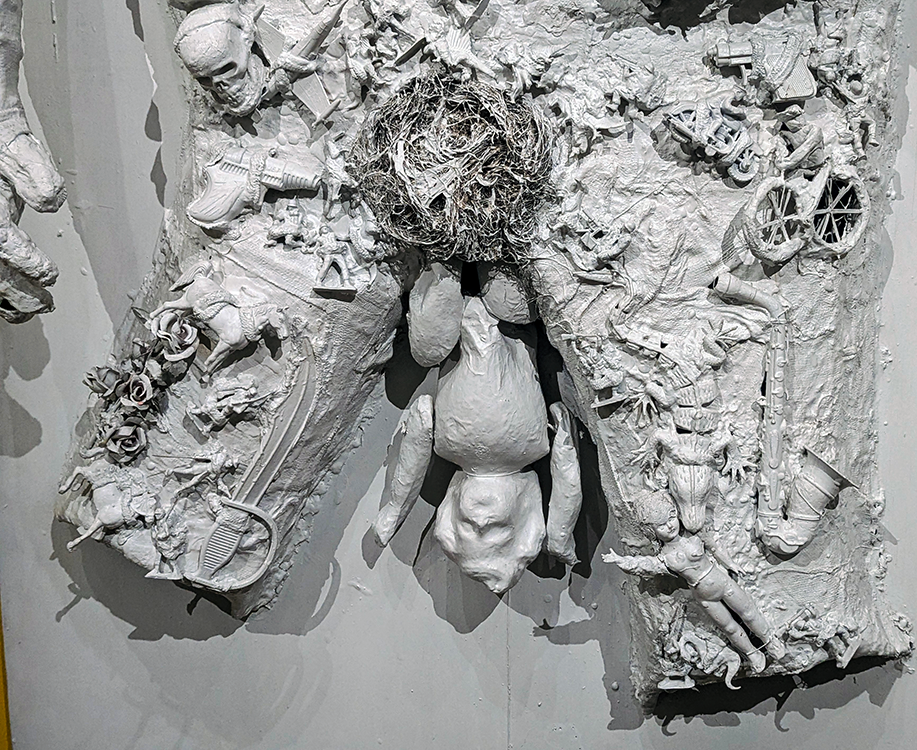

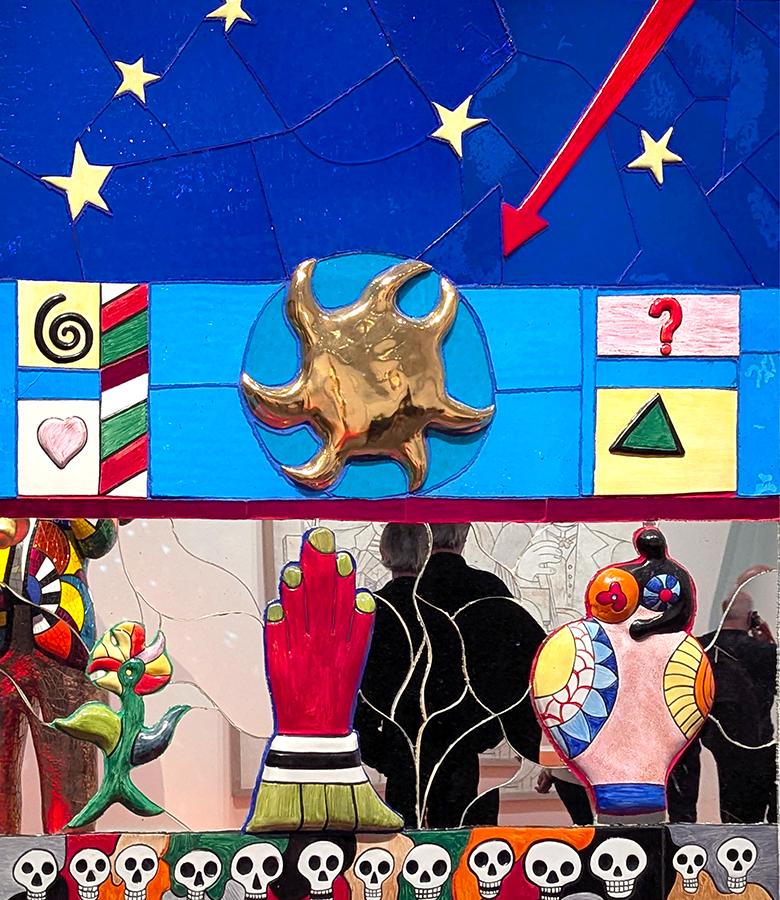

Above: Detail of “Monster Crocodile,” a 1964 assemblage by Niki de Saint Phalle.

