Above: Detail of 4,213 cigarette butts collected and dated for exhibition in the Museum of Innocence

When those visiting my museum note that beneath where each of the 4,213 cigarette butts is carefully pinned, I have indicated the date of its retrieval. I hope they will not grow impatient, thinking I am crowding the display cases with distracting trivia: Each cigarette butt in its own unique way records Fusun’s deepest emotions at the moment she stubbed it out.”

Kemal, the main character and the narrator of Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk

Nothing I could possibly dream up could convey obsession with such immediate clarity.

The top quotation from Kemal’s thoughts in Orhan Pamuk’s 2009 novel, Museum of Innocence, does not appear until Chapter 68 of the 83-chapter book. The entire chapter is devoted to these fetish souvenirs of unobtainable love.

However, this represents no plot-spoiler as the wall of lipstick-stained cigarettes is the first thing encountered in the related museum of the same name in Istanbul. The actual Museum of Innocence was conceived of by its author simultaneously with the book, and the museum’s website proclaims they can be experienced in any order or independently.

Pamuk’s love of Istanbul made the city a main character in his book, compelling me to plunge into it as we headed that direction. I couldn’t finish it. Kemal’s years-long destructive obsession with Fusun, a young woman distantly related, overwhelmed me even more than her. Enervated by it, I stopped close to the halfway point and declared I thought a visit to the museum would be of no interest to me or particularly to anyone who had not read the book.

I was conflicted. The Museum of Innocence was but three blocks away from the neighborhood apartment where we were staying for a month, and it receives high praise as one of the city’s top museums. Collectors and their compulsive hoarding fascinate me, and the intriguing intimacy of house museums tends to please me.

So, there we were, confronting the butts surreptitiously pocketed by Kemal, the shape and appearance of each crushed stub a barometer of Fusun’s mood on the day it was smoked.

