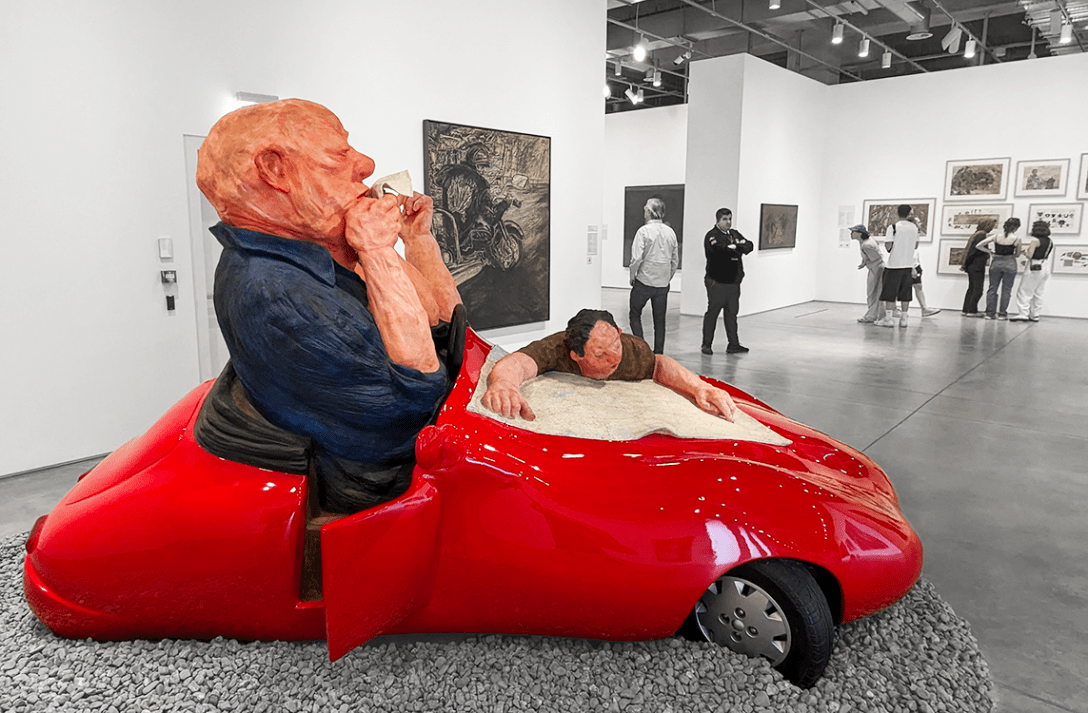

Above: “Racing Car,” Mehmet Guleryuz, 2017, Istanbul Museum of Modern Art

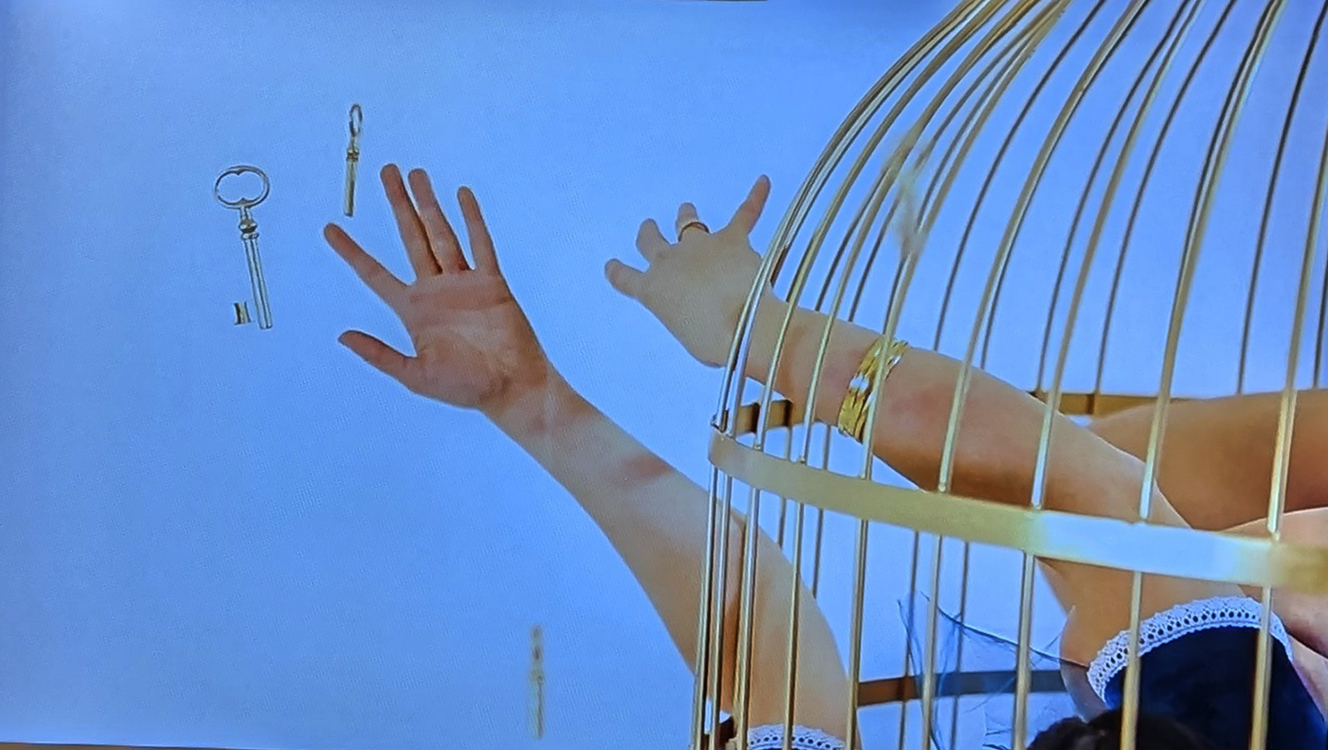

But I’m not going for realism…. I’m not going to paint his cage. Lemon will be perched in front of the window like a wild bird who has alighted there of his own free will.”

The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk, 2009

Birdcages. Potent symbols. Ever since visiting Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence in Istanbul on this same trip, it seems I have been seeing birdcages incorporated in artworks everywhere I go. Often with human figures inside – women.

A large projection screen dominating a gallery in Istanbul Modern Art Museum confronts you with a discomforting cage, a performance art piece by Nezaket Ekici (1970-), wearing an Alice-in-Wonderland-style dress.

In ‘But All that Glitters Is Not Gold,’ the challenge is to choose the right one from among the many identical-looking keys hanging at various distances around the cage. What initially looks like a fun game over time becomes an agony.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above: “But All that Glitters Is Not Gold,” Nezaket Ekicic, 2014