I wanted [the fountain] to have charm, with the colors of Niki…. I wanted sculptures like street performers, a little bit like a circus, which was at the heart of Stravinsky’s style itself when in 1914 he had his first encounter with jazz….”

Jean Tinguely (1925-1991)

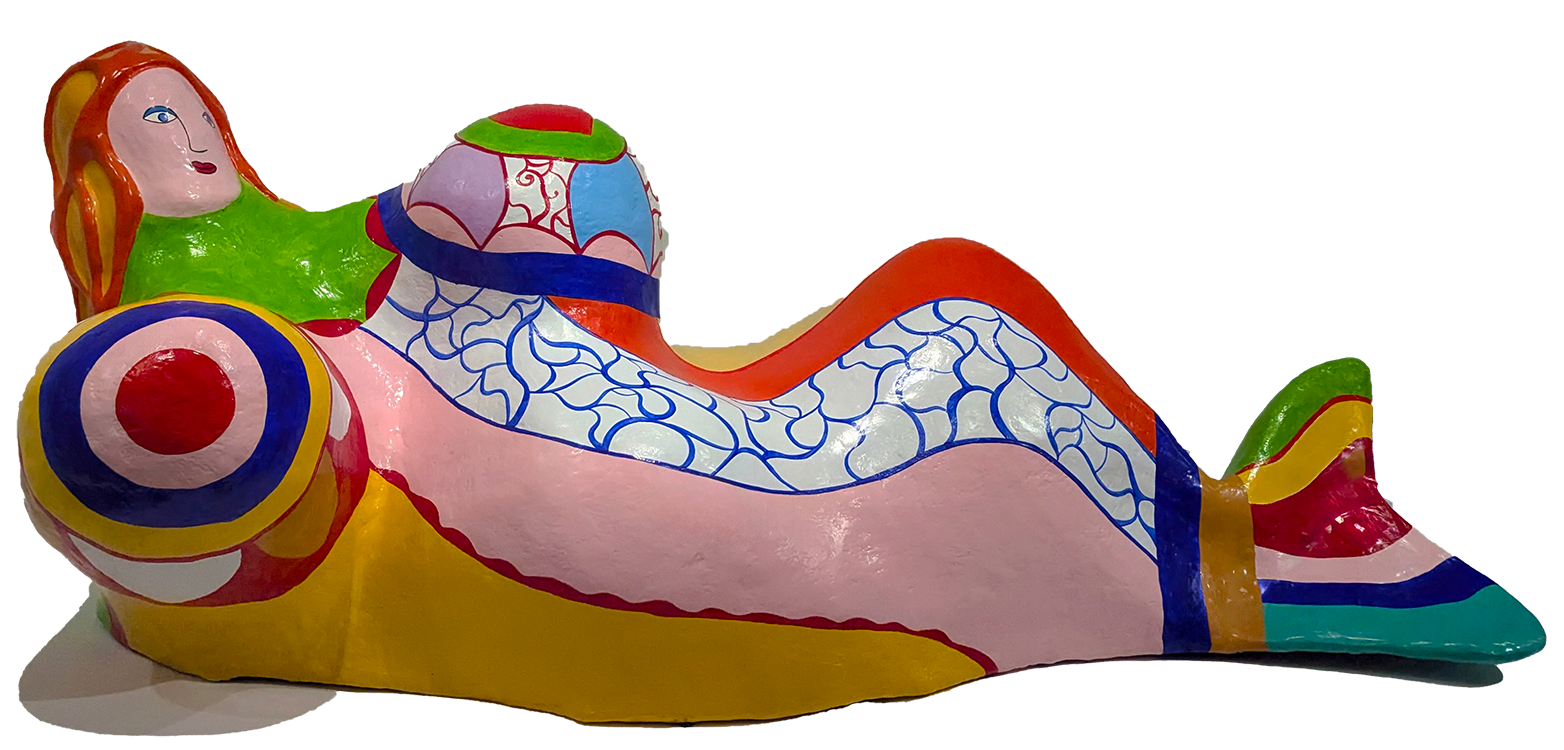

With bright primary colors twirling around squirting water in all different directions, the 1983 “Stravinsky Fountain” by Niki de Saint Phalle and husband Jean Tinguely ignited a public space between the Pompidou Center, housing the National Museum of Modern Art, and the Gothic-style Church of Saint-Merri. Viewing the flamboyant fountain evokes a childlike joyful feeling in even the most jaded adults.

Above: “Stravinsky Fountain,” Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, Paris, France, 1983.

That whimsical, playful exuberance bubbling up in the fountain and her jubilant plump “Nanas,” with figures resembling my own, meant I failed to take a serious look at her art. I must have been in a teenage trance to miss the media coverage when she exhibited a giant Nana “Hon” with an entryway for attendees between her widespread legs.

Underestimating Saint Phalle’s talents for decades was a mistake. An exhibition this spring at the Caumont Center for Art in Aix-en-Provence altered my misconceptions.

