Above: Monument commemorating a hometown hero, Archimedes

Certain things first became clear to me by a mechanical method, although they had to be demonstrated by geometry afterwards because their investigation by the said method did not furnish an actual demonstration. But it is of course easier, when we have previously acquired by the method, some knowledge of the questions, to supply the proof than it is to find it without any previous knowledge.”

Archimedes (About 287-211 BC)

Seriously? The above is an example of Archimedes-speak that is babble to me. Math is far from one of my languages – Greek to me. In fact, I would almost consider Archimedes an enemy – the Father of Mathematical Physics, the Father of Integral Calculus and the man who tortured himself long enough to figure out such seemingly unsolvable puzzles as Pi.

Except, a visit to Siracusa convinced me that in times of war, or peace, you definitely would want Archimedes with all his math and inventions on your side.

The ancient heart of Siracusa is Ortigia, which as an island appears as though it would be difficult to conquer. Involved in constant conflicts with the Carthaginians occupying the other side of Sicily, Dionysius I (432-367 BC) built an enormous fortress on the island and built more than 13 miles of walls to protect much of the sprawling city. I’m not sure how high those walls were, but even the sea walls of today, fronted by huge boulders in many places, look formidable for approaching ships.

Above: Seawalls surrounding Ortigia

History, though, has proven numerous times that the walls were not impregnable. But, we’ll skip ahead to the rule of Hiero II (308-215 BC). With Roman forces increasing in power, Hiero found himself compelled to sign a treaty with Rome in 263 BC. Aside from periodically sending troops to assist Romans during the Punic War, this treaty led to 50 years of relative peace for Siracusa.

Give me a place to stand, and a lever long enough, and I will move the world.”

Archimedes

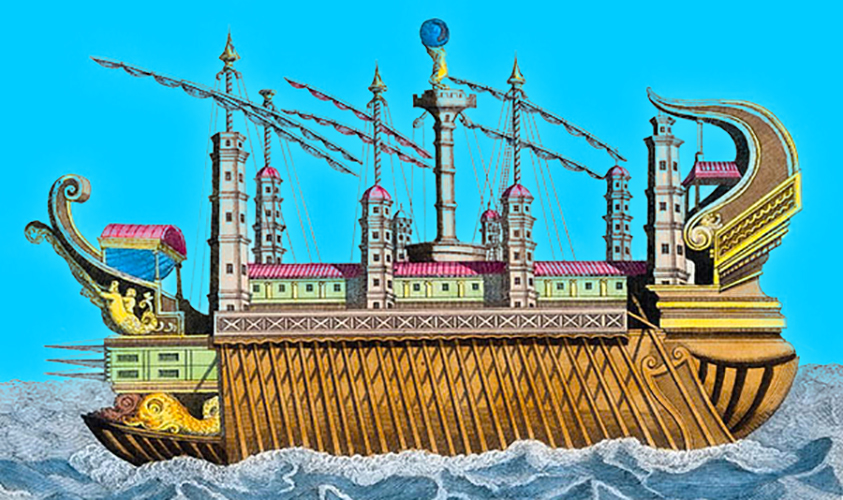

Archimedes was fortunate to be born during this period. He was able to pursue all types of mathematical theories and inventions. And Hiero was smart enough to enlist Archimedes for projects useful to the preservation of the fiefdom. What became known as Archimedes screw for moving water from a lower to an upper level helped him engineer the construction of the largest ship of its time by reducing potential danger created by water leaking through the hull.

Archimedes’ invention of a water pump, known as the Archimedes screw, enabled him to design an enormous ship, “Siracusa,” for Hiero.

Eureka!”

Legend has it that Archimedes was so nerdy that, in excitement upon realizing the value of water displacement as a measurement tool as he sank into his tub, he leapt out and ran naked through the streets shouting “Eureka.” While I soaked in the tub today mulling that over, it seemed that particular theory occurred to me in kindergarten. Archimedes might have figured out how to put that knowledge to practical use, but it’s hardly his most amazing discovery and certainly not one that should have made him forget his clothes. And, while he’s credited with coining the expression, it translates from ancient Greek to “I found it,” hardly a phrase unique to the inventor.

As unlikely as it seems, if Archimedes was a street-streaker, Hiero presumably would not have cared. He harnessed the inventor’s brainpower for the development of defensive weapons for Siracusa. Although not needed during his reign, a large number of this next era of weaponry was stockpiled.

The heir in line to rule was Hiero’s 15-year-old grandson, Hieronymus (231-214 BC), probably a bit too young to take on the job. In its earlier days, Siracusa was in the middle of a constant tug of war between Carthaginians and the Greeks. Now the Romans had replaced the Greeks in the same power play. Two of the young king’s uncles persuaded him to court Hannibal (247-183 BC) in Carthage instead of remaining loyal to Rome. The Roman faction was not pleased, and, after a little more than a year in power, Hieronymus was assassinated.

A leadership crisis ensued, with the Carthage-leaning group coming out on top. In the midst of the Second Punic War with Carthage, Rome’s anger increased. Marcus Claudius Marcellus (270-208 BC) was sent to quickly dispatch the rebellious residents of Siracusa. It should only take a few days for the Romans to conquer Siracusa, right? Kind of like Russian forces in the Ukraine.

