Above left: Monumental effigy of Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1587). Above right: Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). Lady Chapel, Westminster Abbey

There is no other shelter hereabouts: misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.”

The Tempest, William Shakespeare, 1611

In recent years, you’ve been exposed to an immense quantity of footage showing the interior of Westminster Abbey: the wedding of Prince and Princess of Wales in 2011; the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022); and the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla in 2023.

With no need to cover that aspect, this taphophile is jumping straight to the everyday role of Westminster – a splendid monumental cemetery housing the remains of more than 3,300 elite, a veritable who’s-who of a thousand years of British history. Grave markers underfoot lie ignored, overwhelmed by the sculptural and polychrome effigies and memorials climbing ever higher up the church walls.

If ghosts rise in the night, what bedlam must reign. According to the Westminster website, the remains of 13 kings, four queens regnant, 11 queens consort, and two more queens are interred there. Blood might run thicker than water, yet British bluebloods frequently spilled that of their kin.

In days of yore, Catholics had to be buried in consecrated ground, meaning inside or adjacent to a church, in order to ascend to heaven. Resting under that soaring Gothic vault surely should bring one closer. Of course, once dead, one has little choice of neighbors or even whether your spot remains properly consecrated.

The gossip-churning spats amongst King Charles III’s extended family are small potatoes by comparison. Capture the flag was no game; there were bloodbaths. Feuds were further fueled by the clumsy, seesawing swings from Catholicism to Church of England, which I’ll simplify greatly by blaming lust-driven King Henry VIII (1491-1547).

Heat not a furnace for your foe so hot that it do singe yourself.”

Henry VIII, William Shakespeare, 1613

Despite the breathtaking beauty of its elegant, lacy, fan-vaulted ceiling, the Lady Chapel tombs serve as memorials to the tangled mess Henry VIII bequeathed his country. It’s no secret Henry sowed his seed and disposed of wives by any means possible, a questionable habit that led him to break away from the confines of the Catholic Church because the Pope refused to sanction his annulment maneuvers. Henry tastefully waited a day after having his second wife beheaded to marry his third, Jane Seymour (1508-1537), who managed to produce a male heir to the throne and was the only wife to die of natural cause before the king tired of her.

Following Henry’s death, Jane’s nine-year-old son was crowned Edward VI (1537-1553) in Westminster Abbey. During his reign, the Church of England discarded the Latin prayer book in favor of one in English. As he lay dying of tuberculosis, the teenaged king fretted about the existing line of succession.

Edward’s oldest half-sister, Mary (1516-1558), was the only surviving offspring of Henry’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). The boy king feared Catholic-raised Mary would reject the conversion to the Church of England. Conveniently, as Mary was the child of an annulled marriage, albeit one that lasted 27 years, one could argue she was illegitimate.

Heaven witness I have been to you a true and humble wife, at all times to your will conformable, ever in fear to kindle your dislike, yea, subject to your countenance, glad or sorry as I saw it inclined. When was the hour I ever contradicted your desire, or made it not mine too?”

Catherine of Aragon in Henry VIII, William Shakespeare, 1612

Edward also applied the same justification to eliminate his half-sister Elizabeth, the child of second wife Ann Boleyn (1507-1536), whose marriage to Henry VIII was annulled, not by the pope, the day before he ordered her beheading.

So, upon Edward’s death, his young Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey (1536-1554), was pronounced his successor. Nine days later, even before an official Westminster coronation, support for Lady Jane amongst lords and house members of the Privy Council waivered. Mary quickly began taking actions to surpass even Edward’s “wicked-stepsister” fears. After rounding up forces to depose Jane, Mary had Jane imprisoned in the Tower of London and later beheaded for treason.

Mary wed Prince Philip (1527-1598) of Spain, who was crowned King Philip II of Spain in 1556, three years into their marriage. This union temporarily forged a potent Catholic alliance.

Of course, the recently empowered Protestants were disgruntled by the queen’s appointments of Catholics to plum positions as well as her marriage. An attempted rebellion, including plans to install the Protestant-leaning Elizabeth as queen, was quashed. Although Elizabeth denied involvement, Mary had her locked up in the fortress Bell Tower and later confined to a gatehouse at Woodstock Manner.