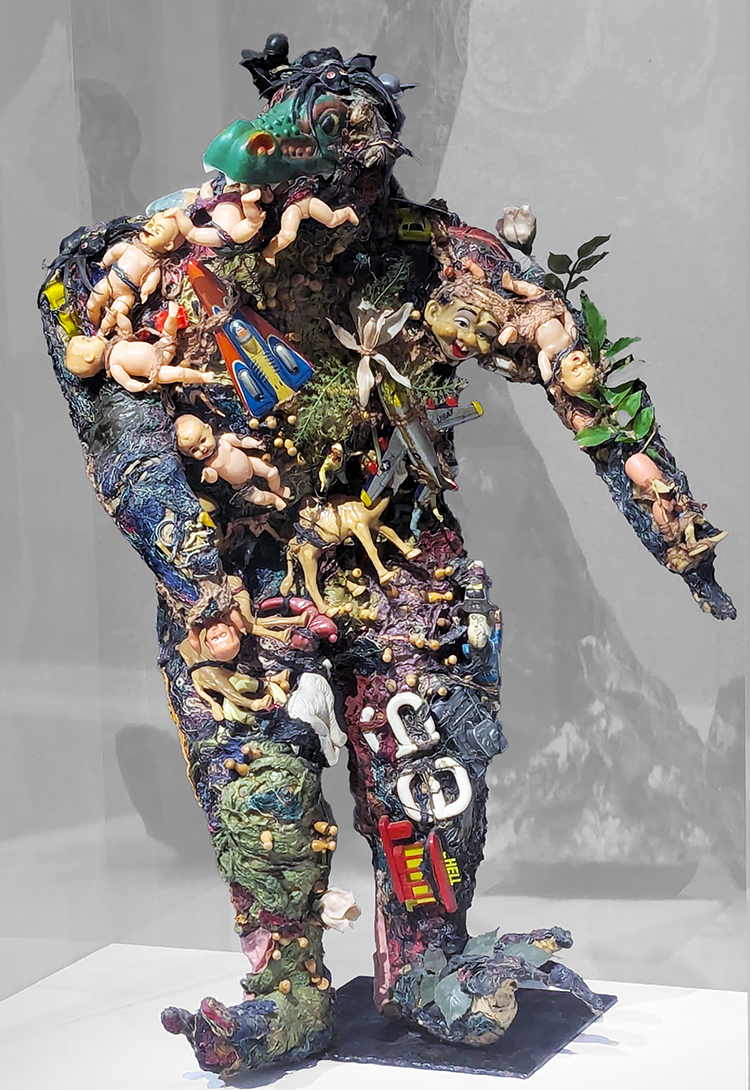

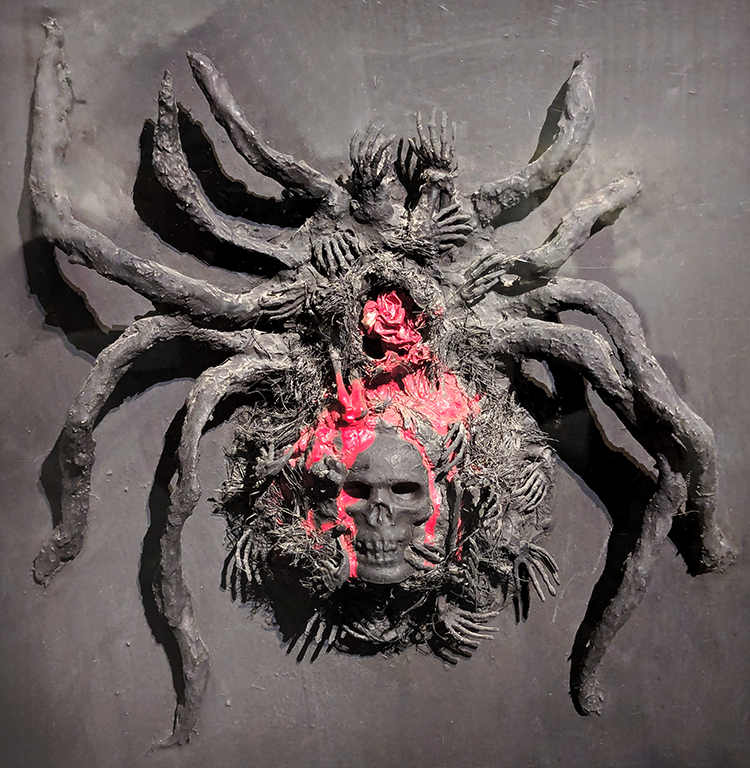

Taming her inner dragons is precisely the process Niki de Saint Phalle implemented in her art as she searched for a way to assuage her anxieties. ‘Painting calmed the chaos stirring in my soul. It was a way of taming the dragons that were forever surging forth in my work.'”

Curator notes at the Caumont Art Center

Saint Phalle was plagued by anxiety and while still young suffered a nervous breakdown. Dragons and monsters were ever-present in her early works. She was quick to admit motherhood was not her forte.

As with some figures, Saint Phalle’s mother devoured her, and the artist admits to having in turn devoured her children.”

Curator notes at the Caumont Art Center

Saint Phalle was an ardent feminist. Her Nanas reflected a rejection of demands on women to attain perfect Barbie-like figures. She considered the expectations of marriage, childbirth and motherhood as smothering women’s energy and talents.

Above: Images from a 2025 exhibition focused on the art of Niki de Saint Phalle at the Caumont Art Center in Aix-en-Provence.

Saint Phalle was appalled by the racism she witnessed in America. Sculptures of a biracial couple in bed and Black heroes were among her weapons to fight prejudice.

Top left: A Nana in a gallery window in Paris. Other images from “Tous Leger!” exhibition, Musee du Luxembourg, Paris, 2025. “Miles Davis” is juxtaposed with an example of influential work by Fernand Leger (1881-1955).

Saint Phalle was an advocate for confronting global climate change. And AIDs awareness was a personal campaign for her. Two friends she held particularly close died of the disease, and she memorialized them with sculptures installed at their graves in Cimetiere Montparnasse in Paris.

To my friend Jean-Jacques who flew away too early.”

Niki de Saint Phalle on 1992 memorial for a friend buried in Cimetiere Montparnasse

Above: Graveside memorials created by Niki de Saint Phalle for friends who died of AIDs. Cimetiere Montparnasse, Paris.

Saint Phalle’s exuberant method of coping with her personal depression and feelings of loss via these memorials helps others through their grieving processes.

What talent – teaching us to confront and overcome demons by taming them with color. Wish I’d had access to Saint Phalle’s art at age six to help battle the terrifying monsters in my closet and crocodiles lurking under my bed.