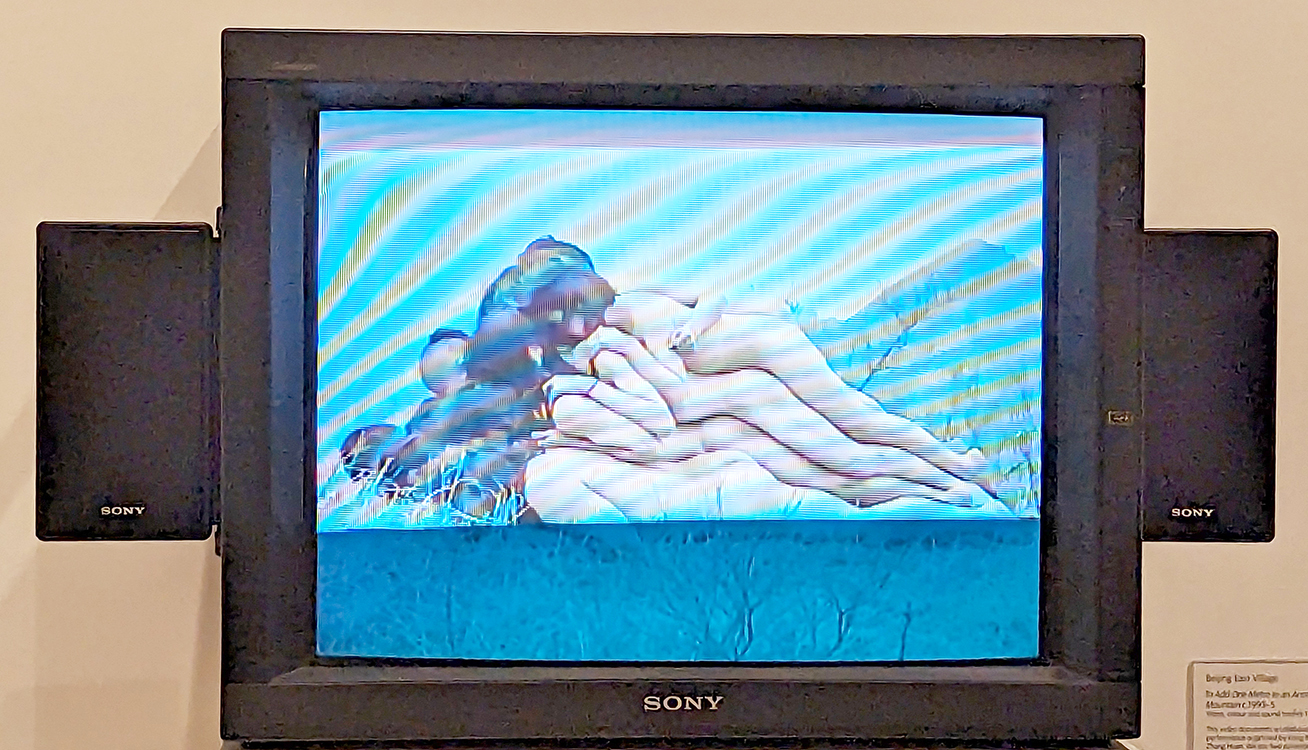

Above: “Life in His Mouth, Death Cradles Her Arm,” Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, 2016. Photo grab from video.

Architectural Challenge Number One, 1940s: Design an industrial complex on a site directly across the Thames from one of London’s most cherished landmarks – Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott (1880-1960) was an accomplished architect by the time he was tapped to tackle the Bankside Power Station. Unlike his earlier two-chimneyed Battersea Power Station, Bankside featured a single soaring chimney front and center, prompting some to refer to it as the cathedral of industry.

Architectural Challenge Number 2, 1990s: Convert a massive decommissioned power station into a frame for modern art. An international competition attracted 168 submissions, with the Swiss architectural firm of Herzog & de Meuron selected for the adaptive reuse project. The firm’s respect for and desire to preserve the external features of the brick power station impressed the selection committee of the Tate Modern.

Exposed steel framework reflects its industrial past. The former turbine hall of the structure functions as an enormous courtyard, more than 100 feet in height and close to 500 feet in length. The once-belching chimney serves as a handsome invitation to explore the art within.

Jacques Herzog: The ideal museum should be inviting, offer places to hang out, to meet people. The galleries should be diverse in size, proportions, lighting conditions, materiality.

…architecture and urban planning shape the identity of a place…. We seek to foster the public life it could and should generate. All architecture is public, and all architecture is political, because it is relevant to life in a community.

Accepting the architectural invitation, it’s time to move on to the art housed within the Tate Modern. The curators’ insights into works by artists with whom I was unfamiliar proved invaluable to my interpretation and understanding. Most of this post shares excerpts from the labels prepared by these experts.

The still shot featured at the top of this post is from “Life in His Mouth, Death Cradles Her Arm.” According to the museum label, it:

…is a single-channel video with sound of a performance by Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa. Lasting just under six minutes, it shows the artist holding a bundle wrapped in a shawl or shroud as he stands still in the passageway between the high wall-graves of the General Cemetery in Guatemala City…. it becomes apparent that the artist is holding a block of ice which gradually melts to create a small puddle between his feet…. The work was a reflection on the death of the artist’s brother and the high mortality rate of children in Guatemala as a result of the civil war (1960–96), with the artist explaining that he wanted to create a “blanket that could weep.”

Above: “Room for Asylum Seeker,” plastic, Siah Armajani, 2017.

Siah Armajani’s truck is from his “Seven Rooms of Hospitality:”

…a series of 3D-printed models about the conditions endured by migrants and refugees. The works explore the precarious spaces which refugees, exiles and deportees are forced to inhabit. Armajani made them in response to an incident in August 2015, when 71 people seeking asylum from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan suffocated in the back of a lorry abandoned on an Austrian motorway.

Above left: “Deification of a Soldier,” Yamashita Kikuji, 1967. Above right: “Winged Being,” Jean Arp, 1951.

The title of this work (above left) suggests that a soldier is being worshipped as if they were a god. However, the imagery is chaotic and violent…. It captures the absurdity of war. Yamashita made this painting at the height of the Vietnam War… protested extensively in Japan. It also reflects Yamashita’s traumatic memories of the Second World War. As a conscript in the Imperial Japanese Army, he witnessed many atrocities and took part in the killing of a Chinese prisoner.