In ‘Human Cactus,’ Ekici positions her body like a sculpture. She makes small movements like a plant…. The artist mimics a live form utterly different from human.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

I found her don’t-touch-me dress as claustrophobic and confining as the cage.

Above: “Human Cactus,” Nezaket Ekicic, 2012

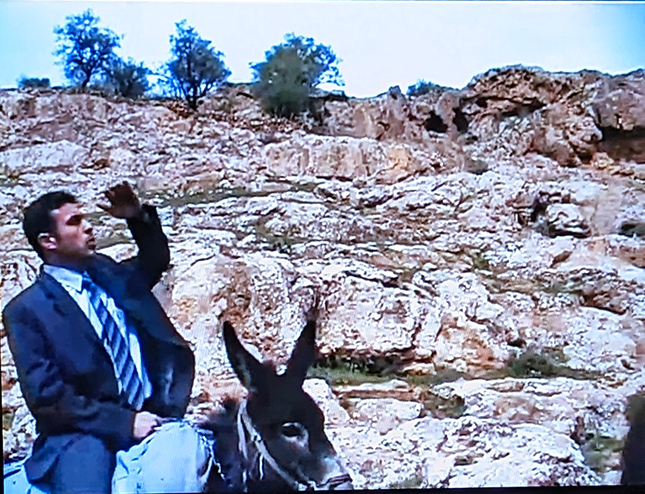

Halil Altindere (1971-) is known for approaching social and political issues with a touch of humor. In the photo below, he combines a donkey in a commonplace country scene with the incongruous presence of a man in coat and tie.

The artist’s video installation, “Metaverse:”

…features elements relating to space and earth where symbols from North American culture cover a planet…. The video suggests an alternative world shaped by technology and digitalization.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above left photo, and a partial screen capture of digital animation on right: “Metaverse,” 2022. Both by Halil Altindere.

Artist Inic Eviner (1956-) incorporated multimedia forms in her video installation, “National Fitness.” She employed videos and images from the May 19th commemoration of Ataturk (Mustafa Kemal, 1881-1938) Youth and Sports Day, a national holiday recognizing the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence in 1919.

