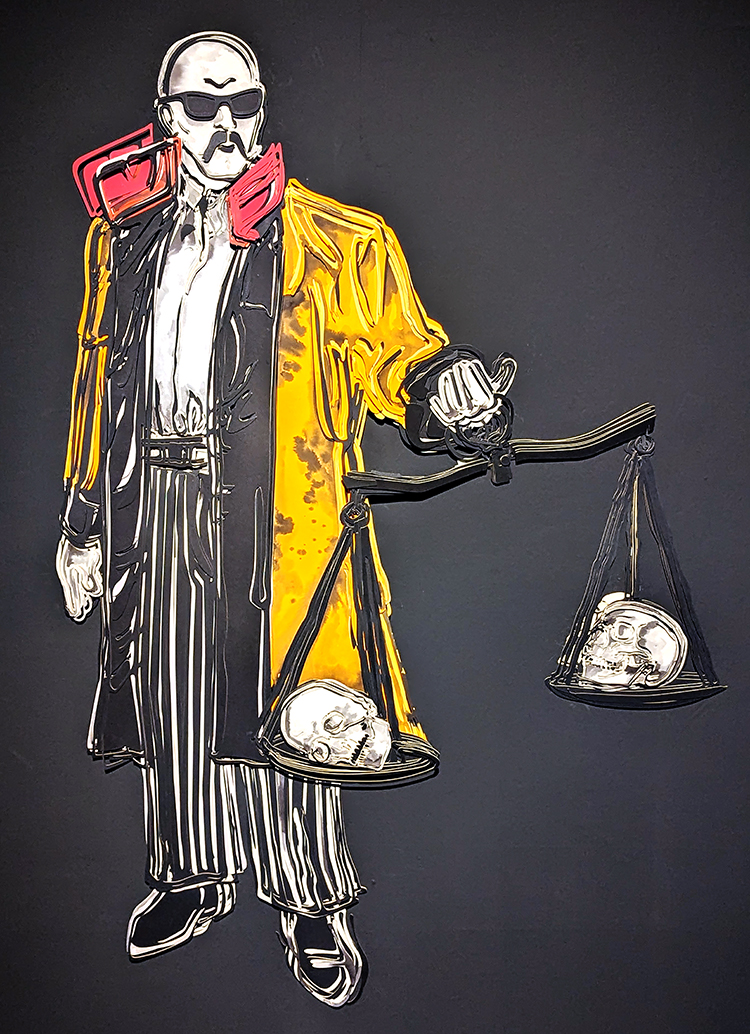

Above: “Femen/Kabatas,” Esra Carus, cardboard cutout, 2016

During a trip in Kabataş, a woman claimed that she and her baby were attacked by about ten half-naked men…. She held a demonstration on the balcony of a hotel in Paris…. It was impossible not to relate with the half-naked show of Femen girls….”

Esra Carus (1968-), Instagram (AI translation)

