couldn’t even bear to take a photo of it.

The good news is that the theatre actually is used. The temporary seating we saw is reinstalled every summer for its original purpose – live performances of ancient Greek plays. So, I’m sharing a more handsome image of it it below.

Sicilians build things like they will live forever and eat like they will die tomorrow.”

– Plato

We are not sure whether Dionysius was his given or chosen name. Perhaps similarity to the name of the Greek god Dionysus was no mere coincidence. A son of Zeus, Dionysus was the god of wine, fertility, festivity, ritual madness and theater, among other things. The court of the tyrant Dionysius elevated debauchery to an art, an art disparaged by Plato.

According to Nick Romeo and Ian Tewksbury in “Plato in Sicily,” an essay published online by Aeon, Plato was about the age of 40 when he first visited Siracusa. The decadent court was where he sought:

…to test his theory that if kings could be made into philosophers… then justice and happiness could flourish at last.

…Plato’s conviction soon collided with the realities of life in Sicily. The court at Syracuse was rife with suspicion, violence and hedonism. Obsessed with the idea of his own assassination, Dionysius I… would force visitors – even his son Dionysius II… – to prove that they were unarmed by having them stripped naked, inspected and made to change clothes….

Plato angered Dionysius I with this philosophical critique of the lavish hedonism of Syracusan court life, arguing that, instead of orgies and wine, one needed justice and moderation to produce true happiness. However sumptuous the life of a tyrant might be, if it was dominated by insatiable grasping after sensual pleasures, he remained a slave to his passions….

The response of Dionysius I was to sell Plato into slavery. Demonstrating the importance of maintaining strong platonic relationships, the philosopher’s friends chipped in to raise ransom to free him. Plato was far luckier than many a man who crossed Dionysius, known for summarily executing those who made him feel the least bit threatened. Dionysius kept the prison he established in one of the old quarries full of captured soldiers and perceived enemies.

This cavernous space has been nicknamed the Ear of Dionysius because of its internal shape and because, standing at a particular spot above, it was possible to eavesdrop on prisoners’ softest whispers. That spot is off limits now, but that doesn’t stop schoolchildren on field trips from testing the volume by screaming, sending echoes resounding throughout the park.

Some say Dionysius I went out in Dionysus style, drinking himself to death in celebration of one of his tragedies winning a prize in Athens. Others believe he was poisoned by the son impatient to succeed him. Maybe the father’s paranoia was justified after all.

The archaeological site also contains the base of what once was an enormous sacrificial altar built by King Hiero II (308-215 BC). More than 400 bulls were slaughtered during a ceremony to honor Zeus for helping liberate Siracusa from an earlier tyrant.

While Dionysius I employed his theater for cultural purposes, a later massive amphitheater constructed nearby by Romans was used for violent spectacles, such as gladiators’ fierce battles-to-the-death. The stony footprint of this and a few of its lower chambers can be explored.

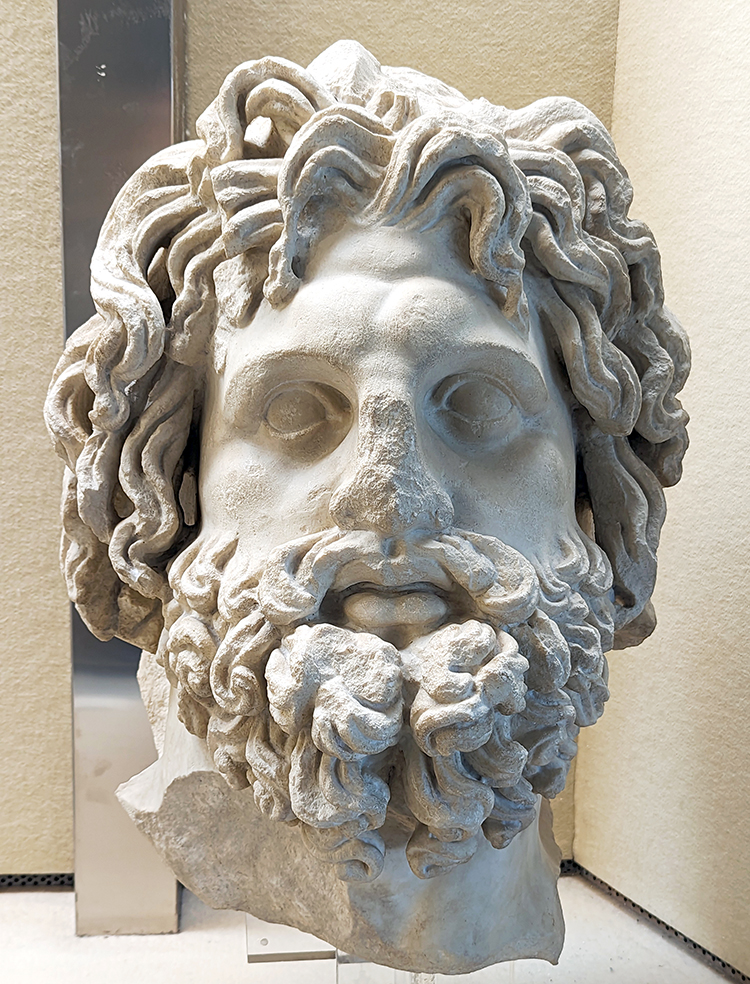

If, like me, chunks of quarried stone fail to paint the whole picture for you, artistic adornments popular during the Greek and Roman periods are preserved in the Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum. Many of the sculptural human figures suffered severance from some of their limbs during the intervening centuries.

Above: Archaelogical artifacts in the Paolo Orsi Archaeological Museum

In the spirit of the ancients, I found myself needing to be wined and dined on the walk between the park and museum. We felt fortunate to stumble across Olivia Natural Bistrot, packed with professionals who work in the more suburban area, none of whom appeared to miss meat or seafood. I enjoyed a luscious beet risotto, while the Mister ordered the extremely popular “veg burger,” a satisfying combination of eggplant, lentils and millet.

The surprising contorni offering was cabbage, surprising in that I ordered it. I don’t normally care for cooked green cabbage, neither its taste nor smell. But Olivia’s was braised until caramelized and crowned with pine nuts, caraway seeds and wild fennel – wonderful. If this restaurant weren’t so remote from where we were staying, we definitely would have headed there again.

Above: Lunch at Olivia Natural Bistrot

Thanks for that. It is good to have the historical background. I read Thucydides.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thucydides? Oh, dear. Not sure you will be able to stomach some of the loose interpretations of history in the posts that lie ahead. Please feel free to comment to offer readers a more accurate telling.

LikeLike