I thought it was in architecture that I could most clearly see the impact of modernism on national identity…. One of the scenes… was the May 19 pageants from my own memory. These pageants, during which we wore uniforms with shorts or miniskirts that reflected the official ideology, ended with our being watched hungrily by crowds of men who made provocative comments. I was caught between severe shame and my duty as a patriotic girl. I wanted to transform these images of women…, invite them onto the stage and give them an active role. The women began to move on their own, independent of me, and like children disrupt the established patterns of meaning.”

Inci Eviner, website

Above left: “National Fitness,” Inci Eviner, 2013. Right: Ourselfie.

Born in Istanbul, Selma Gurbuz (1960-2021) studied art at Exeter College at Oxford before returning to complete her MFA at Istanbul’s Marmara University.

Gurbuz drew from both Eastern and Western cultures…. Black figured heavily from the start… as Gurbuz often used the hue to limn blurry scenes and indistinct, shadowy beings…. She frequently depicted fantastic occupants of a dreamlike world, representing kind of an intercultural, and in some cases interspecies, synthesis. Gurbuz was consistently drawn to the concept of connectivity, between past and present, human and nature, myth and reality.”

“Selma Gurbuz,” Artforum, April 27, 2021

Above top left: “Self-Portrait” and “Faded Costume,” 2004. Bottom left: “Evil Eye,” 2004. Right: “Hand Globe,” 2008. All by Selma Gurbuz.

Bedri Baykam (1957-) combined photography and painting in “Ingres, Gerome, This Is My Bath” to unveil:

…the West’s appropriation of the history of modern art and its cultural imperialism over the Third World…. The left side was adapted from Ingres’ ‘Turkish Bath,’ the right side from Gerome’s ‘Grand Bath at Bursa,’ and Baykam secretly included himself in the painting…. (It) may be interpreted as an insider’s answer… to the way foreign painters, who couldn’t enter a bath or harem, were captivated by them and imagined then in erotic terms, from an Orientalist point of view.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above: “Ingres, Gerome, This Is My Bath,” Bedri Baykam, 1987.

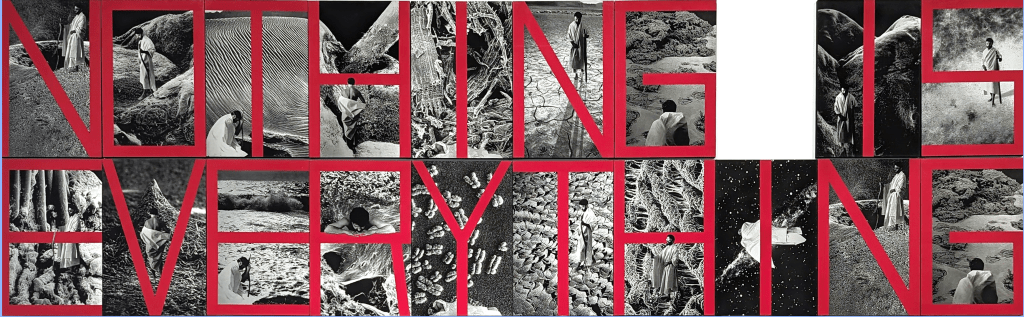

The work ‘Nothing is Everything and Everything is Nothing’ represents a quest for meaning…. In each of the letters in the work, Balkan Naci Islimyeli positions himself as a kind of wanderer who has taken to the road. With a staff in his hand, the artist travels through all sorts of lands and goes to outer space, visualizing this quest through his work.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above: “Nothing Is Everything and Everything is Nothing,” Balkan Naci Islimyeli (1947-2022), 1995.

Balkan Naci Islimyeli scrutinizes his own position between East and West, past and present, while likewise forcing viewers to reconsider their own positions within the cultural chaos of Turkey today, and the country’s place in the contemporary world.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