While Archimedes might not have been in favor of the path chosen by the rulers, he was loyal to Siracusa. Plus, Marcellus’ reputation preceded him. After his recent conquest of Leontini, Sicily, the commander had his men behead more than 2,000 captured within the city walls. So Archimedes applied all his wit to hold the vengeful Roman invaders at bay.

On his extensive website devoted to Archimedes, Chris Rorres includes excerpts of a translation of an account of the siege by Polybius (about 200-118 BC):

Marcellus was attacking… from the sea with sixty quinqueremes (a galley with three banks of oars), each vessel being filled with archers, slingers and javelin-throwers, whose task was to drive the defenders from the battlements….

But Archimedes had constructed artillery which could cover a whole variety of ranges, so that while the attacking ships were still at a distance he scored so many hits with his catapults and stone-throwers that he was able to cause them severe damage and harass their approach. Then, as the distance decreased and these weapons began to carry over the enemy’s heads, he resorted to smaller and smaller machines, and so demoralized the Romans that their advance was brought to a standstill. In the end Marcellus was reduced in despair to bringing up his ships secretly under cover of darkness.

But when they had almost reached the shore, and were therefore too close to be struck by the catapults, Archimedes had devised yet another weapon to repel the marines, who were fighting from the decks. He had had the walls pierced with large numbers of loopholes at the height of a man, which were about a palm’s breadth wide at the outer surface of the walls. Behind each of these and inside the walls were stationed archers with rows of so-called “scorpions,” a small catapult which discharged iron darts, and by shooting through these embrasures they put many of the marines out of action.

While not recorded by Polybius, legend and the monument pictured at the top of this post credit Archimedes with employing a series of parabolic mirrors to reflect and intensify the sun’s rays, concentrating them into a powerful weapon setting Roman galleys ablaze. But Polybius does recount additional contributions of Archimedes:

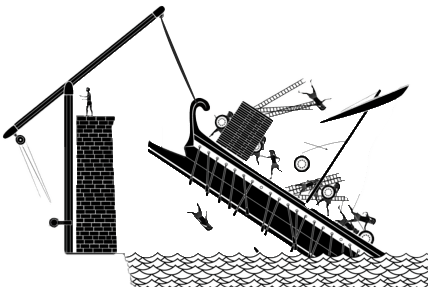

Other machines invented by Archimedes were directed against the assault parties as they advanced under the shelter of screens which protected them against the missiles shot through the walls. Against these attackers the machines could discharge stones heavy enough to drive back the marines from the bows of the ships; at the same time a grappling-iron attached to a chain would be let down, and with this the man controlling the beam would clutch at the ship. As soon as the prow was securely gripped, the lever of the machine inside the wall would be pressed down.

When the operator had lifted up the ship’s prow in this way and made her stand on her stern, he made fast the lower parts of the machine, so that they would not move, and finally by means of a rope and pulley suddenly slackened the grappling-iron and the chain. The result was that some of the vessels heeled over and fell on the sides, and others capsized, while the majority when their bows were let fall from a height plunged under water and filled, and thus threw all into confusion.

Blockading Siracusa seemed easier to the frustrated Romans than the risk of encountering more from Archimedes’ bag of tricks. But the island of Ortigia was blessed with a supply of freshwater, the Fountain Arethusa, believed by the ancient Greeks to be the spot where the nymph Arethusa emerged after escaping the unwanted attention of the god Alpheus. Now filled with papyrus and ducks, the water supply helped the island ward off the Romans for close to two years.

Marcellus finally was able to take advantage of the islanders’ celebration in honor of Artemis, a virgin goddess who, as a protector of other virgins, had rescued the nymph Arethusa. Unfortunately, the life-giving spring contributed to Ortigia’s fall. There was a stairway from the sea up to the fountain, and, amidst the distractions of the religious festival, men under Marcellus were able to sneak up and breach the walls.

The traditional reward for victorious troops was the right to pillage, but, before releasing his men to do so, Marcellus ordered for Archimedes to be brought to him unharmed. Rorres’ website includes a version of what occurred as recorded by first-century historian Valerius Maximus:

At the capture of Syracuse Marcellus had been aware that his victory had been held up much and long by Archimedes’ machines. However, pleased with the man’s exceptional skill, he gave out that his life was to be spared, putting almost as much glory in saving Archimedes as in crushing Syracuse.

But as Archimedes was drawing diagrams with mind and eyes fixed on the ground, a soldier who had broken into the house in quest of loot with sword drawn over his head asked him who he was. Too much absorbed in tracking down his objective, Archimedes could not give his name but said, protecting the dust with his hands, “I beg you, don’t disturb this,” and was slaughtered as neglectful of the victor’s command; with his blood he confused the lines of his art.

Don’t disturb my circles.”

Dying words of Archimedes, according to oft-repeated lore

I like to think Archimedes uttered a regret, like “Why Pi?” Or perhaps a curse on the conquerors, “Make them learn Pi.”

Handsome working models of inventions of two geniuses, Archimedes and Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), encourage hands-on operation in the Archimedes and Leonardo Museum. Driven inside by showers, we dropped into the museum on what turned out to be a holiday. It was serving its educational purpose, filled with families and kids darting about between exhibits.

I felt this math-challenged visitor could have learned a lot, but, with exhibits crowded together, I would have had to shove children aside to approach. It seems a worthwhile place to explore, but pick your day more carefully than we did.