By late 1554, Queen Mary I reached an agreement with the pope to return the Church of England to Roman jurisdiction. The Heresy Acts repealed by her father were put back in place. And enforced.

Many wealthy Protestants fled the country; numerous ones refusing to convert to Catholicism were imprisoned. The executions of those defying her began in earnest in 1555 – close to 300 men, including Protestant bishops and the Archbishop of Canterbury, were burned at the stake. Protestants deemed the Catholic queen Bloody Mary.

Childless and ill, Mary knew she had to name a successor. Protestants who detested Queen Mary I campaigned for Elizabeth. If Queen Mary skipped over her half-sister, the next relative in line was Mary Queen of Scots, a candidate eliminated as her husband at the time was heir to the French throne. With Spain and France enemies, King Philip would never tolerate that merger of crowns.

The queen was compelled to accept her stepsister Elizabeth. Before any schemes for her overthrow in favor of Elizabeth met with success, Queen Mary died from cancerous cysts misdiagnosed as a false pregnancy.

So the country was flipped back to Church of England. Queen Elizabeth I felt no need to persecute Catholics. As long as they were loyal to her. Turning a blind eye to religious beliefs or practices in the home proved effective for maintaining relative calm for the first decade or so of Queen Elizabeth’s reign.

The Papal Bull of 1570 brought long-simmering issues to a boil. Pope Pius V (1528-1572) labeled Elizabeth illegitimate and excommunicated her for heresy. His interfering proclamation also absolved her Catholic subjects from allegiance to her. The pope uged Mary Queen of Scots to restore Catholicism in her realm.

Mary Queen of Scots, however, was in no position to rally forces in England, much less in Scotland. After her 16-year-old husband, King Francis II (1544-1560) of France died of an ear infection, Mary returned to a Scottish kingdom now Protestant.

Mary’s choice for her second husband posed a threat to her cousin, Queen Elizabeth. Henry Stewart, the Lord Darnley, was Mary’s second cousin. Without tracing the entire family tree, any offspring of the pairing would have claims to both the Scottish and English thrones.

The marriage quickly went down the tubes. Lord Darnley proved erratic in his behavior, exacerbated by his overconsumption of alcohol, and managed to offend many, including the queen. An understatement. Lord Darnlety had stormed into the queen’s chambers during dinner, accused her of adultery with her male secretary and ordered the Protestant nobles in his entourage to kill him. David Rizzio (1533-1566) was stabbed more than 50 times in front of the pregnant queen, restrained at gunpoint by her own dear husband.

A son was born a year into the marriage, Charles James (1566-1625). Before the future King James VI turned one, Lord Darnley went out with a big bang. While his wife was away, his quarters exploded, sending his body flying into the garden. He died not from the explosion but had first been strangled.

Suspicion fell upon James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell (1567-1578), a close confidant of the queen. The earl was acquitted of the murder, and he and Queen Mary were married a mere three months after her husband’s death.

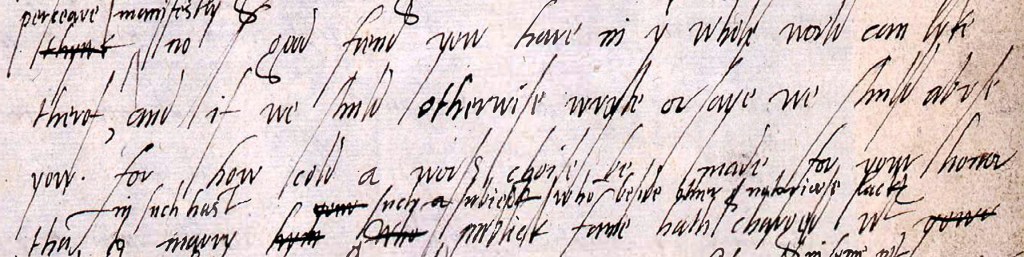

Madame, to be plain with you, our grief has not been small that in this your marriage so slender consideration has been had that, as we perceive manifestly, no good friend you have in the whole world can like thereof…. For how could a worse choice be made for your honour that in such haste to marry such a subject, who besides other and notorious lacks, public fame has charged with the murder of your late husband?”