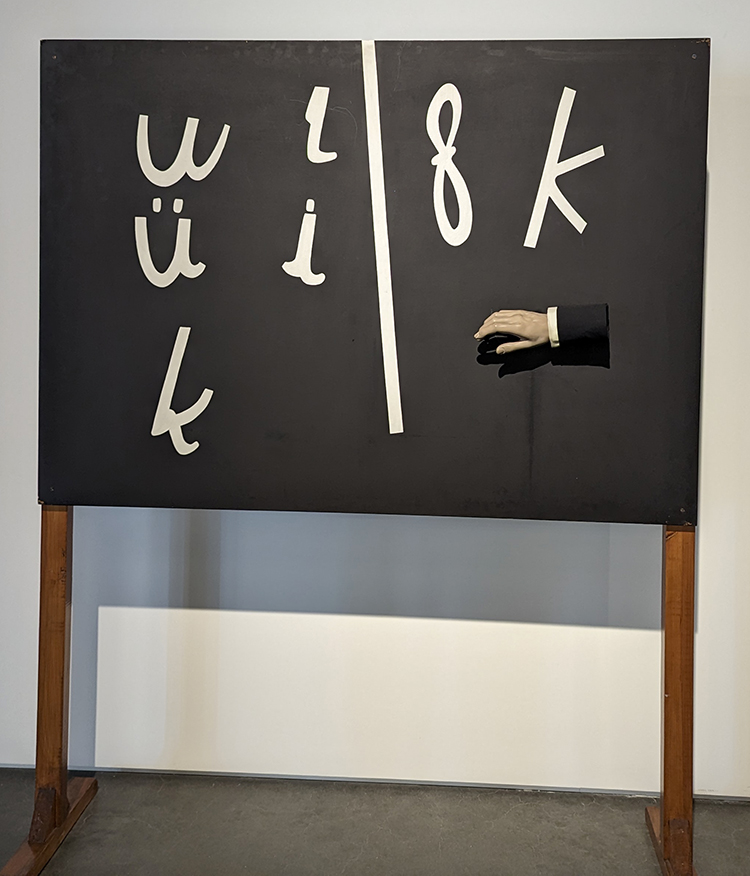

As a foreigner, the blackboard in the postage stamp at the top of this post and in the photo below had little meaning, but any schoolchild in Turkey would know its significance. Aydan Murtezaoglu (1961-) based it on a famous 1928 image of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938) unveiling a new, simplified Turkish alphabet to replace traditional Arabic script. Traditional Arabic script still is found on the innermost walls of mosques. The blackboard is symbolic of the separation of church and state, a line increasingly blurred in today’s landscape.

Top left: “Straitjacket,” Balkan Naci Muslim, 1990. Right: “Blackboard with Dressed Mannequin Hand,” Aydan Murtezaoglu, 1993. Bottom left: “Skinless,” Inci Eviner, 1996.

Semihi Berksoy painted self-portraits or included herself, her family, and her friends from the art world in her paintings. She interwove the characters she portrayed on stage… with her life with art; she interwove reality with dream in a poetic and tale-like style…. Berksoy’s works offer information, references, and codes for understanding not just her art but also the history of culture and arts in Turkey.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Semiha Berksoy (1910-2004) was Turkey’s first opera star to perform at the Berlin Academy of Music, as well as a prominent visual artist. While the painting below appears as perhaps a poster advertising Tosca, “Feast at the Prison” features three writers who spent multiple years imprisoned in Turkey for their political activism.

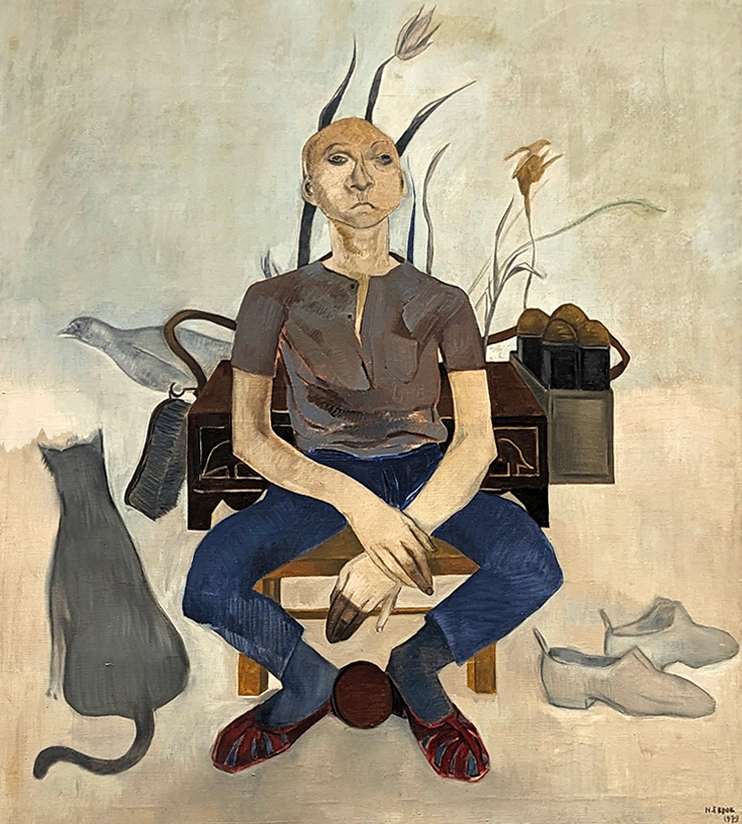

Above left: “Shoe Shiner,” Nes’e Erdok (1940-), 1979. Right: “Feast at the Prison,” Semiha Berksoy, 1999.

