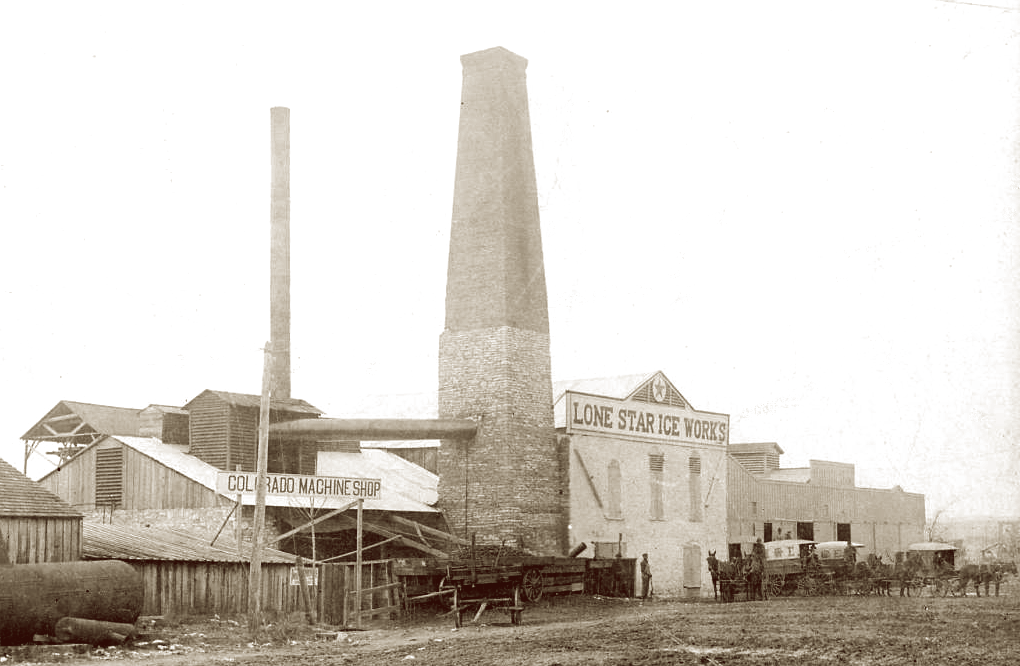

Above: Lone Star Ice Works, George H. Berner and H.R. Marks, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Portal to Texas History

The loss in this climate is enormous and it is probably within bounds to say that at least one sixth of the gross output melts away. The manufacture of tons of ice and its delivery to customers at a cent a pound is one of the novelties of this age, and had you ever hinted such a thing 30 years ago you would have been looked upon as insane.

Austin Statesman, July 17, 1890

Born in 1858 on the banks of the Ohio River in Indiana, Andrew Jackson Zilker started working riverside as a stevedore and cabin boy while young. He stumbled across a copy of Henderson Yoakum’s extensive History of Texas, published in 1846, and began dreaming of Texas. He worked his way via riverboat to New Orleans; earned his way to Texas by driving oxcarts to San Antonio; and arrived in Austin at age 18.

The 50 cents in his pocket, according to numerous accounts, was quickly depleted – half for a bed on the first night and the other half for food. Hunger motivated him to land employment helping to construct the International-Great Northern freight depot and then the Congress Avenue Bridge over the Colorado.

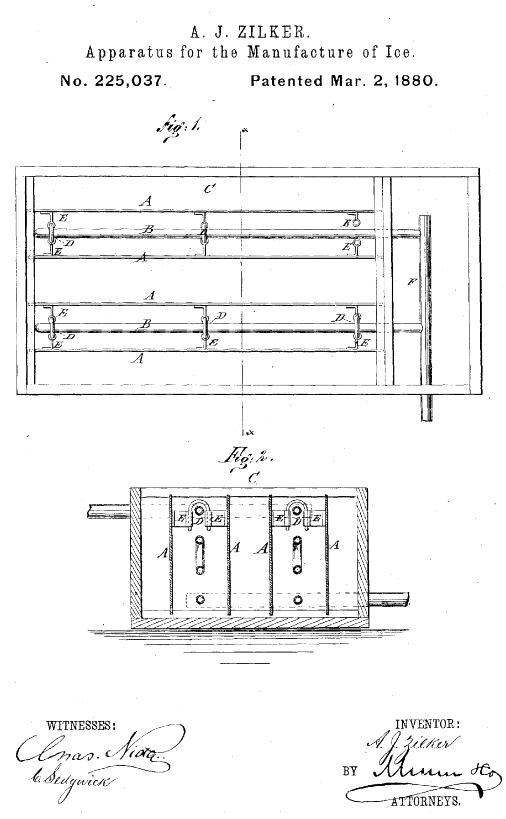

Curiosity led Zilker to investigate how artificial ice, a particularly appealing life enhancement for Texans, was made. His interest helped him secure a job at the ice plant on Colorado Street. He quickly was promoted to foreman and engineer, securing patents for machines to assist in the manufacture of ice as early as 1880.