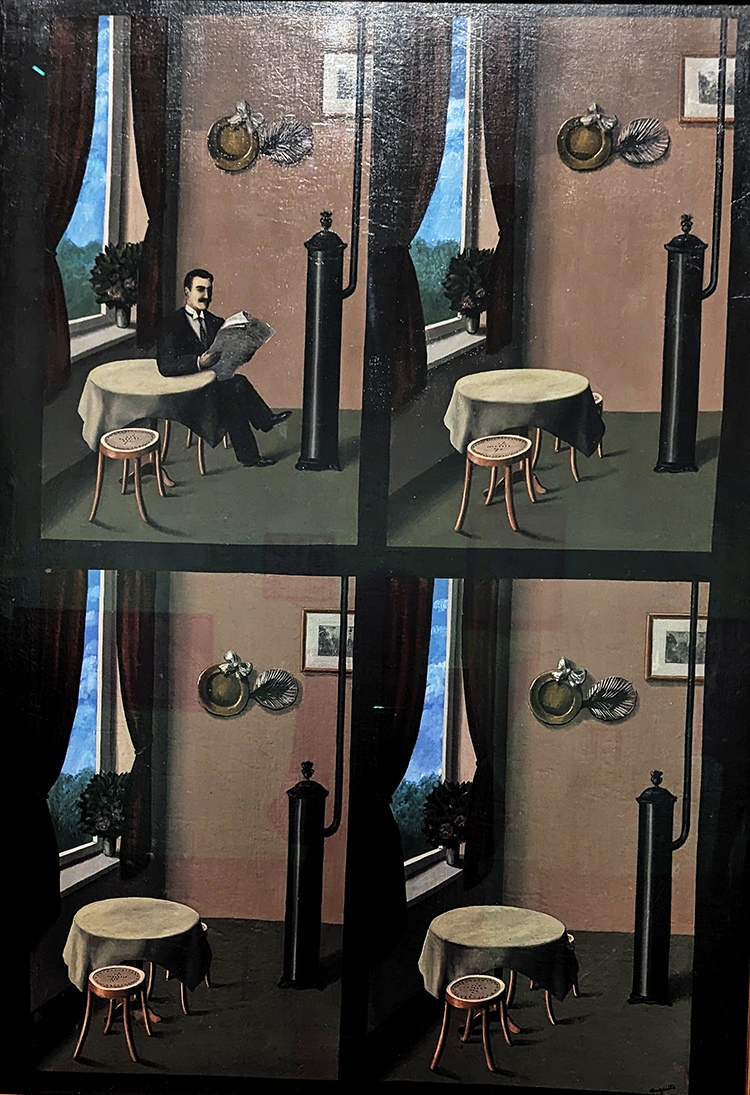

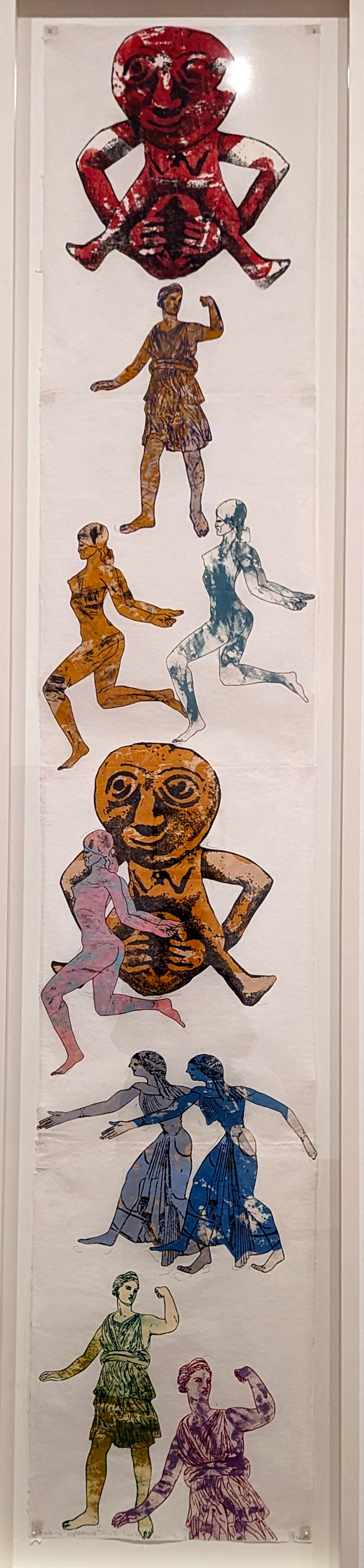

Above left: “Man with a Newspaper,” 1928, Rene Magritte. Above middle: “Mti,” Betye Saar, 1973. Above right: “Sheela-na-gig/Artemis: Totem I,” Nancy Spero, 1985.

In Magritte’s “Man with a Newspaper,” the four panels:

…seem to be indistinguishable apart from the disappearance of the man of the title…. This subtle undermining of the everyday was characteristic of Magritte and his Belgian Surrealist colleagues, who preferred quiet subversion over public action.

Involved in the American Black Arts Movement, Betye Saar’s altar-like assemblage, “Mti:”

…reveals the artist’s interest in ancestral history, ritual objects and their spiritual power. In the work Saar turns a Black doll into a religious icon.

Nancy Spero’s handprinted ink totem:

…features powerful female archetypes from across history, including the Sheela-na-gig, the Celtic goddess of fertility and destruction… and Artemis, the Greek goddess of hunting, childbirth and the moon.

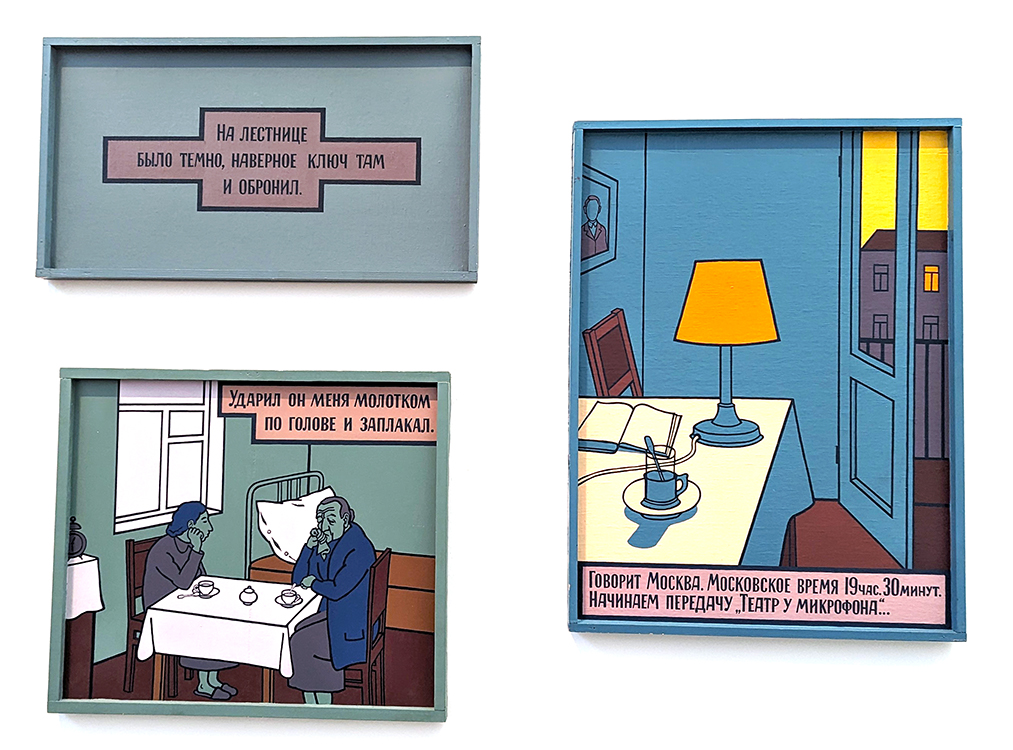

Above left: From a series of 35 paintings, “Apartment 22.” Three enamel on canvas works by Viktor Pivovarov – “It Was Dark on the Stairs,” 1994; “He Hit Me with a Hammer and Burst into Tears,” 1992; and “This is Radio Moscow….,” 1992. Above right: “Blue Purple Tilt,” Jenny Holzer, 2007.