Known for his socio-critical paintings, Mehmet Guleryuz’ (1938-2024) figures are in motion even when they are standing still. He believes that the easist way to discover human beings is to explore the extreme poles of the human condition.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

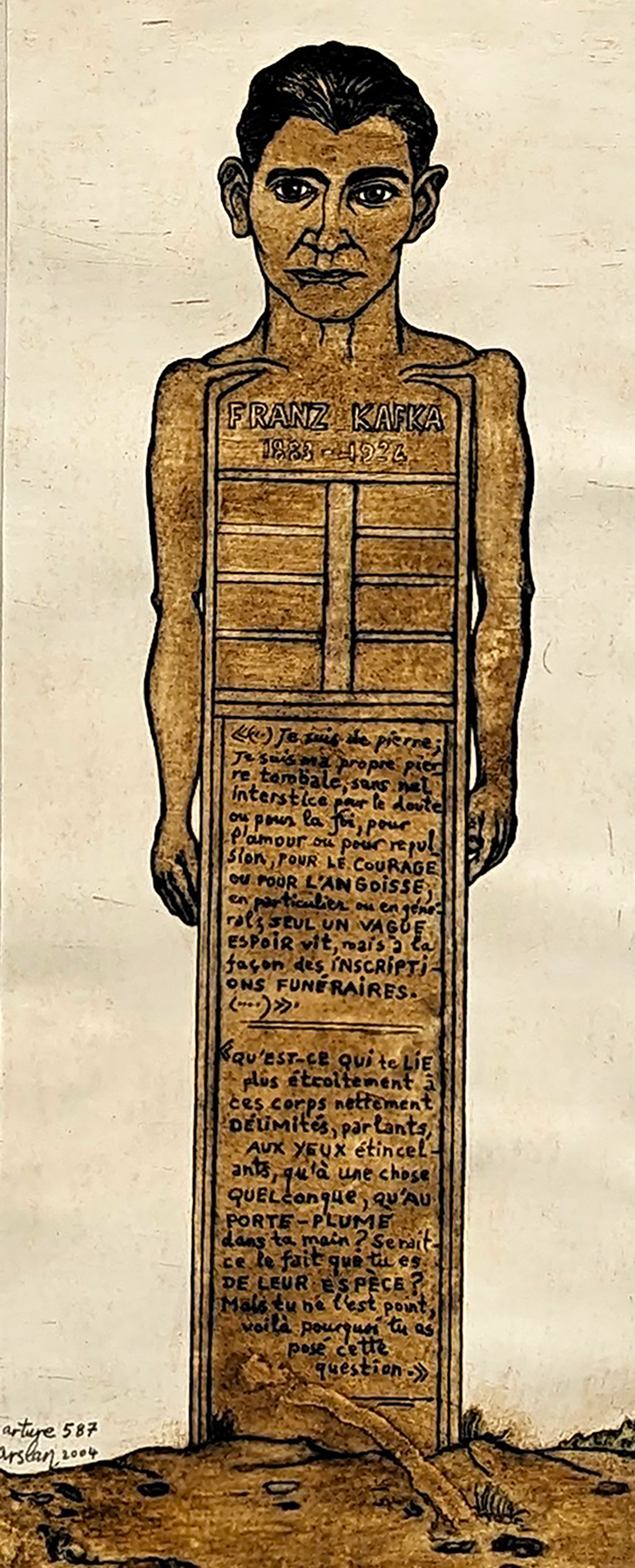

Above left: “Motard III,” Mehmet Guleryuz (1938-), 1996. Middle: “Arture 587,” Yuksel Arslan, 2004. Right: Detail of Guleryuz’s “Motor Car.”