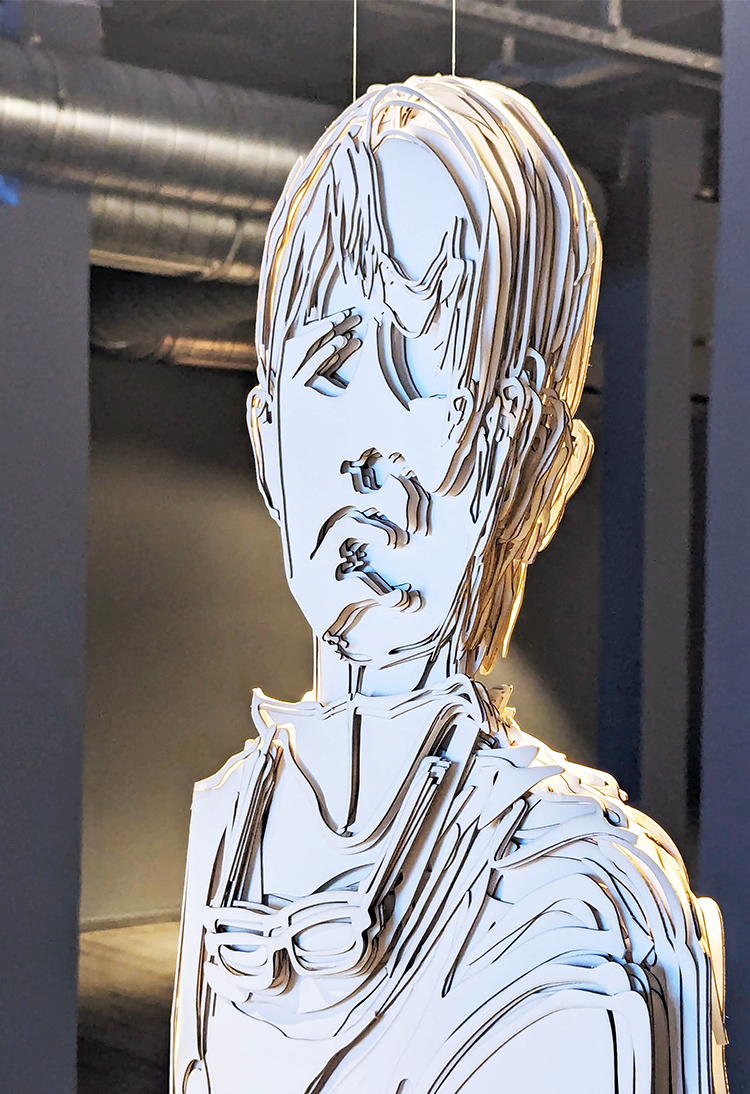

We wandered around the streets of the Tophane to Depo Istanbul without much of a clue about what art we’d encounter inside the former tobacco warehouse, renovated in 2008. We were met with “Yas. Yasa. Yasak,” or “Grief. Law. Prohibition,” and immediately were struck by strong, strident imagery.