With more v’s than any name I’ve ever typed:

Pivovarov was one of the founders of “Moscow Conceptualism,” an underground art movement that emerged in the USSR in the 1960s….The style and use of words reflects Pivovarov’s official career as an illustrator of children’s books, but the series exposes the underlying mechanisms of Soviet society…. Together the paintings deal with the everyday experience of enforced communal living and reflect the boredom, loneliness and violence excluded from official depictions of Soviet life.

Above left: “The Acrobat and His Partner,” 1948; and above right: “Two Women Holding Flowers,” 1954, by Fernand Leger.

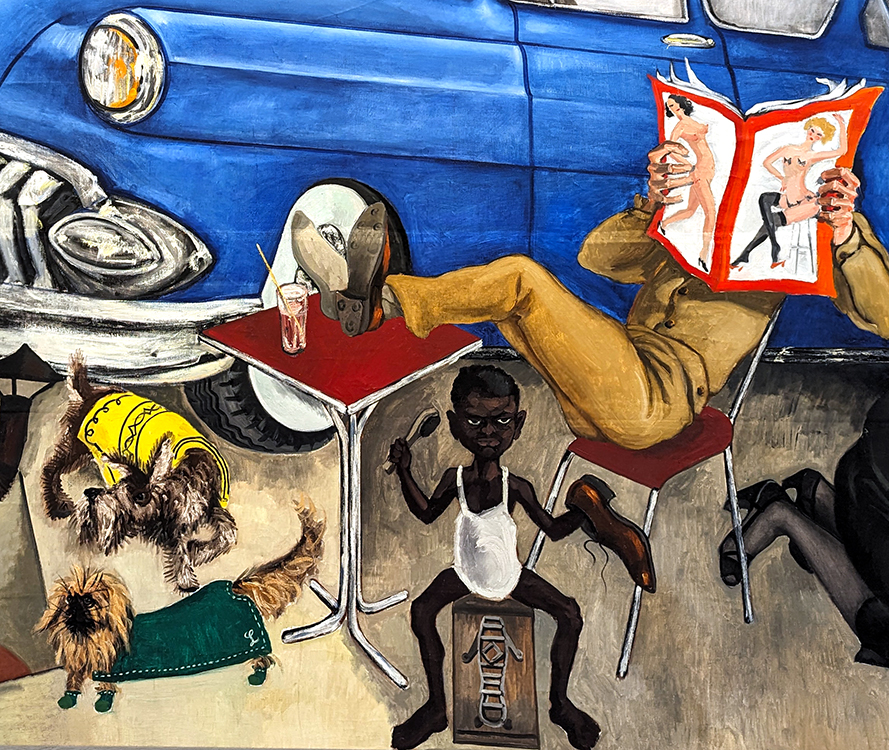

Above: “Atlantic Civilization,” Andre Fougeron, 1953.

Fougeron intended this work… to be an unsettling image. He uses harsh caricatures and stereotypes to criticize the Americanization of Europe. A businessman representing France greets a US car, symbolizing capitalism. His appearance is an antisemitic stereotype…. The artist depicts the US soldier reading pornographic magazines, a Black child shining shoes, and Algerian refugees sheltering under corrugated iron to condemn US global power, the exploitation of the underprivileged, and French colonialism in Africa.

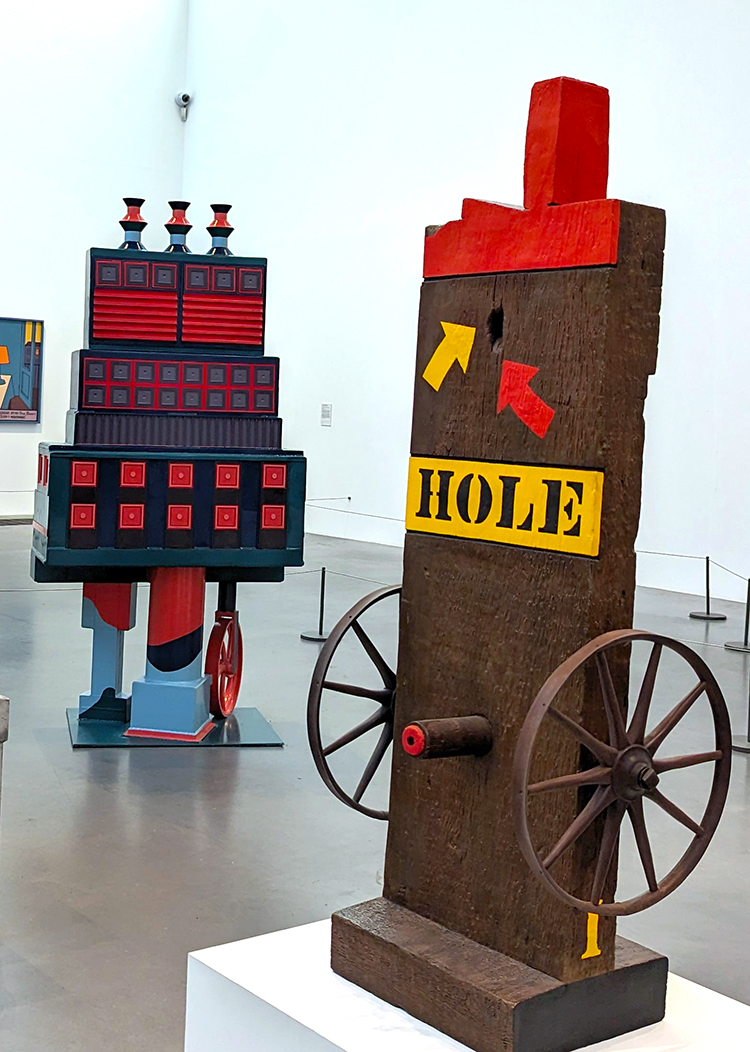

Above left: “Mechaniks Bench,” industrial collage, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, 1963. Above right photo, on left, “The City of the Circle and the Square,” industrial collage, Paolozzi, 1963; on right, “Hole,” Robert Indiana, 1962.

From the museum label for “Mechaniks Bench:”

Paolozzi began making machine-like structures in the early 1960s. He… wanted to eliminate “arty” qualities from his work. Instead he aimed for an impersonal, engineered feel…. He described his raw materials as “things that nobody would give a second glance… Part of the battle is to try, and resolve these anonymous materials into… a poetic idea.”