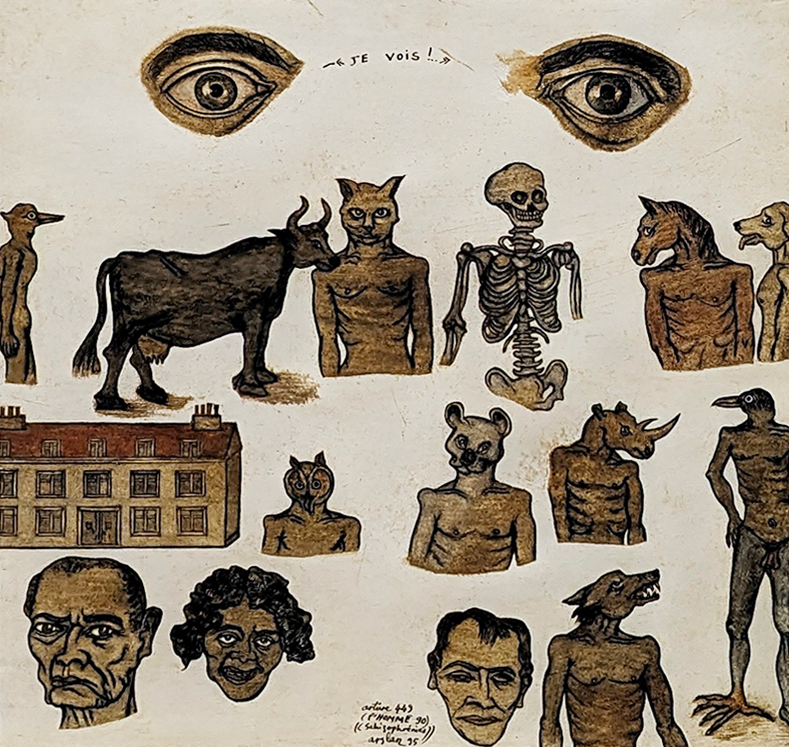

Yuksel Arslan (1933-2017) disliked having his artworks labeled “paintings.” His invented portmanteau to describe them was “arture,” a combination of the word “art” and the ending of the French word for painting, “peinture.” Numerous artures feature the traditional shape of Muslim gravestones, reflecting his childhood explorations of the ancient cemetery in Eyup, Istanbul.