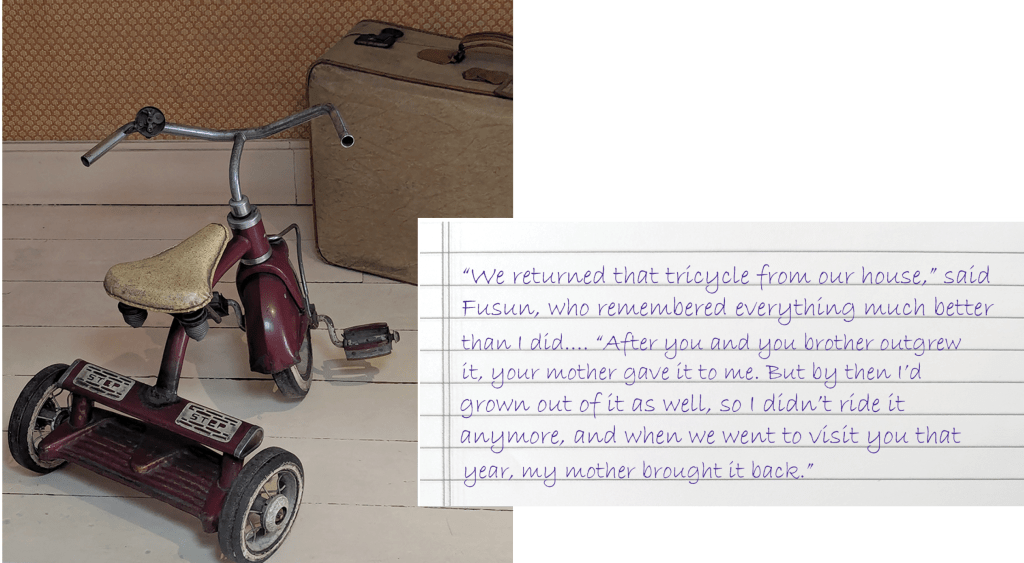

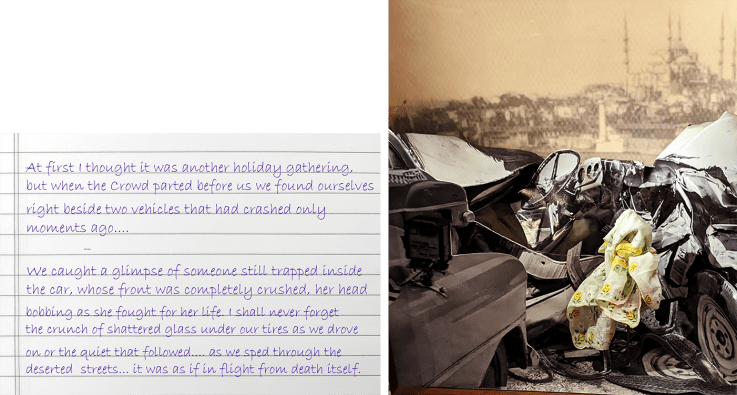

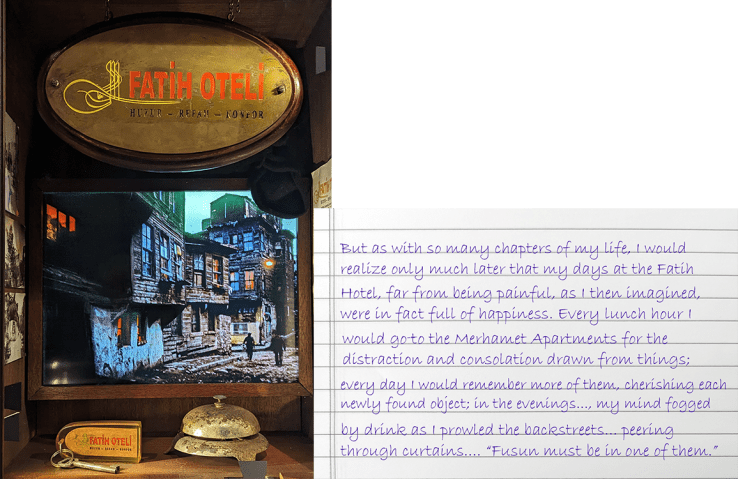

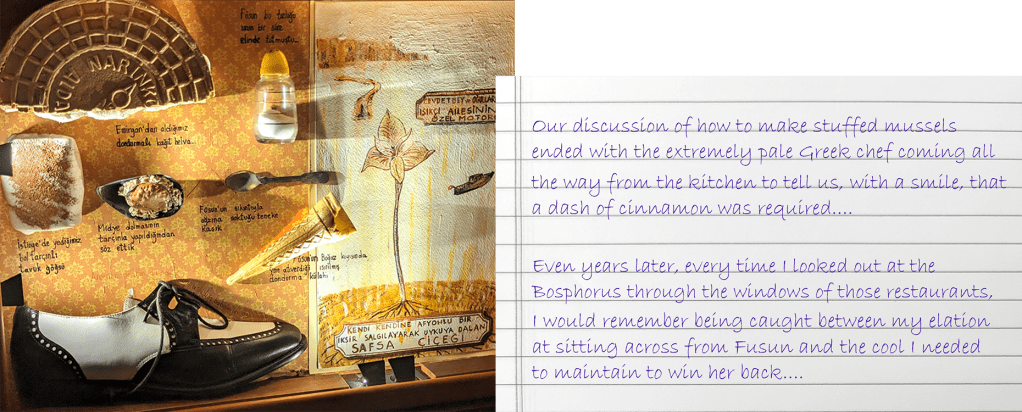

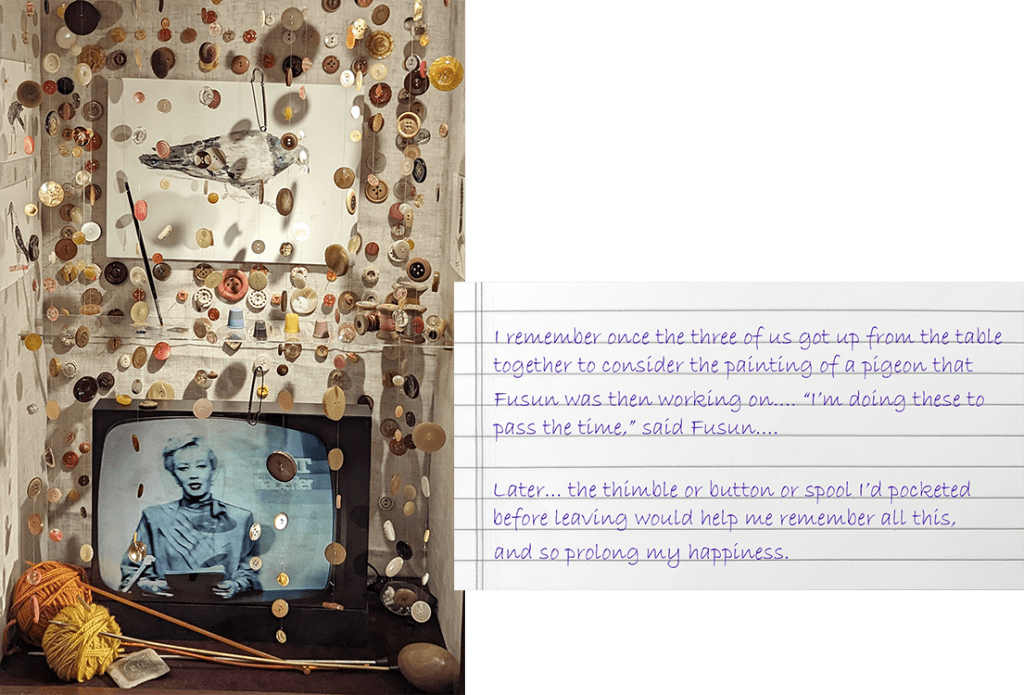

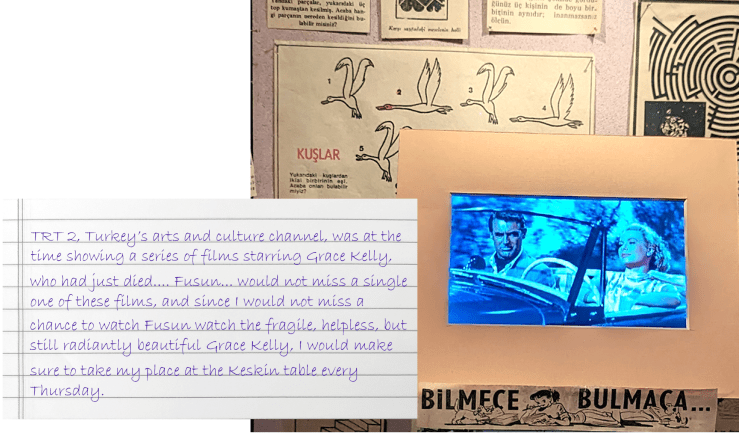

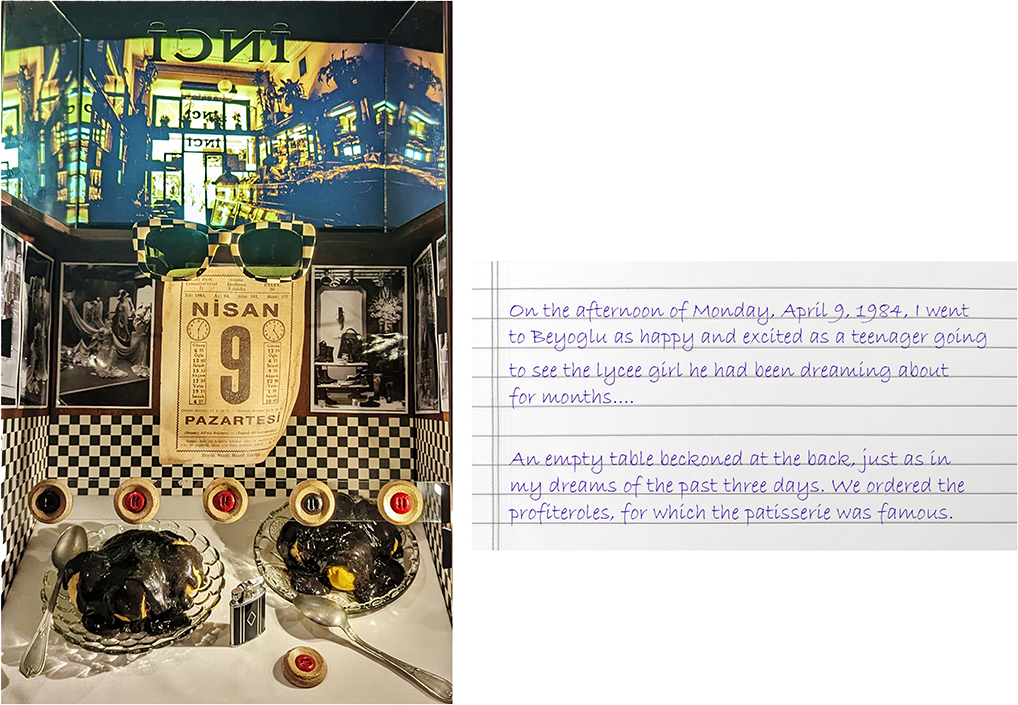

Aside from the cigarettes, Kemal in the book, and obviously Pamuk in real life, collected a houseful of everyday objects, many pilfered during Kemal’s suppers with Fusun’s family (fiction) or