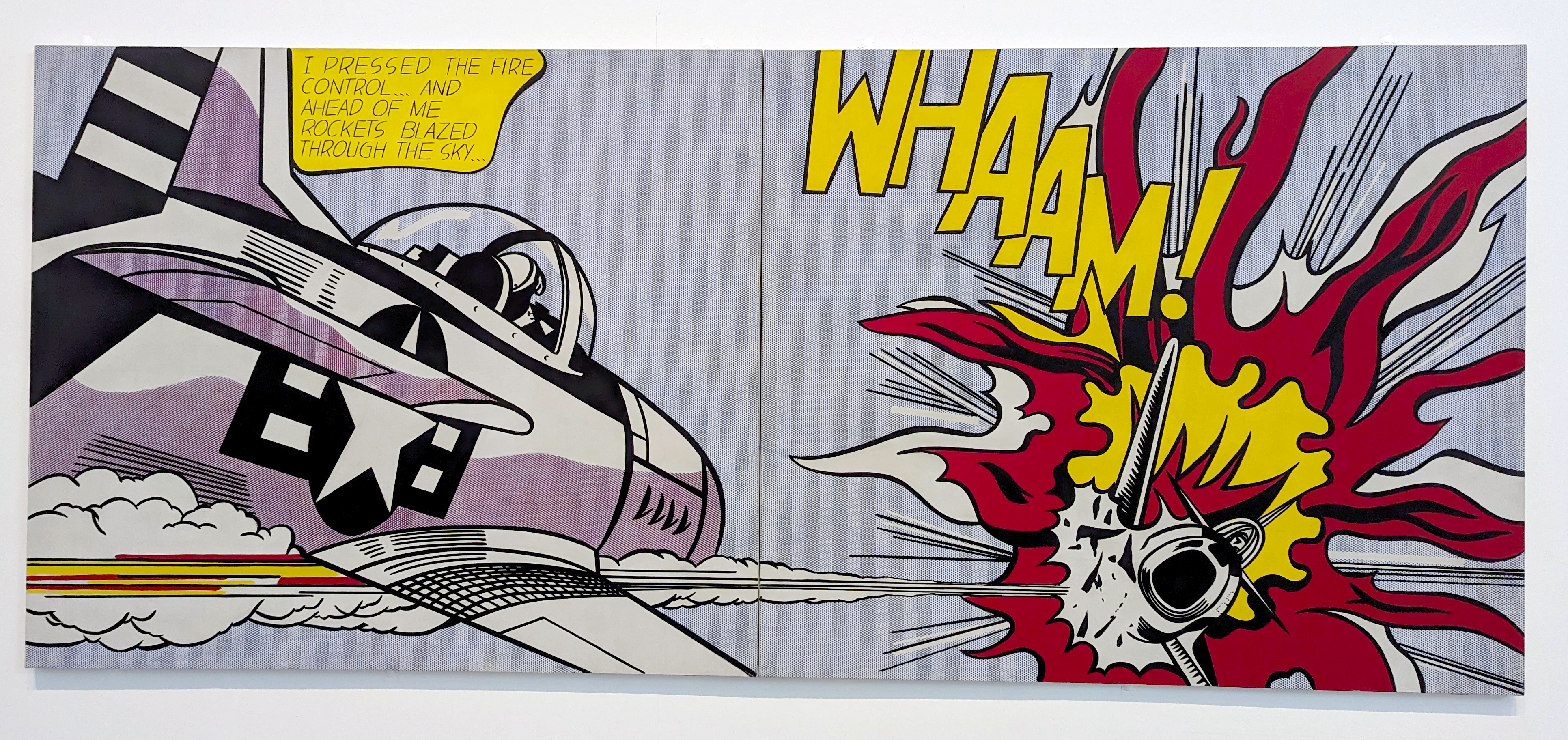

Above left: “Reflection on The Scream,” 1990. Above right: “Whaam!,” 1993, both by Roy Lichtenstein.

Above: “Babel,” Cildo Meireles, 2001.

Meireles refers to “Babel” as a “tower of incomprehension.” Comprising hundreds of radios, each tuned to a different station, the sculpture relates to the biblical story of the Tower of Babel, a tower tall enough to reach the heavens. God was offended by this structure, and caused the builders to speak in different languages. No longer able to understand one another, they became divided and scattered across the earth, and so began all mankind’s conflicts…. The noise produced by “Babel” is constant, but the precise mix of broadcast voices and music is always changing, so that no two experiences of this work are ever the same.

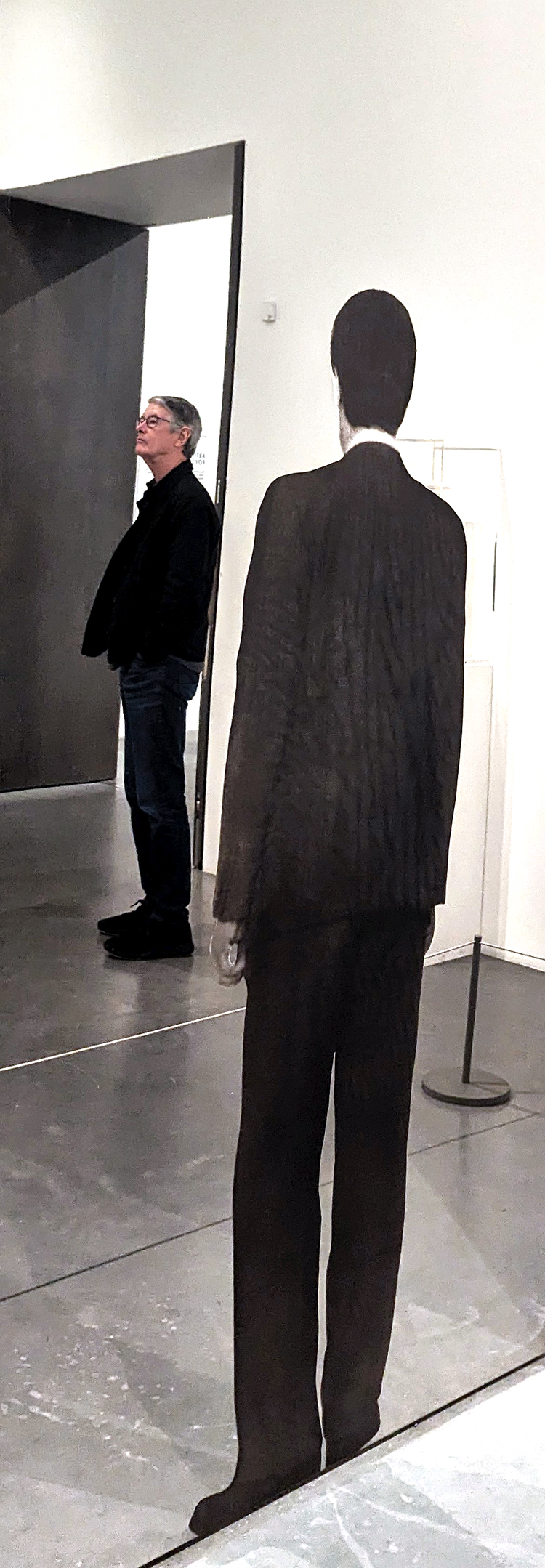

Above left: Suspended mirrors, Edward Krasinski; Above right: “Standing Man,” Michelangelo Pistoletto, 1962. Both photographs employ my randomly selected museum visitor to interact with the art.