Excerpt of a letter from Queen Elizabeth I to her cousin, Mary Queen of Scots, edited by William Cecil, June 1567, obtained from “Murder at Kirk o’ Field,” National Archives, United Kingdom

This advice from Queen Elizabeth I was based on experience. Her own rumored paramour, Robert Dudley (1532-1588), fell under a cloud of suspicion when his wife was found dead at the bottom of a long flight of narrow stairs. If the pair had ever hoped to marry, this unfortunate event led Queen Elizabeth to never pursue it.

Unfortunately for Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth’s disapproval of such a union was correct. The hasty marriage appeared to implicate Queen Mary herself, providing prominent Protestant noblemen with an excuse to revolt. Mary was forced to abdicate her throne and flee to England, seeking the protection of her dear cousin, Queen Elizabeth.

That protection took the form of imprisonment. For 19 years. Throughout those years, advisors to Queen Elizabeth counseled that, as long as her cousin remained alive, Catholics would conspire to install her as Queen of England. Queen Elizabeth ordered the execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1587.

Queen Elizabeth’s reign endured and her kingdom flourished until her death years later. We’re skipping over those years to bury her, which is what this post set out to explain. Let’s do a who’s-buried-where catch-up.

Henry VIII’s dreams of a grandiose tomb for him and his queen in Westminster Abbey began to take shape about three decades prior to his death. Through the years his plans grew grander, while which queen would occupy it with him fluctuated. He left detailed instructions for this memorial to be much larger than the one for his father and mother nearby. As his end approached, he requested to be temporarily interred with his third wife Jane, the mother of King Edward VI, in St. George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle.

Spend no time seeking his memorial at Westminster though because no following monarch ever allocated enough funds to construct it. The only wife of King Henry VIII’s to lie in Westminster is his fourth wife, Anne of Cleves (1515-1557), whose marriage to him was but seven months.

After hemming and hawing about whether funeral services should be in Latin or English, Queen Mary I finally had King Edward VI buried under the altar in the Lady Chapel of Westminster. Again, a planned monument never was funded, and there is only a black marble diamond-shaped marker in the floor of the chapel.

Queen Mary I’s eternal home was in a floor vault in Lady Chapel. Although her reign was lengthy, Queen Elizabeth I never found a minute to have a monument erected for her half-sister Queen Mary I.

And thus the whirligig of time brings in his revenges.”

Twelfth Night, William Shakespeare, 1601

The placement of Queen Elizabeth’s coffin directly atop of Mary I of England’s in that tomb seems an unwanted reunion for the feuding siblings. Mary Queen of Scots’ son, who assumed the monarchy as King James I after the death of the “Virgin Queen” Elizabeth, planned the duplex arrangement.

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs…. For heaven’s sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings, how some have been deposed, some slain in war, some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed….”