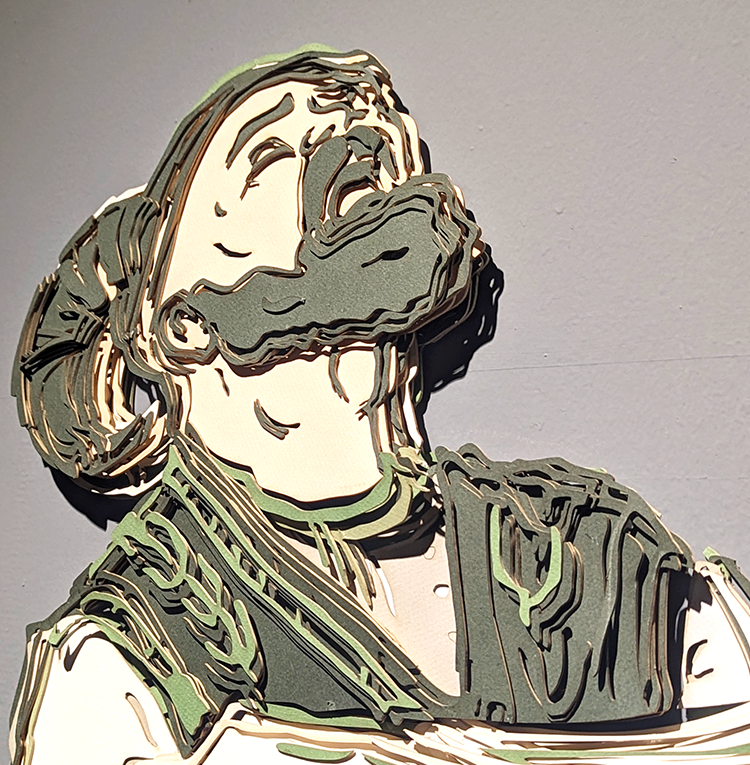

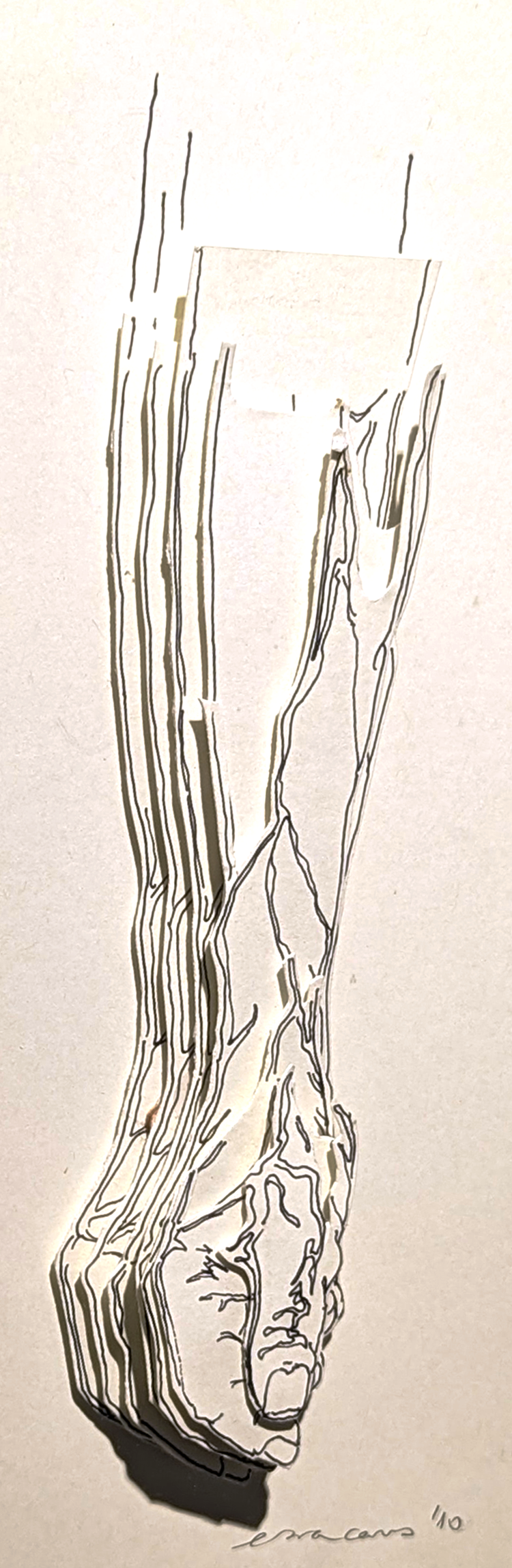

We were snapping photos left and right, when a smiling woman wearing a hijab approached us. She wanted to introduce us to the artist, Esra Carus, who happened to be present. It was hard to separate which thoughts were Carus’ and which were our enthusiastic translator’s, but societal wrongs – evil – and women’s rights were at the top of the list. While the exhibition was a 30-year retrospective of the artist’s work, all are applicable to current events.

…a process in which moral values collapse, the law disappears, deaths and destruction are ignored, and evil is normalized. We need to put all these common issues on the table in order to clean up the subconscious of society.”

Esra Carus, interviewed by Oslem Altunok, “A Personal Projection of Stacked Moments, of Shared Wounds,” Arganatlar (AI translation), July 1, 2024