From the museum label for Krasinski’s installation:

Edward Krasiński used tonal colour, lighting, photography and reflective surfaces to challenge the fixed nature of sculpture…. Krasiński transformed galleries into maze-like spaces through the use of cleverly positioned plinths, hanging objects and blue adhesive tape…. It integrates the mirrors with their surroundings, erasing the difference between real and reflected space.

Similarly in Pistoletto’s mirror painting:

The mirror allows each viewer to momentarily become part of the artwork, uniting time that passes for us with time that stands still for the man.

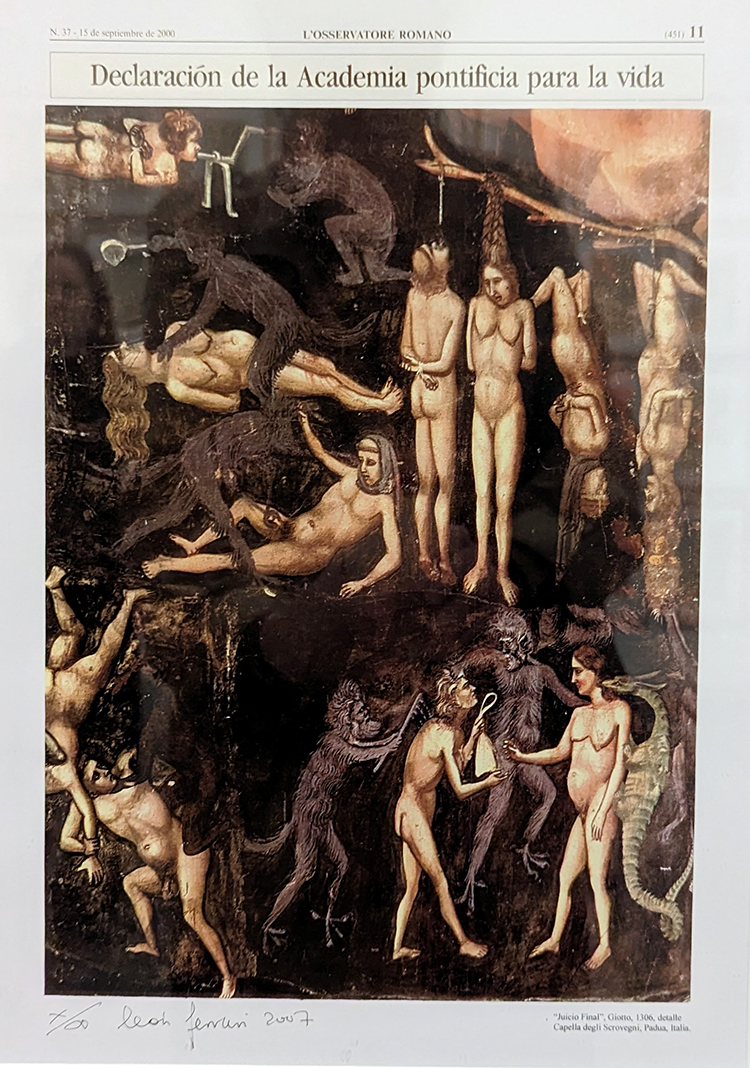

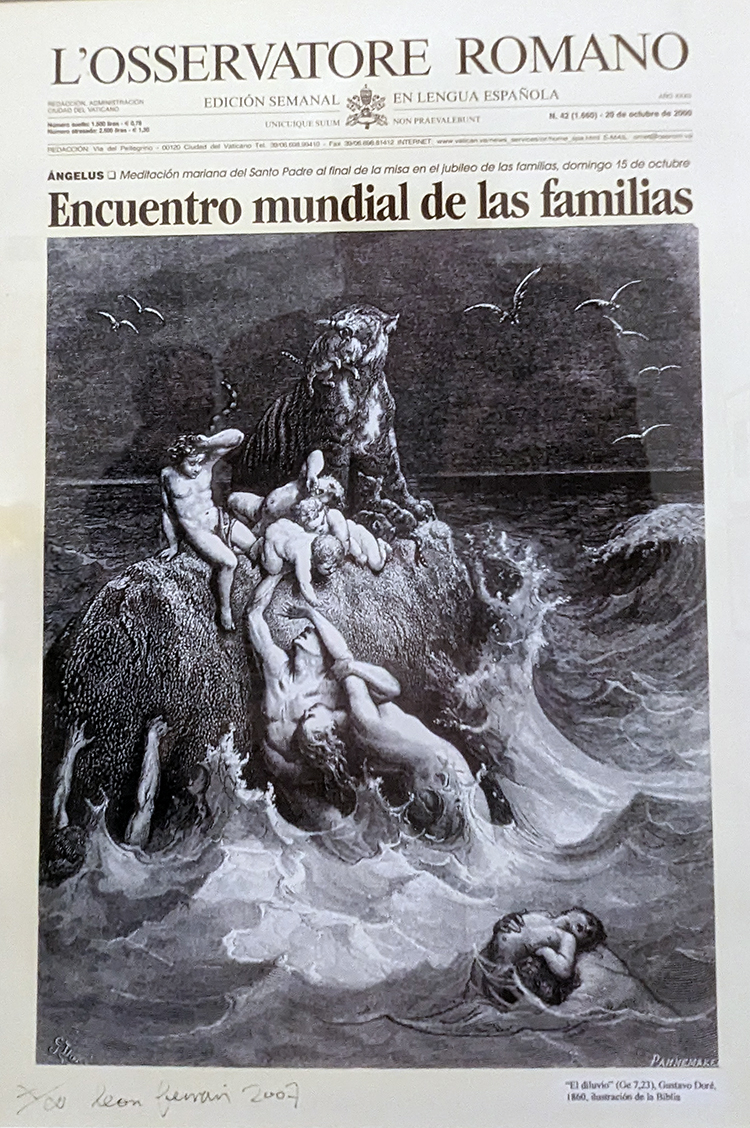

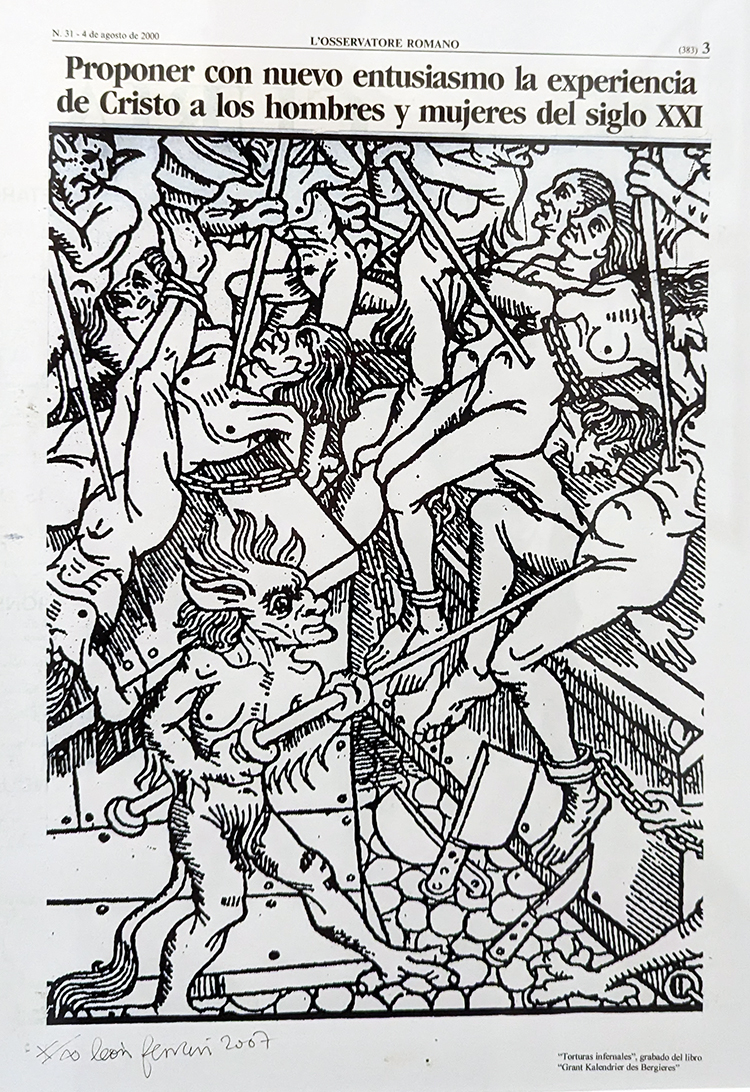

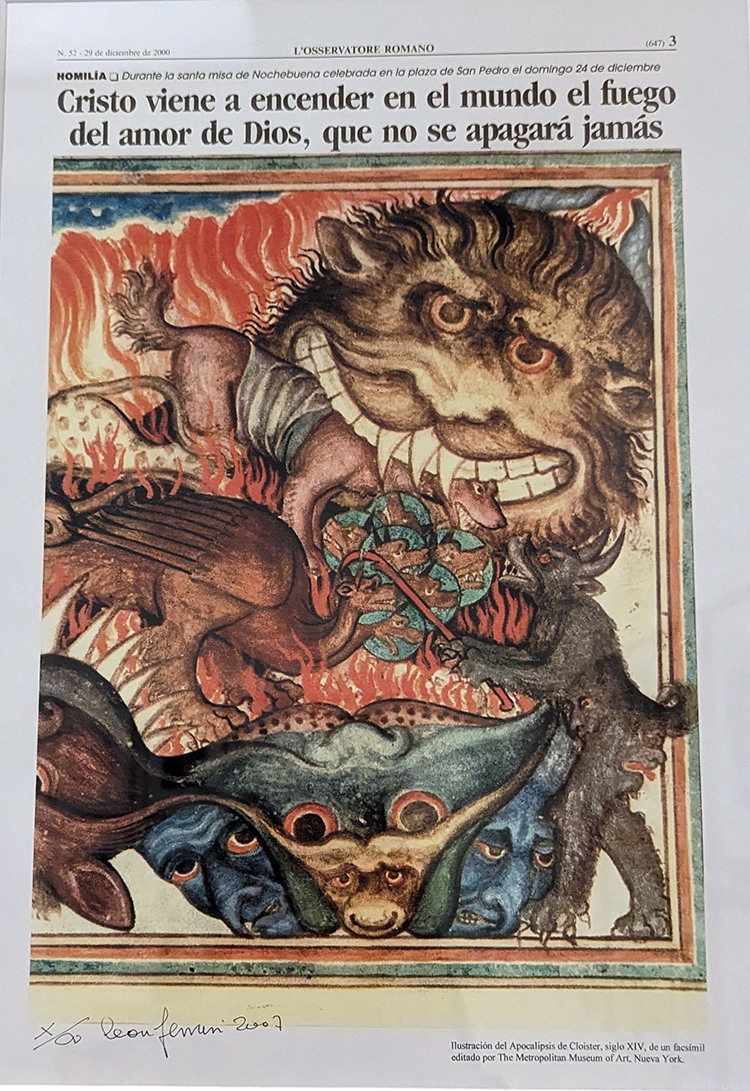

Above: 2001 collages, later photocopied, Leon Ferrari.

“Art is not beauty or novelty, art is effectiveness and disruption,” Ferrari wrote. Throughout his career he used his art to draw attention to state-sponsored crimes and censorship. He often criticized the Argentine government and the Catholic Church for their human rights abuses. In 1976, a right-wing military dictatorship seized power in Argentina. Due to his political stance, Ferrari and his family were forced to flee to Brazil. His son, Ariel, was one of the many citizens abducted by the military. His whereabouts remain unknown and he is presumed to be dead…. The works in this room are based on newspaper and magazine extracts. Ferrari would cut them out, sometimes add his own drawings or collage, and photocopy them. Ferrari’s reworking of religious imagery led to controversy. In 2004, Pope Francis—then Archbishop of Buenos Aires—called his art blasphemous. He demanded that an exhibition of Ferrari’s work should be closed.

Above left: “Portrait of an Artist in Crisis,” Tetsumi Kudo, 1980-81. Above right: Untitled, Jannis Kounellis.

From the museum label for Kudo’s “Portrait,” the assemblage:

… takes the form of a mass-produced animal cage painted a lurid green, inside which are the disembodied face and hands of a man rendered in wax. In the figure’s right hand are two paint brushes; the left hand grips a scatological form. Four smaller wire cages are suspended from the ceiling of the main structure. These contain, respectively, the small painted maquettes of a grey mouse, a yellow canary, a red heart and a yellow phallus….

