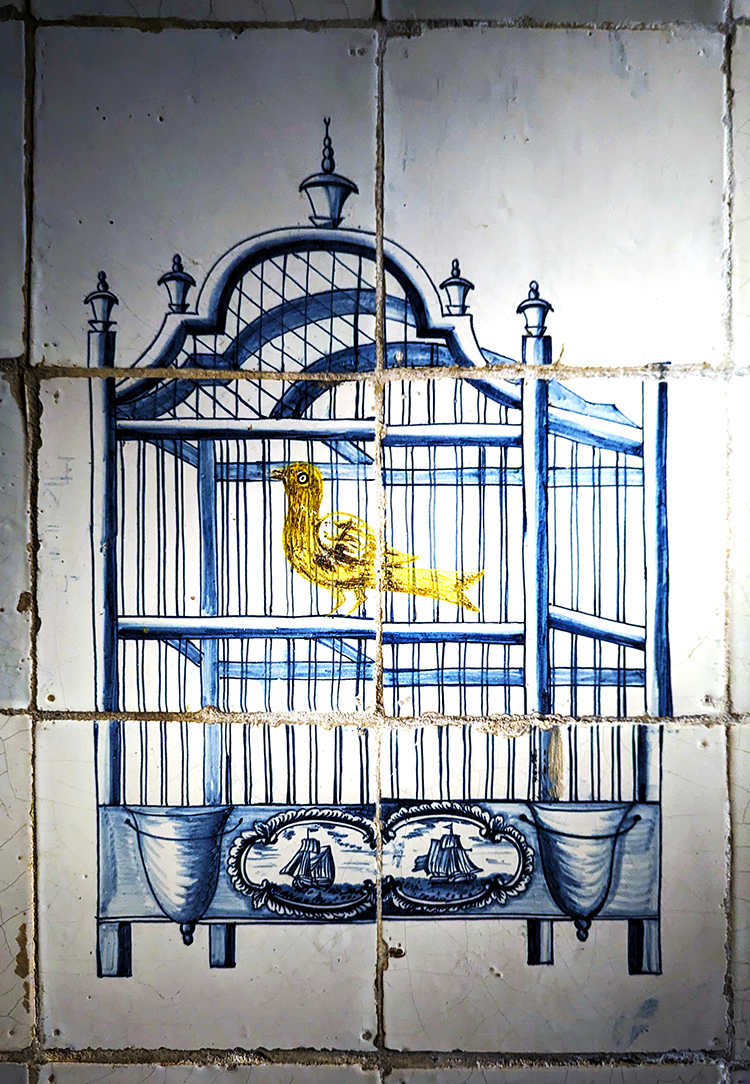

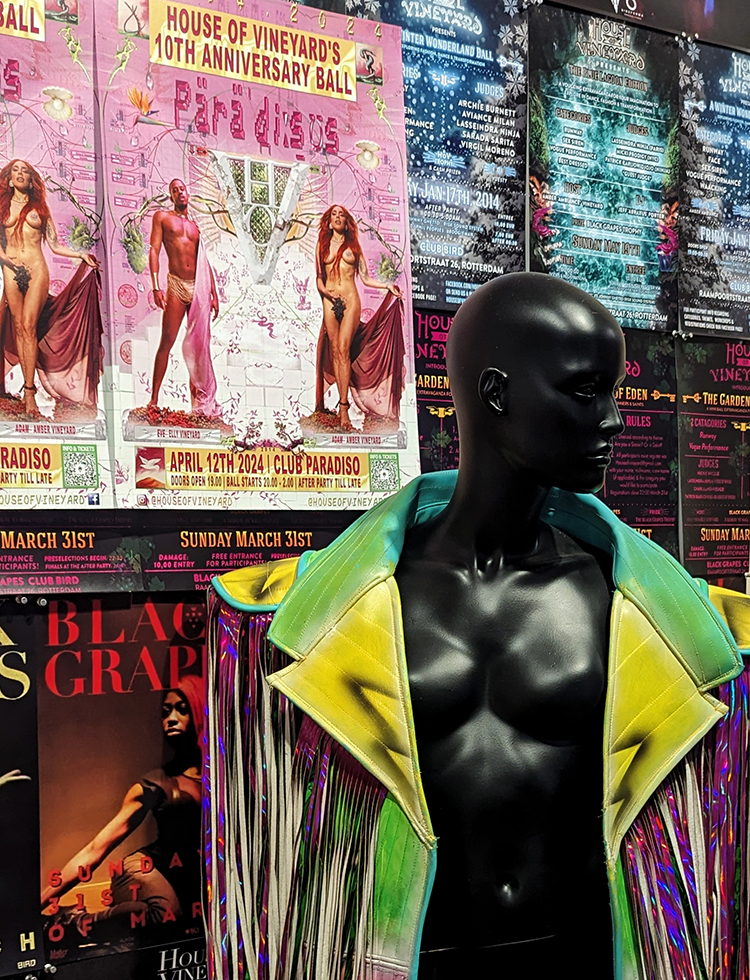

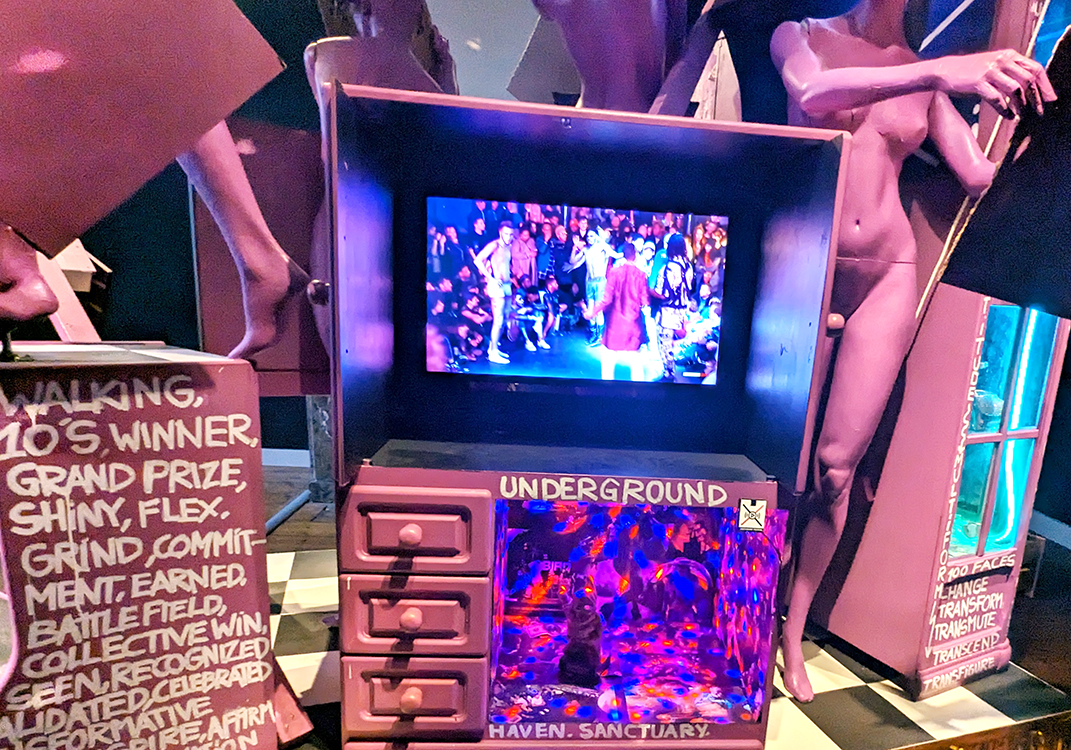

Above: House of Vineyard exhibition reacted and related to historic artifacts in the Abraham and Louisa Willet-Holthuysen House Museum.

Historically, the voices and experiences of Black and Brown femme queens have often been marginalized. But their resilience, courage, and unyielding spirit have paved the way for progress both off and on the runway…. In the dining room, we honor five queens who not only fought for a seat at the table, but created their own.”

House of Vineyard curator notes for temporary contemporary art exhibition

Keeping a house museum fresh, appealing and relevant to diverse audiences is extremely difficult, speaking as someone who had chaired a committee running one. I wish my visit to the Abraham and Louisa Willet-Holthuysen House Museum, a house built on the Herengracht Canal in 1685, had been years earlier.