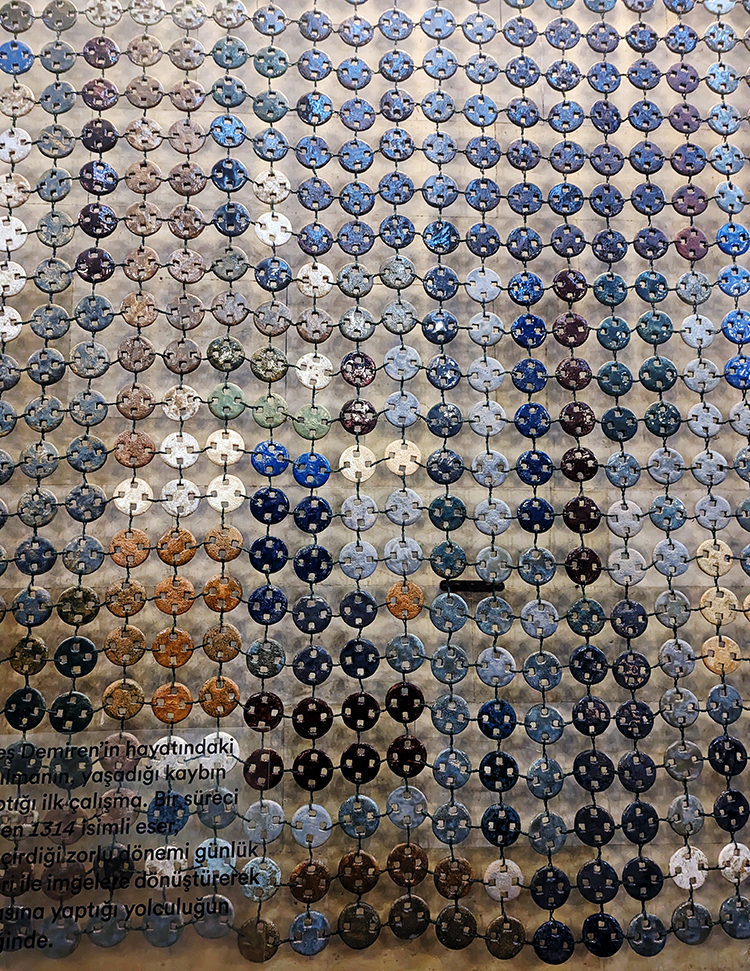

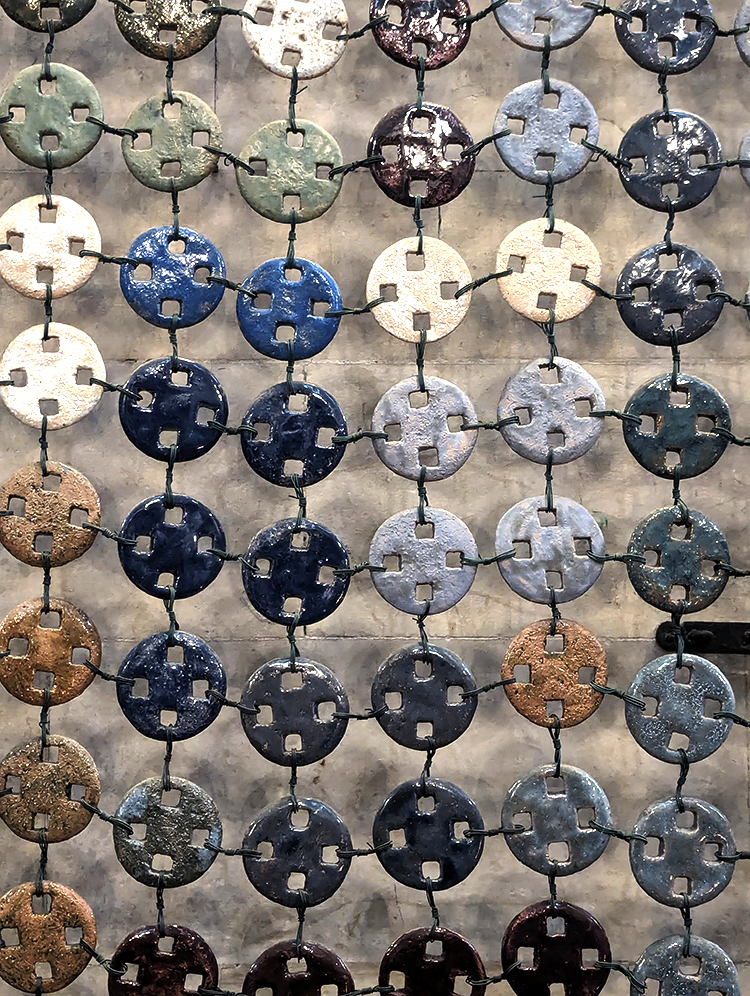

Above: Cardboard cutouts and ceramic works by Esra Carus from a retrospective exhibition at Depo Istanbul

Nearby, we came across a Victorian Gothic-style church, Crimean Memorial Christ Church. Construction of the 1868 church was commissioned by Sultan Abdulmecid (1823-1861) as a memorial to British soldiers who died during the Crimean War, 1853-1856. Today, the church assists displaced refugees, most recently Christians who have fled Pakistan.

The church was hosting an exhibition of quilts in familiar beautiful Amish-looking patterns, yet by a Turkish artist, Oya Erenli Sezer.

I accompanied my daughter Didem to Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania—in Amish country…. Intrigued, I started to research the Amish people, their art and their history. I learned that their patterns were based on daily life—building houses, plowing fields, growing food…. Patchwork design is actually common in Turkish culture. For example, patchwork prayer rugs are called kirkpare (“40 pieces” in Turkish). I’ve also seen Ottoman-era military tents made of patchwork because it’s easier to mend them in wartime.”

“From Kirkpare to Amish Quilts,” Oya Erenli Sezer

Above: Oya Erenli Sezer’s quilts exhibited in Crimea Memorial Christ Church

The Crimean War concluded with the 1861 Treaty of Paris, prohibiting Russia from basing warships in the Black Sea – as in Crimea. How do we once again ignore Russian transgressions upon its neighbors?

Today, there is a system that brings us face to face with all kinds of evil, increases the level of fear and feeds on it, causing us to close down more…. We have to understand the other person’s emotion; we have to be able to look at someone else’s pain. Because, as Arendt said, evil happens where there is no reasoning.”

Esra Carus, Arganatlar