purchased by the author combing neighborhood antique shops and Istanbul’s flea markets. Having a Nobel Prize in Literature and several bestsellers already under his belt no doubt helped the writer complete his monumental assemblage.

Each chapter of the book unfolds in the museum with its own vignette. Drawn from Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, the quotations I’ve paired with the photos are in chapter-order as well.

Above: Keys? Salt shakers? Compulsive collecting of everyday objects evoking memories.

Above: The bathroom mirror allows visitors to step into Kemal’s reflections. This particular display bothered me though because the grunge and decay indicated a greater degree of poverty in Fusun’s parents’ home than I sensed in my reading.

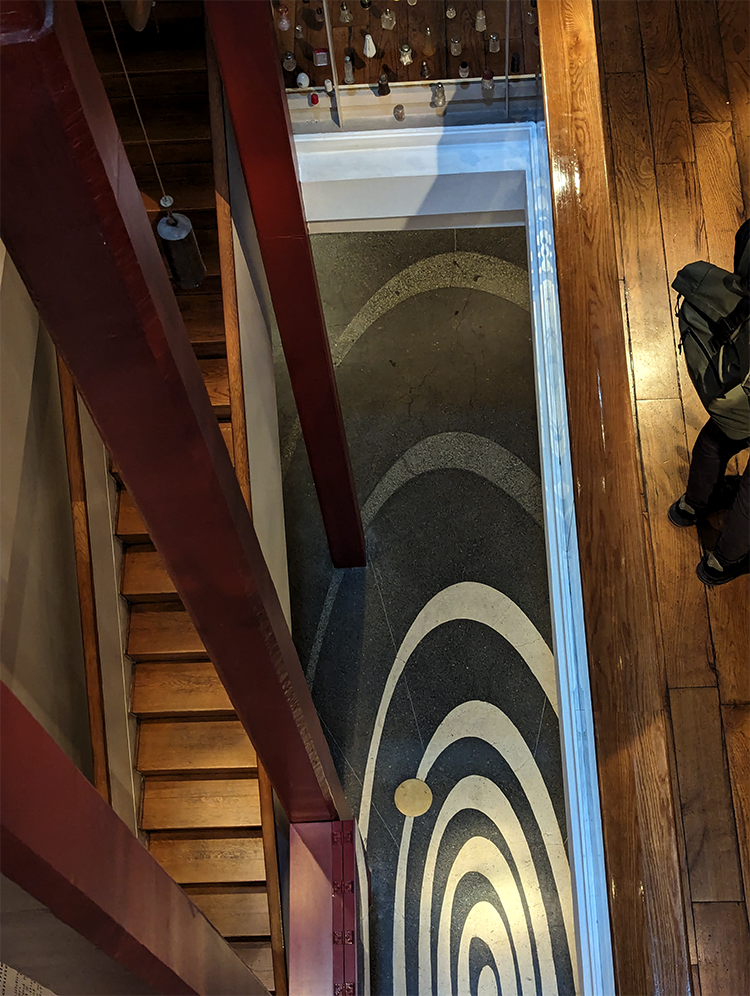

Above: The narrow apartment of the Museum of Innocence attracts all ages, many taking time to listen to the long, narrated guide via headsets.