Instead of keeping its collection static, the house museum stimulates repeat visitation by weaving thoughtfully curated contemporary art throughout its rooms. Often times, house museums are filled with gray-hairs, but not everyone there had our same color hair. The House of Vineyard’s “Grand March: A Historic House through a Ballroom Lens” attracted a diverse, youthful group. And it worked. All ages appeared interested in both the old and the new.

“Ballroom culture” emerged in the 1970s in Harlem, New York, as a space where African American and Latinx trans women and queer people could gather to express themselves freely, without fear of repercussions. The six-month residency at Willet-Holthuysen served as a celebration of the tenth year of the founding of the first House of Vineyard in the Netherlands.

We reimagine, repurpose, and intervene within the house – responding to the stories these rooms tell and claiming space for our own stories…. we engage in a dialogue between the fantasies of the original owners and the world as propositioned by the ballroom. We are shaking the room. This is our Grand March, a celebration of queerness, a testament to the enduring human spirit, and a tribute to those who refused to be invisible.”

House of Vineyard curator notes

Above: The Willet-Holthuysen House Museum

So what would the owner-occupant who entrusted this home and its contents to the city of Amsterdam in 1895 think? Based upon this visit, I speculate she would applaud.

Louisa Holthuysen (1824-1895) was the only child of a wealthy merchant family, a family traveling extensively throughout Europe. Her father would take her with him as he visited artists in their studios to expand his own collection, inspiring Louisa to do the same after his death.

Realizing she would inherit the house and need the knowledge to manage her own affairs, Pieter Holthuysen made sure his daughter acquired financial skills in addition to appreciating the arts. Louisa was in no rush to marry. Enjoying her independence, she traveled – always respectably with her female companion – and acquired additional art for her home.

When Louisa did wed at age 36, she was no trad wife. She insisted on a prenuptial agreement ensuring retention of her property and assets. Louisa allotted her husband a generous allowance of 4,000 guilders a year.

Although her husband, Abraham Willet (1825-1888), also was from a wealthy family, was well-educated and had never married, Louisa’s decision to keep a rein on the finances was a wise one. Bram, as he was called, inherited enough money to follow his passion – not pursuing law as expected but collecting art. Essentially living the life of a boulevardier in Paris.

Bram, who had his brother Dirk manage his fortune, liked to live well, and regularly got into financial trouble. Maurits described his friend as ‘good-natured, but a wasteful and a spendthrift, so he went bankrupt every two years….’ After his time as a student he visited Paris several times…. dressed like a dandy, and that he rented ‘magnificently furnished chambers’ in Paris…. He enjoyed the company of writers and poets, and also received female visitors.”

Abraham and Louisa Willet-Holthuysen: 19th-Century Collectors in Amsterdam, Bert Vreeken, 2015

What goes on behind bedroom doors of others should be none of our business. However in the mid-1800s, a woman remaining single until age 36 would most certainly have been “suspect.” Back then, male gaydar must have been unreliable, as men wore frock coats with abundant frills. Obviously, this had been true for more than a century, as illustrated by the jaunty poses of the Cavaliers in the paintings above with their hands perched on hips and flaunting their lacey collars and cuffs. By today’s standards, those styles could not have appeared more gay.

The tastes of the newlyweds seem well-matched. They filled their home in the au-courant neo-Louis XVI style, traveling to Paris to import the furniture, chandeliers and wallpapers for their salon. The well-appointed room became widely known in social circles for its concerts, lectures and masquerade balls. In traditional Amsterdam, their parties were sedate compared to the more Bohemian hospitality they extended in their second home on the outskirts of Paris.

While the house museum’s holdings all seem antique to us now, it should be remembered they were cutting-edge at the time. The couple would frequently invite others to see their most recent contemporary acquisitions. In other words, to suit this couple’s tastes, the collection need not be frozen in time.

The pair embraced the “new.” And they certainly welcomed spirited creatives into their homes. The Vineyard’s exhibition envisioning what to wear to a ball in this house seems on target. Why not combine an armor vest with a full Victorian skirt?

If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.”

Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005)