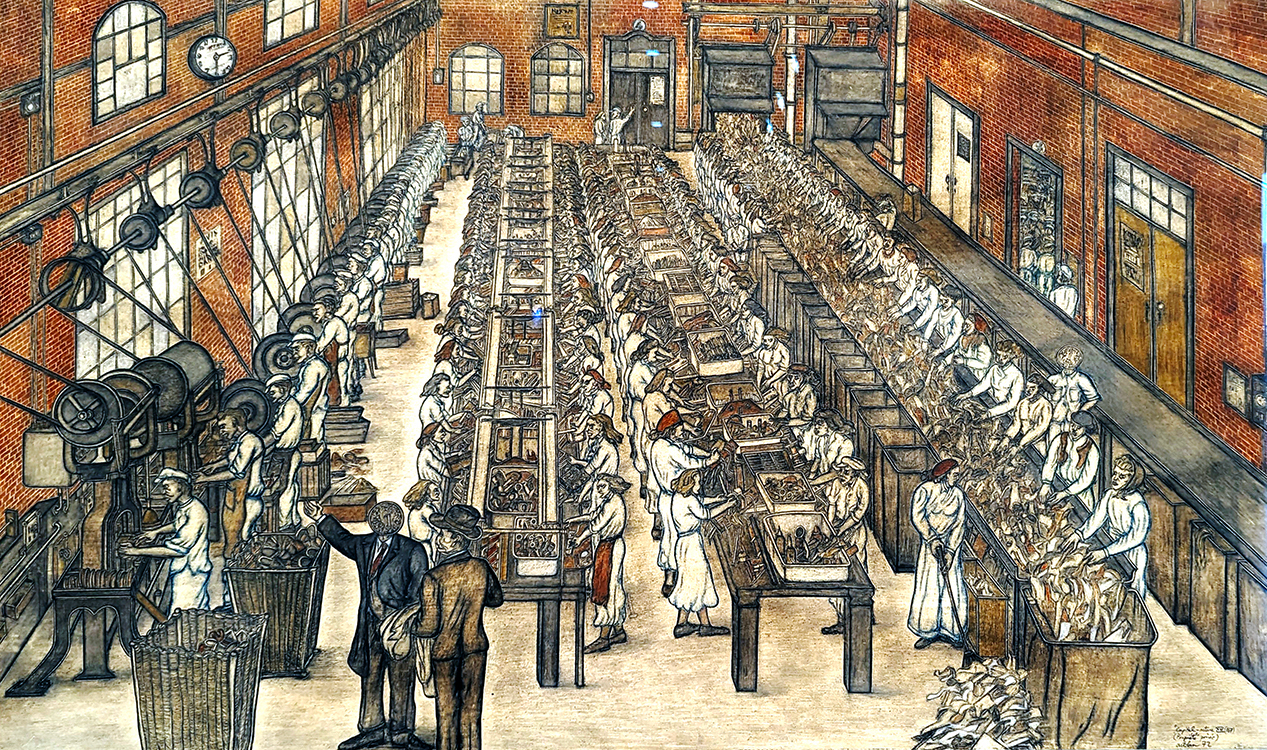

In ‘Arture 167, The Capital XVI, (Private Property),’ Yuksel Arslan visualizes the effects of capitalist production processes on society and individuals through symbolic language. Based on Karl Marx’s ‘Das Kapital,’ the artist depicts hundreds of workers in a mass-production factory as standardized beings like the products they produce and industrialists as mere representations of their ideologies with coins in place of their faces.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above left: “Arture 449, Je Vois,” 1995. Right: “Arture 167, The Capital XVI, (Private Property),” 1972. Both by Yuksel Arslan.

Cihat Burak’s subject is a memorial to the ‘romantic revolutionary’ poet Nazim Hikmet…. in prison, wrapped in a green coat, his head swollen with lines of poetry. Flowers and birds, normally lighthearted motifs, are here weighted down by unrequited love…. The center panel, showing his dead body, suggests he was killed in a street riot… although he actually died of a heart attack in 1963. The cobblestones are uprooted as though waiting for a revolution, and the pastiche of imagery from the past and the present gives the work a surrealist sensibility. At the top of the third panel Hikmet is portrayed as a young man wearing an Ottoman fez…. but perhaps the most striking figures are those that Burak perceives as carrying on the legacy of protest long after Hikmet’s death.”

Curator’s Notes, Istanbul Modern

Above left: “Kadikoy I,” Oddviz Artist Collective, 2018. Right: “Death of a Poet,” Cihat Burak (1915-1994), 1967.

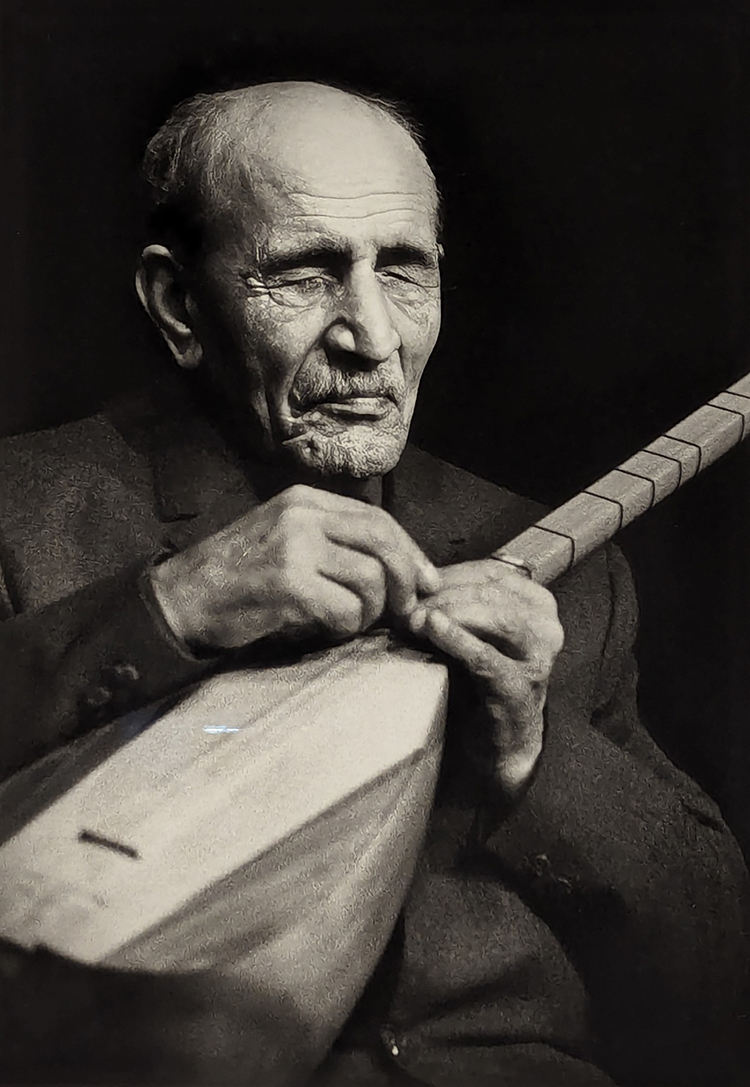

We were fortunate to catch a retrospective exhibition of 70 years of work captured by the lens of Ozan Sagdic (1934-). The photojournalist has documented the country’s history with images of both the country’s leaders and people in everyday situations.

