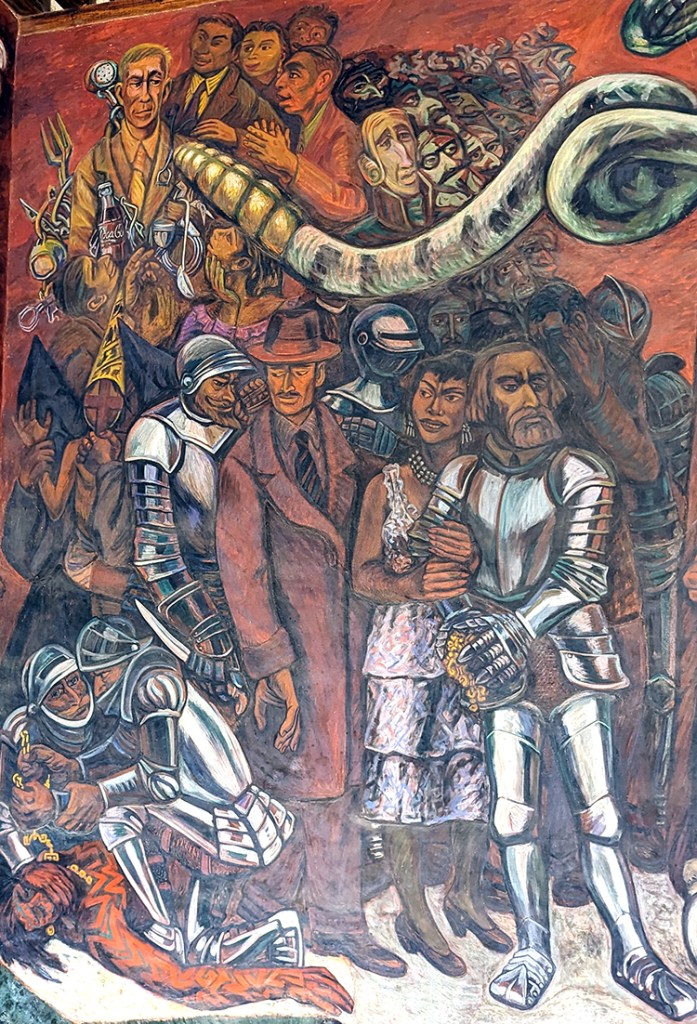

Above: Portion of “Defenders of National Integrity, Cuauhtemoc and History,” Alfredo Zalce, 1952, Museo Regional Michoacano Nicolas Leon Calderon

A Spanish Baroque house built in the 1700s is home to the Michoacan Regional Museum Dr. Nicolas Leon Calderon. With the oldest artifacts in the museum dating from more than 1000 years BC, the collection chronicles the history of and life in the state of Michoacan until hundreds of years after the dramatic impact of the Spanish Conquest.

Oh, Emperor Maximilian I (1832-1867) is said to have slept here (I believe this a more reliable claim than that of owners of almost every old house in central Virginia boasting “George Washington slept here.”). The home belonged to Francisca Roman de Malo and her husband when Maximilian stayed there in 1864 at the beginning of his brief reign. Francisca served as lady-in-waiting to Empress Carlota (1840-1927).

Above: An unusual hanging arch leads to the grand staircase of the Regional Museum.