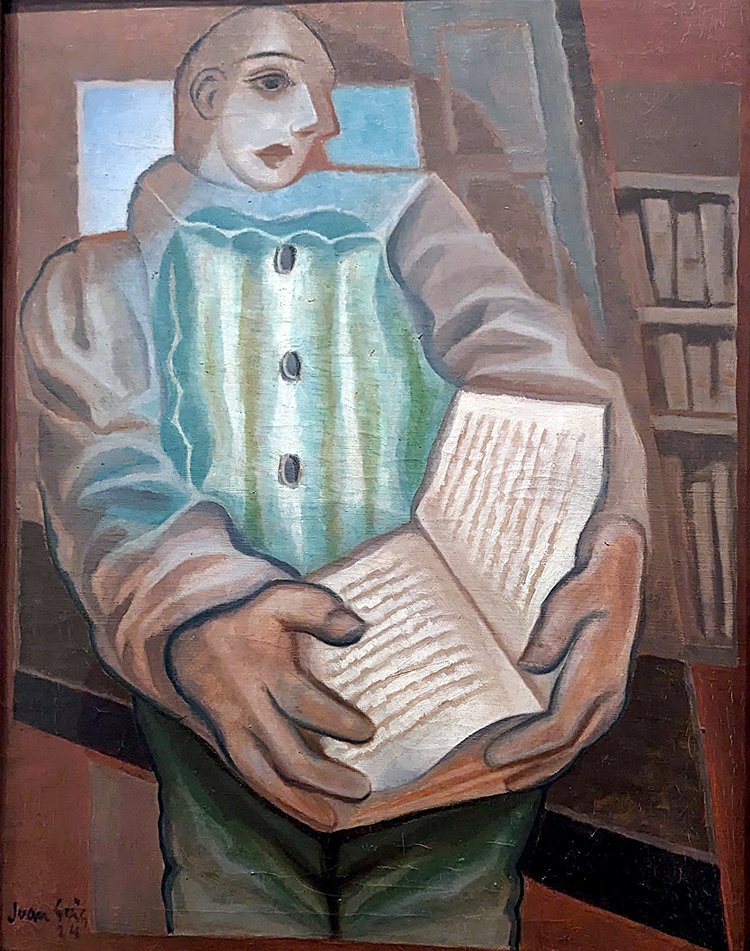

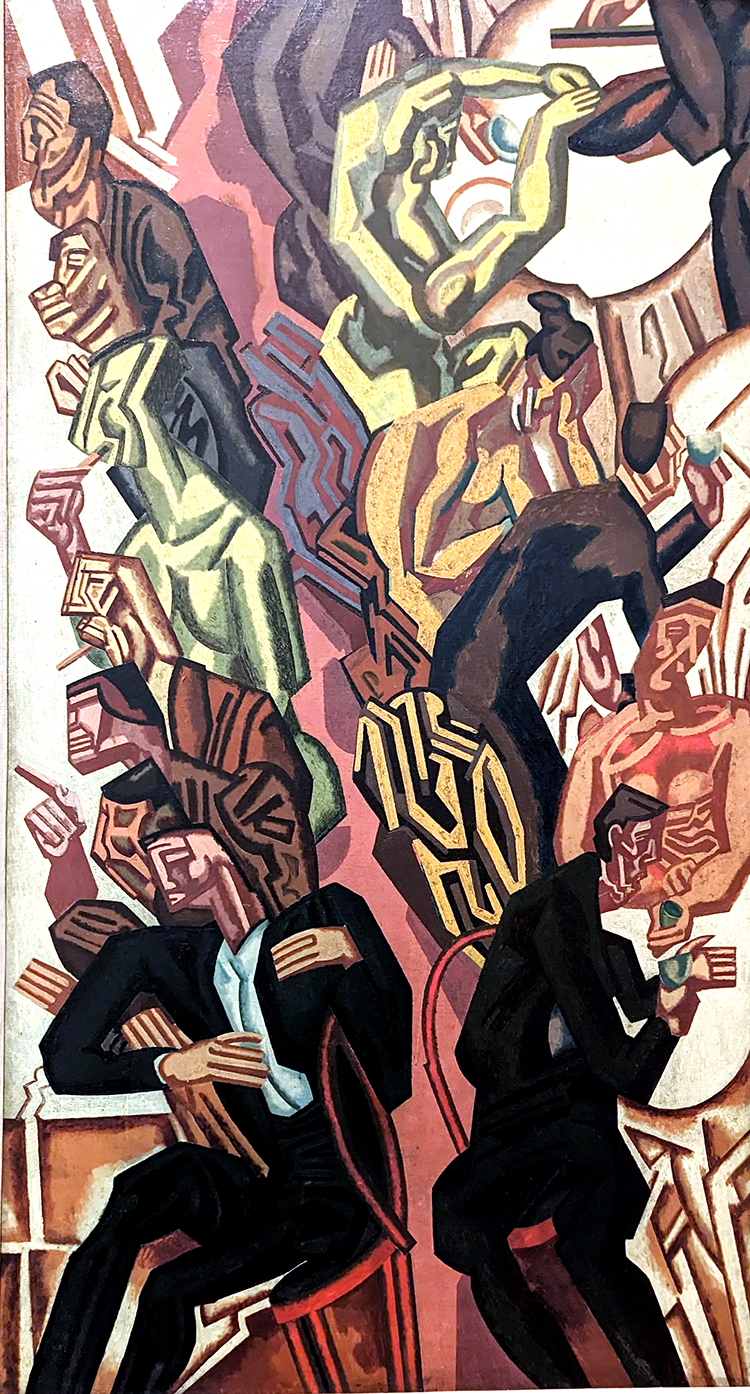

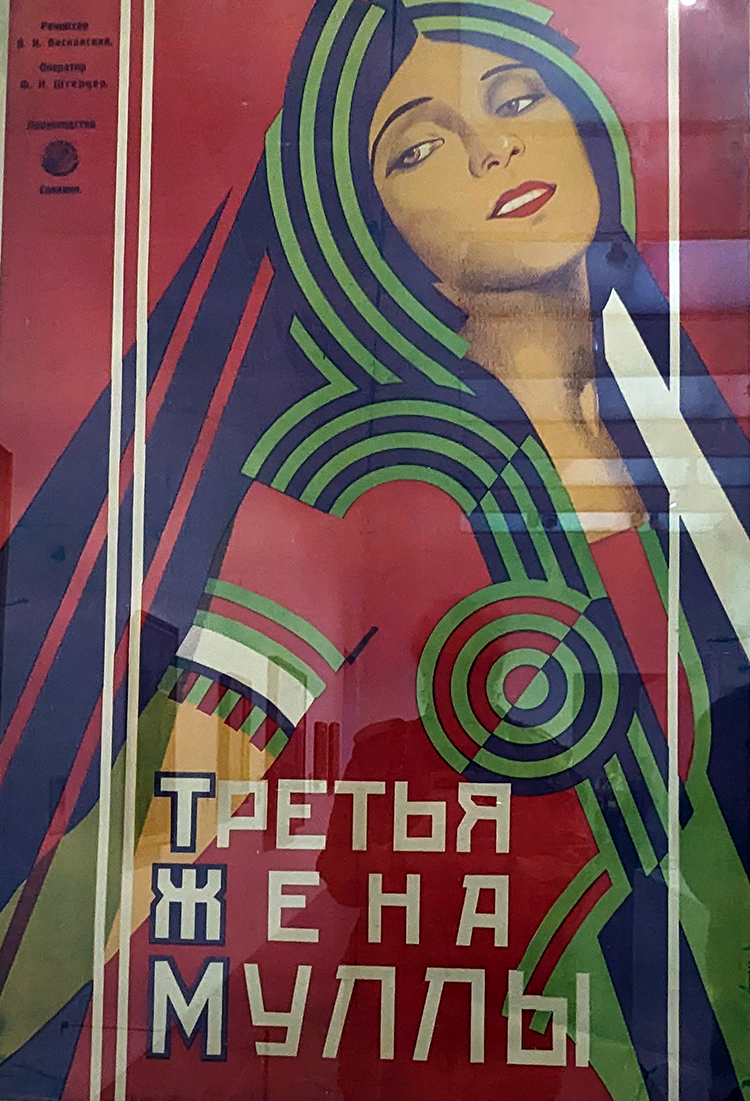

Above left: “Pierrot with Book,” Juan Gris, 1924. Above center: “The Diners,” William Roberts, 1919. Above right: “The Mullah’s Third Wife,” Iosif Gerrasimovich, lithograph, 1928.