I like to shoot people, interpersonal relationships. I love photos that convey irony. For example, there must be either a contradiction or a harmony. The photo has two dimensions. One is external aesthetics, texture, composition, perspective – these are things that can be taught and learned. But the other dimension is ‘interior aesthetics.’ It’s not something that can be learned – to give soul to photography, to breathe soul.”

Ozan Sagdic interviewed by Riza Ozel for TFMD Photojournalist Magazine

Above: Photographs by Ozan Sagdic from a retrospective exhibition, “The Photographer’s Testimony.”

The world is in constant motion, evolving with time, and so too must the spaces we inhabit. Architecture is a mirror to these changes, a built expression of our shifting needs, aspirations, and values. It should not be static or closed; it should invite, engage, and inspire. Buildings should open themselves to the world. They should awaken curiosity, spark connections, a cultural attitude that brings people together.”

Website of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop

Designed by the architectural firm founded by Pritzker Prize Laureate, Renzo Piano (1937-), the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art opened in 2023 on the waterfront where the Bosphorus and the Golden Horn meet. The spacious museum provides multiple floors of galleries designed to accommodate large exhibitions of contemporary art. With a shimmering reflecting pool, the rooftop offers stunning views of the water and the city in all directions.

Museums requiring security checks are commonplace everywhere, but the first security check for the entire area was outside the vast plaza fronting the building. Instead of integrating it into the culture of the city as Piano envisioned; it isolates it from the bustling streets outside.

The whole complex becomes lumped together with the adjacent Galataport Istanbul luxury mall, patronized by the elite who arrive from the suburbs via automobile and passengers disgorged from cruise ships. Opened in 2021, the mall forms a barrier insulating tourists from experiencing the real Istanbul.

Above top left: The 1826 Nusretiye Mosque next to Istanbul Modern’s sculpture, “Runner,” Anthony Cragg, 2017. Right: View from museum terrace. Bottom: Mezzanine level inside Istanbul Modern.

I found myself drawn to contemporary art exhibits whenever and wherever we encountered it in Istanbul, longing for them to serve as signs of a country where modernity is embraced freely. But the cultural leap from the traditional Nusretiye Mosque outside to the museum is enormous.

And the contemporary art housed within Istanbul Modern seems counter to the president’s espoused role for women – in the home with three or more children.

You cannot bring women and men into an equal position; this is against nature.”

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Certainly, the museum would not be there if not sanctioned by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He is also the same man who smudges the lines between separation of church and state, controversially opening an enormous new mosque in 2021 on Taksim Square, the square long considered a symbol of the secular republic.

The extreme contrasts in Istanbul kept me off-balance. Walking into a mosque head-scarfed and being shuffled off into a screened-off holding pen – out of sight, out of mind of the privileged males worshiping under immense domes – bothered me. Even though I grew up during a time when Catholic women always had to wear a hat or mantilla to church, I felt unjustly cloistered. Caged.

Istanbul reminds me of one of those topsy-turvy double-ended dolls that you turn over, flip the skirt the other direction and have a completely different character. Walking through neighborhoods, there can be a radical shift from street to street – as though the women draped in dupattas, chadors and niqabs were cartwheeled into western wear of tight pants or miniskirts paired with midriff tops.

Even religious buildings seem double-ended. The landmark Hagia Sofia was erected as the seat of the Greek Orthodox Church by Byzantine rulers 1,500 years ago. Its usage flipped when the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople, now called Istanbul, in 1453. The intricate Christian mosaics were covered and garbed with Islamic calligraphy. Under Ataturk, Hagia Sofia was secularized and transformed into a museum spotlighting both its Christian and Islamic art. Flipped again in 2020 by President Erdogan, Hagia Sofia is now a mosque, with remnants of early Christian mosaics only visible in the galleries above the main floor.

And then there’s the art, with scarcely a trace in the city illustrating any transition from the ancient or traditional to modern and contemporary.

As I wrote above, such strong divisions throw me off balance. Returning home did not erase that feeling. This country also is split, as split as if the Statue of Liberty herself has been turned topsy-turvy, her new garb unbecoming and snuffing out the torch she bears.