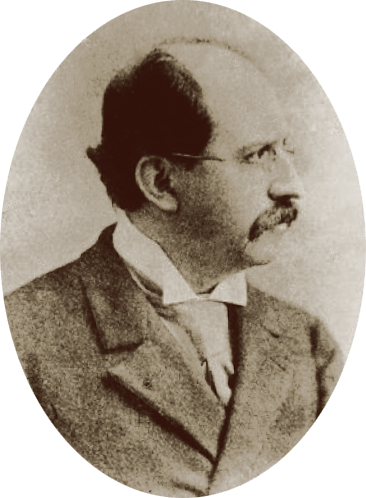

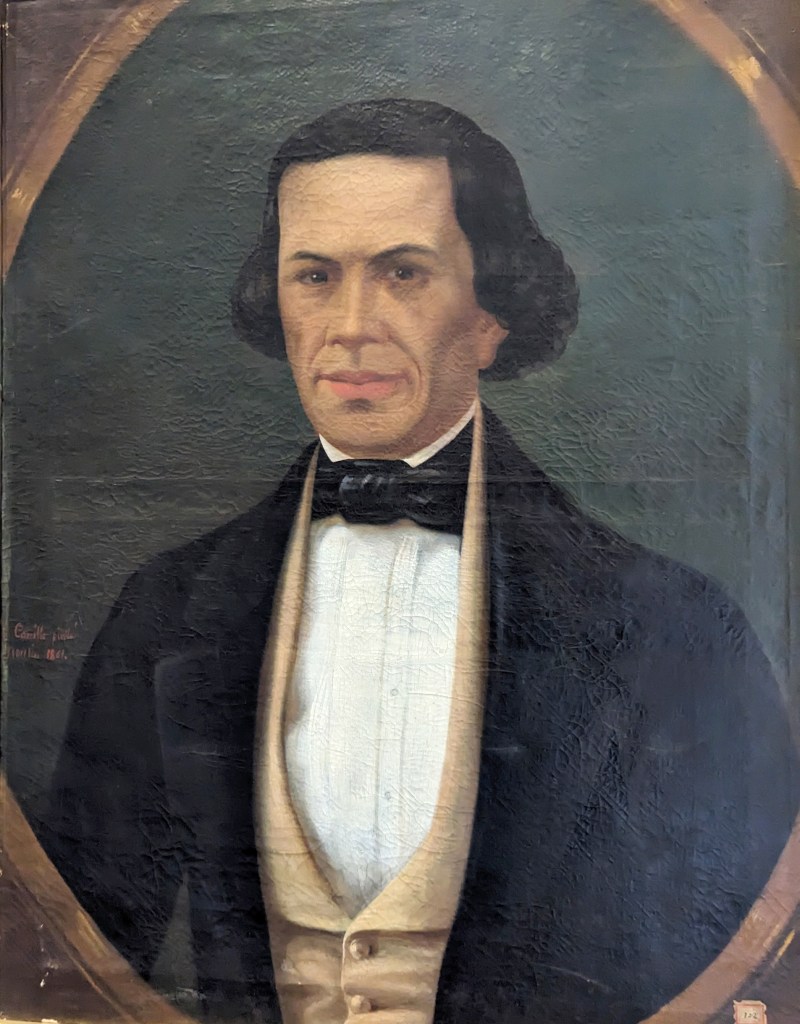

Established in 1886, the museum originally was located across the street on the campus of Colegio San Nicolas. It is named in honor of the first director of the museum, Nicolas Leon Calderon (1859-1929).

Launching a museum was far from the only assignment heaped upon the Renaissance-type man. At the time, the surgeon also was a professor of pathology and Latin at the colegio and was a director of both the Women’s Surgery and the Civil Hospital of the city. These represent only a few of the prestigious appointments he would hold in Morelia, Oaxaca and Mexico City during his lifetime. With encyclopedic knowledge in many fields, the doctor penned hundreds of printed works on subjects as diverse as pre-Columbian languages and ethnography, obstetrics, librarianship and botany.

Artist Diego Rivera praised the importance of an anonymous, 18-foot-wide painting, portions of which are pictured below, because of its details illustrating the racial and social stratifications of the time. Flanked by priests shielding them, normally cloistered nuns are captured by the artist in a major public procession as they relocate from a more remote convent to a new one near the Cathedral in 1738.

Above: Details of “The Transfer of the Dominican Nuns to Their New Convent in Valladolid,” 1738 (Note: Valladolid was the original Spanish name for the city of Morelia.)

The image on the left shows a small portion of the mural dominating the grand staircase in the museum. Patzcuaro-born artist, Alfredo Zalce Torres (1908-2003), was a founder of both the League of Sculptors and Revolutionary Artists and the Popular Graphic Workshop.

In this mural, he covers a broad swath of the history of Mexico and the people who influenced it. Unlike the painting above covering a specific point in time, Zalce jumbles together his subjects drawn from different eras. You have armored conquistadors represented in this frame as well as suited capitalists striving to conquer this part of the world with Coca-Cola.

I failed to locate any online explanations of who’s who. In the hope that someone more knowledgeable will set me straight via comment, I’m offering my probably incorrect interpretation of the three central figures in this detail of the mural. The armored one on the right is the conquistador Hernan Cortes (1485-1547). Then I’m wildly guessing the woman clutching his arm represents La Malinche (1500?- 1529?), updated in a pret-a-porter dress fashionable about 1950. And the big-handed man attired in a suit of the same period? Two hunches: the President of Mexico in 1952, Miguel Aleman Valdes (1900-1983); or perhaps the inclusion of a self-portrait of the artist himself.

This partial tour of the history of Michoacan via the museum needs one additional stop. There are always at least two sides to every war, and my exposure to the interpretation of “the United States 1847 invasion of Mexico” arrives mainly from El Norte.

According to the words carved into the San Jacinto Monument in Texas:

“Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican-American War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American Nation, nearly a million square miles of territory, changed sovereignty.“

To the people of Michoacan, then-Governor Melchor Ocampo (1814-1862) is heralded for his role in rallying its citizenry to contribute funds and to voluntarily enlist to fight against the illegal annexation of Texas. He organized 4,000 men to form the Matamoras Battalion to march in defense of Chapultepec Castle in 1847.

“…consider how much glory they expect, how many affections they leave, how great satisfaction it will be to return, to gather that and these. Children we are of our own works: fight tenaciously and you will win; wrest their favors from fortune; She has always granted them to the brave; Think that he does not die for a cause but the one who deserves the title of man.”

Governor Melchor Ocampo’s address to the Matamoras Battalion setting out for Mexico City to fight United States troops in 1847

Ocampo opposed the final settlement with the United States, but according to museum text:

“Mexico had exhausted its economic resources, the army was disorganized and without weapons, the ports were blocked. So when the peace proposals came, Mexico had no choice. On February 2, 1848, the Treaties of Guadalupe Hidalgo were signed by which Mexico definitively lost Texas; also the territories of New Mexico and Alta California, that is, more than half of its territory.”

Ocampo continued to play an active role in national politics and served in the administration of President Benito Juarez. He was kidnapped and executed by a firing squad in 1861.

The Mexican flipside in a nutshell: The 1847 war was a poorly cloaked land grab by El Norte. An exhibit we encountered in Chapultepec Palace several years ago includes an apologetic quotation from former President Ulysses S. Grant in which he terms it “a wicked war…. We had no claim on Mexico.”

Admitting a few “woke” thoughts of my own: At the time, the United States definitely was all gung-ho westward-ho, dreaming of “sea to shining sea.” If underlying root causes of this and the earlier Texas Revolution were allowed to be presented and freely analyzed in seventh-grade Texas history classes, including viewpoints from both sides of the border, our relationship with our southern neighbor might be considerably better.