Backed by investment dollars provided by John Thomas Brackenridge (the brother of prominent San Antonian George Brackenridge and an extremely beneficial connection for Zilker), Zilker soon was managing the plant and in 1885 changed its name to Lone Star Ice Works. The 1894 Industrial Advantages of Austin reported the plant covered half a block on the riverfront, with two ice machines – one with 15-ton capacity and the other with 25. Using distilled water, Lone Star was capable of producing 80,000 pounds of ice daily, more than the market needed.

According to a 2013 article in the Austin Chronicle, there were many in Austin who believed manmade ice inferior to nature’s own. To win them over as customers, Zilker lined chunks of lake ice* on one side of Congress Avenue and that of Lone Star Ice Works on the other. Gathered spectators were amazed that the lake ice disappeared into puddles long before Zilker’s.

(*We have to take a quick break here for an aside. Until research for another project a couple of months ago, I would have slammed on the brakes here. Lake ice in Austin? [Well, ignore recent freak weather that made that a reality.] Maybe this concept didn’t strike you as novel, but I had never thought about ice arriving in Texas. Essentially I assumed there was none in the early days of the republic and state. But Charles Hayes 1870 book, Galveston, altered my erroneous thinking: The British Consul in Galveston as early as the spring of 1839 reported that “a brig arrived from Boston, a voyage of 3,000 miles, with 150 tons of ice, to cool the beverages of the citizens, and otherwise minister to their comfort.” Ice was “imported” from the north.)

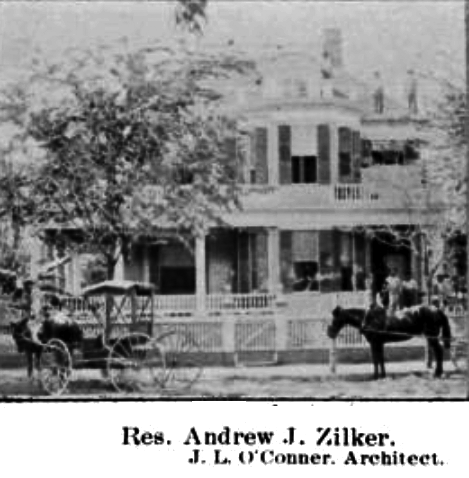

Soon, Ida and Andy Zilker were able to commission a two-story house on the corner of Second and San Jacinto. Zilker’s interests included a brickyard, and he filed patents for several inventions to speed the drying and transportation process for bricks. Membership in the Austin Lodge of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks enhanced his business connections in the community, but perhaps the most valuable boost in prestige was provided by his association with John Brackenridge, president of First National Bank, where Zilker became a director. Zilker’s holdings expanded to ice plants, water companies, and coal and milling operations in places such as Taylor and Llano. He later became Austin’s first bottler of Coca-Cola. Zilker served several terms as a city alderman and began serving on the school board.

But all of this background for me, as a newcomer to Austin, is to get us to the property he purchased in 1901. This property included 350 acres surrounding Barton Springs (other newcomers might want to visit the prior post about Billy Barton). This gave Zilker access to the purest source of water around, and the acreage served as grazing space for the horses and mules used to haul the wagons delivering ice to customers. Zilker soon built an amphitheater and a concrete pool for his fellow Elk members to gather.

He and Ida planned to build a new house there overlooking the springs and downtown. But in April of 1916 while riding with the family in their automobile, Ida suffered a fatal “apoplectic stroke.” After that, Zilker lost his enthusiasm for relocating to Barton Springs.

Zilker was head of the school board at the time and saw a great need for cultivating more than knowledge in the classics. He felt students needed practical skills: home economics for girls and industrial training for careers for boys. In 1917, possibly inspired by his friend, George Brackenridge of San Antonio, he deeded acreage around the springs to the Free Public Schools of Austin to sell to the city for a public park. Over the next ten years, the city paid the school district a total of $100,000 for an endowment funding the teaching of those practical skills, the Zilker Permanent Fund. Numerous subsequent gifts were made between then and 1934.

In 1924, a bathing pavilion was built by the springs, and four years later the pool was improved by the construction of a permanent dam. In the 1930s, attractions included the municipal horse stables, a skeet-shooting range and the Texas Reptile Institute. Camp houses were added to accommodate Boy and Girl Scouts.

When accepting a “Most Worthy Citizen” Award in 1927, Zilker referred to Barton Springs as a sacred spot, one dedicated to the memories of Robert E. Lee and Albert Sidney Johnson. That dedication to Confederate generals has been cast aside, with Zilker being remembered instead for his generosity and wisdom in recognizing that such an incredibly beautiful spot should not belong to one individual but to all the people of Austin.

When Andrew Jackson Zilker died in 1934, flags on state buildings fluttered at half-mast.

Note Added on November 21, 2021: SanAntonioRiverWalker posted an ideal companion piece about an early icemaker. Click here.