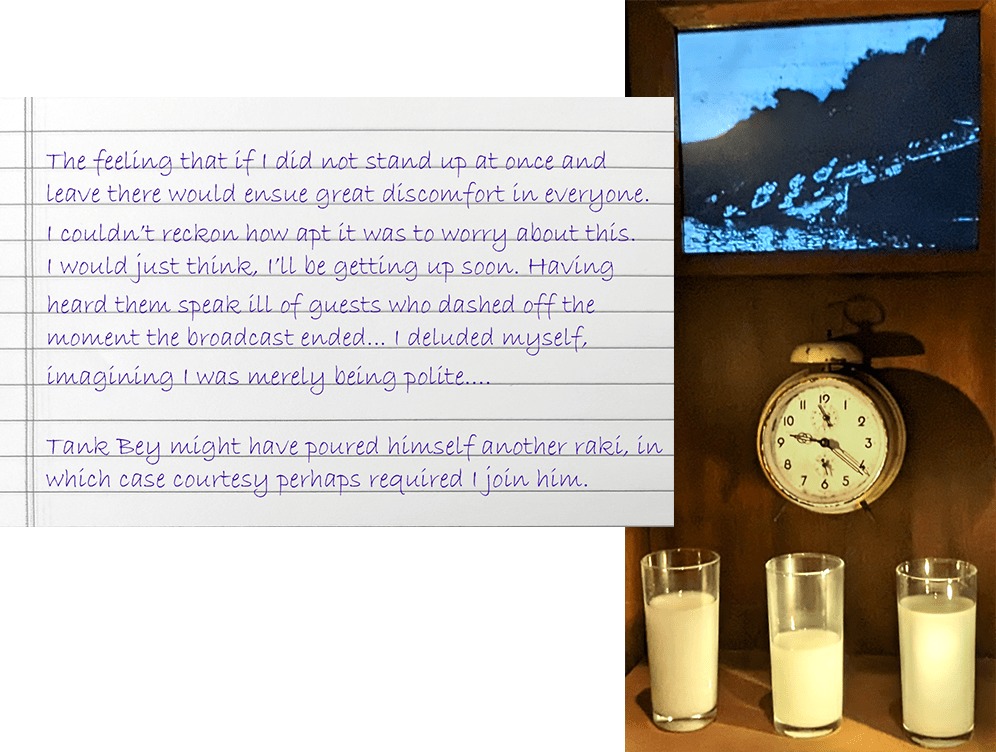

Above: In addition to cigarettes smoked, much anise-flavored, 80+-proof raki was downed in the novel, as one would expect in Istanbul.

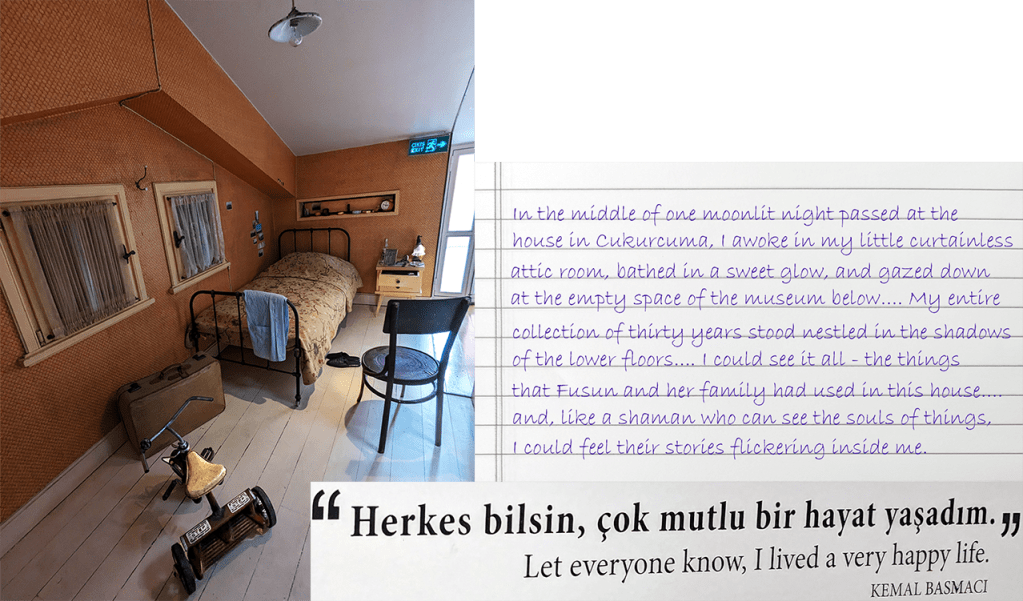

Above: My favorite sentence of the entire book.