King Richard II, William Shakespeare, 1595

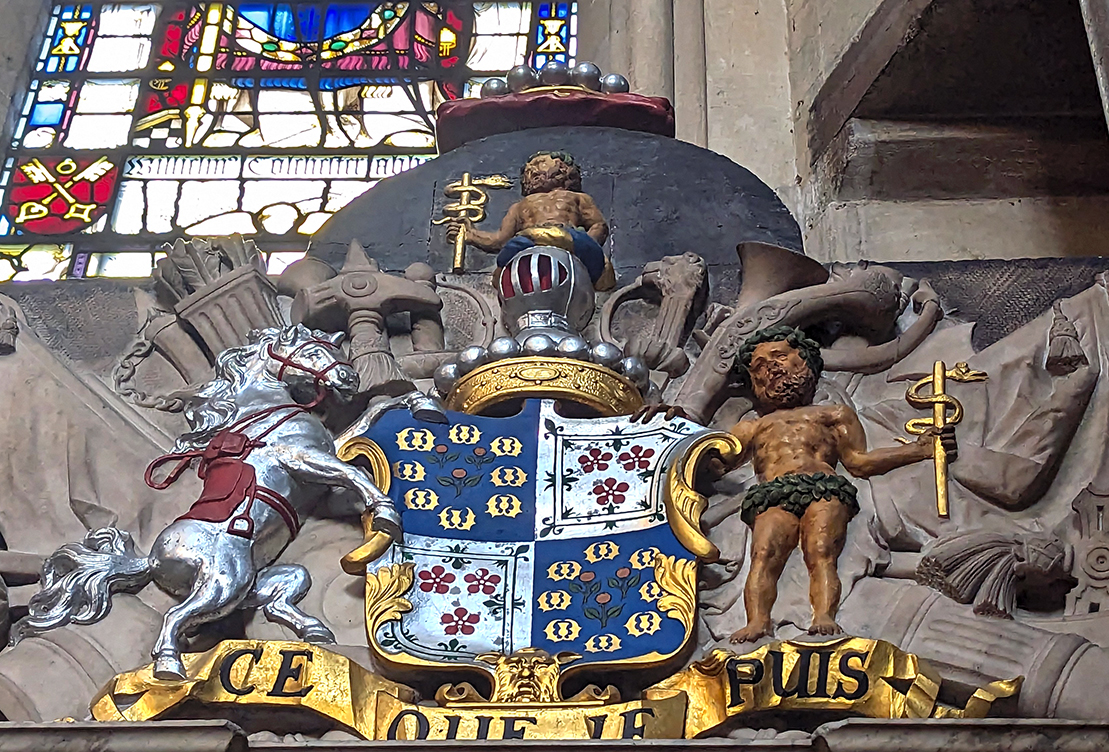

James did have the courtesy to commission an impressive columned compound above it housing a white marble recumbent effigy of Queen Elizabeth. Queen Mary I remained effigy-less. The inscription James I authorized for the monument bites with irony.

Partners both in throne and grave, here rest we two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, in the hope of the Resurrection.”

British history might have been less stormy had the “we” ever been “partners.” King James I planted yet one more tomb guaranteed to stir up trouble amongst the ghosts of Lady Chapel.

James was but a toddler when anointed King James VI of Scotland. He never saw his exiled and later executed mother again, his upbringing conducted by a series of often-cruel regents. Always believing his mother should have worn the crown of England, he transferred her remains to her rightful place in Westminster.

So, the step-siblings of Lady Chapel gained a new roommate. The conjoined-appearing photo crowning this post is not how the enemy cousins are entombed.

King James commissioned a magnificent, vaulted monument, ensuring it soared higher than that of Queen Elizabeth. This was inscribed with a lengthy epitaph:

To her good memory, and in eternal hope, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots….

Wife of Francis II, King of France: sure and certain heiress to the crown of England while she lived: mother of James, most puissant sovereign of Great Britain. She was sprung from royal and most ancient stock, linked on both paternal and maternal side with the greatest princes of Europe…. After she had been detained in custody for more or less twenty years, and had courageously and vigorously, (but vainly), fought against the obloquies of her foes, the mistrust of the faint-hearted, and the crafty devices of her mortal enemies, she was at last struck down by the axe (an unheard-of precedent, outrageous to royalty)….

Now she triumphs by death, that her stock might thereafter burgeon with fresh fruits…. May this precedent of the violent murder of the anointed Queen come to naught; may the instigator and perpetrator rush headlong to destruction.“

An excerpt from the translation of the Latin inscription on the tomb of Mary Queen of Scots

“For goodness sake” (Yes, it’s from Henry VIII.). Time to escape from this deep rabbit warren of royal treachery and intrigue I have plunged.

Although the bard William Shakespeare is buried in another haunt, he is memorialized in and dominates what is called Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. While Queen Elizabeth I was known to laugh heartily during plays of the bard, I confess to have delved into few since suffering to comprehend them in eighth grade. Too much, too early, “methinks” (Hamlet). Yet the sheer number of his words and phrases still in common usage never ceases to amaze me.

Above left: Memorial for William Shakespeare (1564-1616). Above right: Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

A bust of Samuel Johnson is an appropriate and immediate neighbor of Shakespeare’s. There were 42,773 words defined in Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, the first to employ literary quotations to illustrate those meanings. Shakespeare was among those he relied most heavily. Fifteen percent of the 114,000 quotations he chose to reference were lifted from the work of Shakespeare.

In the Oxford English Dictionary of today, Shakespeare receives credit for coining 1,700 words.

And, when I am forgotten, as I shall be, and sleep in dull cold marble, where no mention of me more must be heard of.”

Henry VIII, William Shakespeare, 1613

The rest is silence.”

Hamlet, William Shakespeare, 1600