Happy? While Kemal expressed great pleasure in even the most mundane items Fusun had touched, his story never began to approach my definition for happiness. It resembled more a lifelong period of mourning for someone not within grasp.

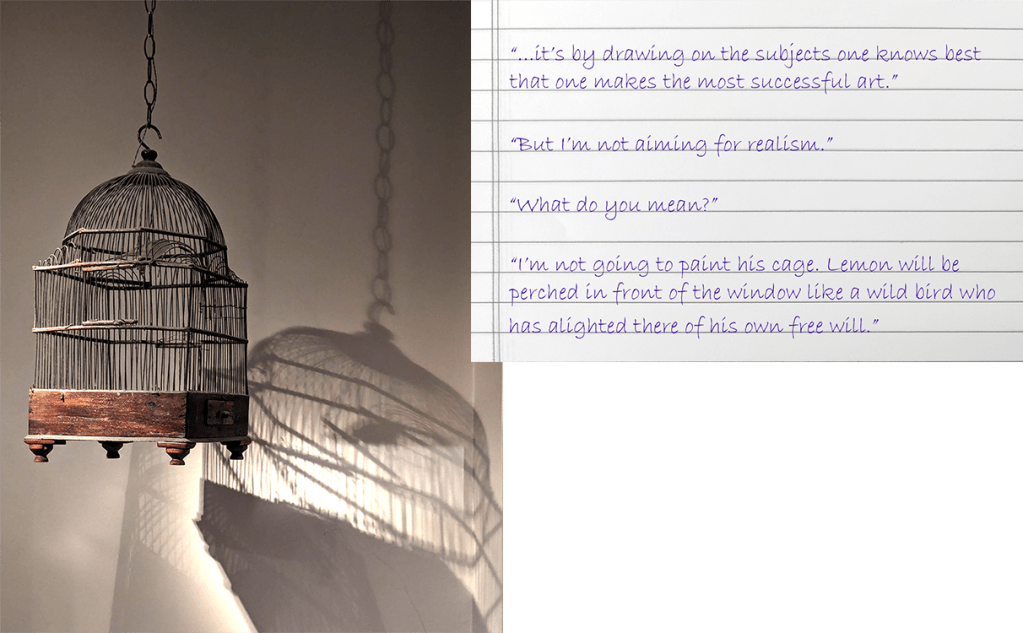

Like her parakeet Lemon, Fusun was imprisoned in a cage formed by a restrictive society and Kemal’s claustrophobic attention. Star-crossed, their dreams were never the same.

Surprisingly, my husband, who had read not a page of the book, enjoyed the museum as much as I did. The visit sent me diving back in to finish the novel, and the pairing of the two experiences altered my initial impression of the book. I now find the book and museum both complementary and inseparable.

The complexity of distinguishing Kemal from the author adds to the mystique of Pamuk’s unusual undertaking. Pamuk was writing Kemal’s “thoughts” while actually assembling the collection for the museum in real life, blurring the line between fact and fiction.

And, yes, I do recommend experiencing them both. Why else would I write such an obsessive post?

Museums should explore and uncover the universe and humanity of the new and modern man emerging from increasingly wealthy non-Western nations…. The stories of individuals are much better suited to displaying the depths of our humanity. It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale….

Monumental buildings that dominate neighborhoods and entire cities do not bring out our humanity; on the contrary, they quash it. Instead, we need modest museums that honor the neighborhoods and streets and the homes and shops nearby, and turn them into elements of their exhibitions. The future of museums is inside our own homes.”

Excerpt from “A Modest Manifesto for Museums” in the Museum of Innocence