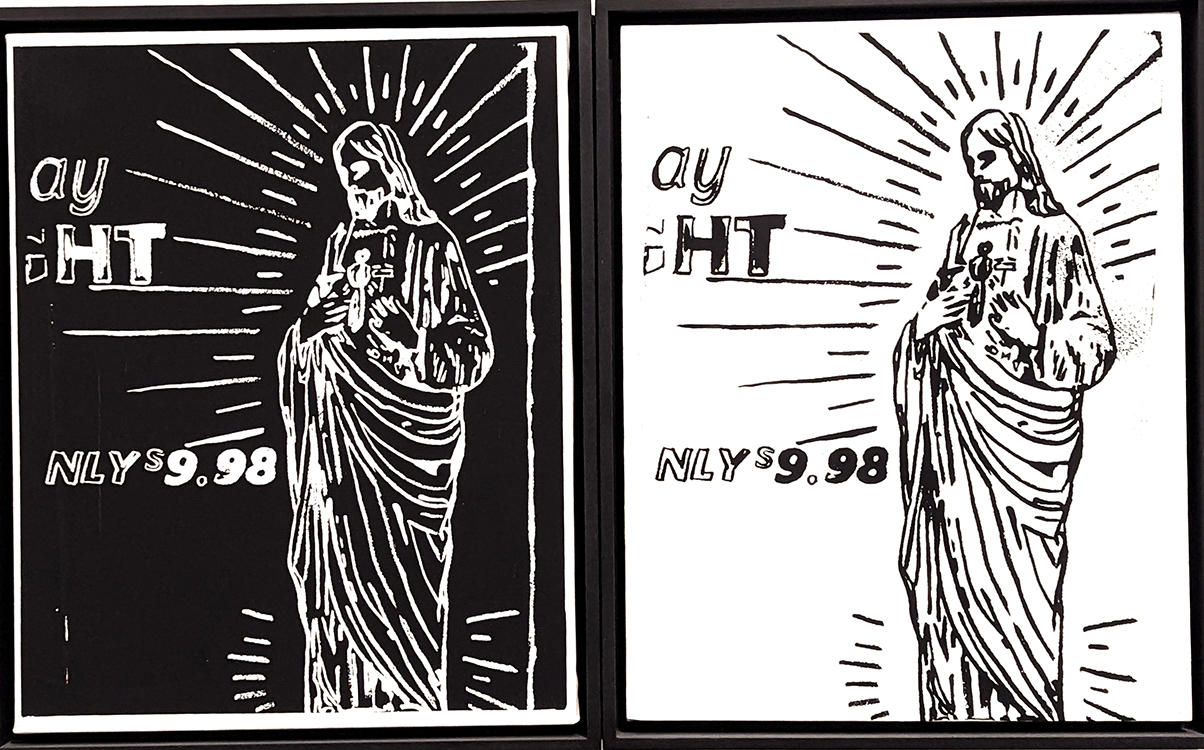

Above left: “Christ $9.98,” Andy Warhol, 1985-6. Above right: Untitled, Jannis Kounellis, 1979.

… Warhol was devoutly Catholic and was raised surrounded by religious iconography. This image of Christ relates to this theme but also the positive/negative aspect of to the diptych can be seen as echoing the Cold War conflict.

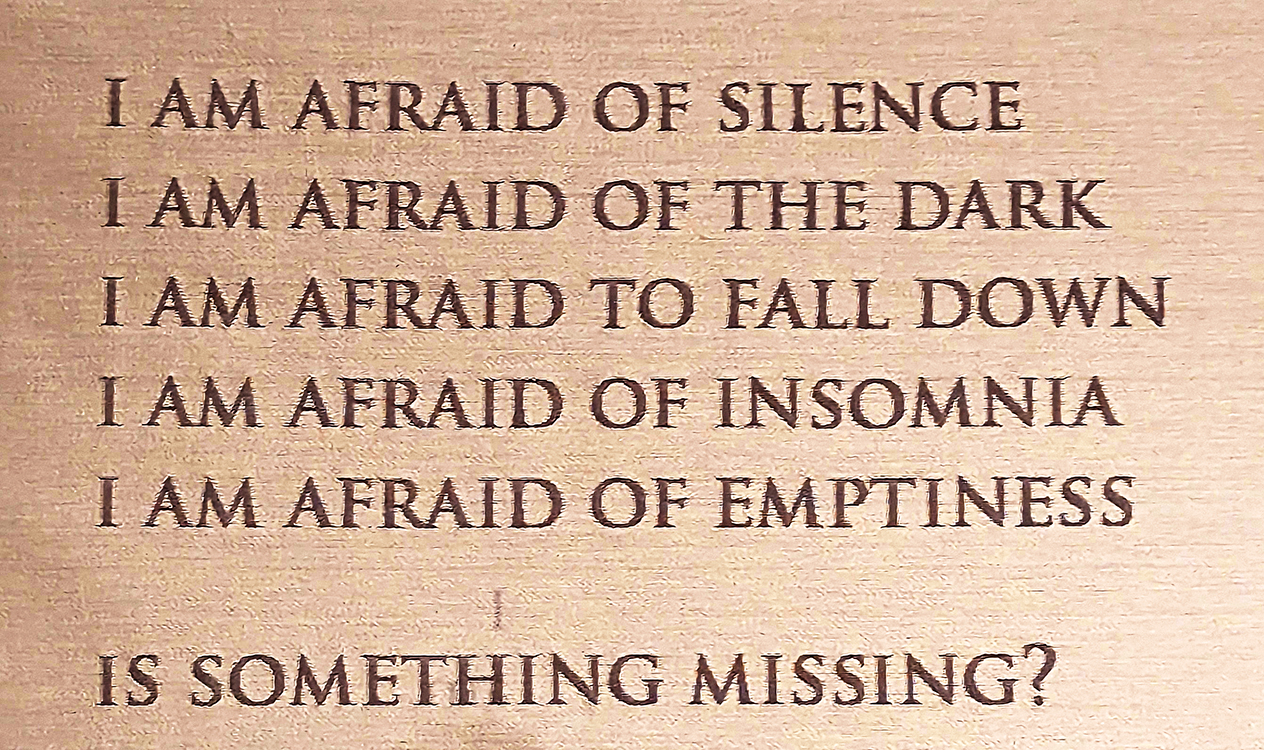

Above: Mounted woven fabrics, Louise Bourgeois, 2009.

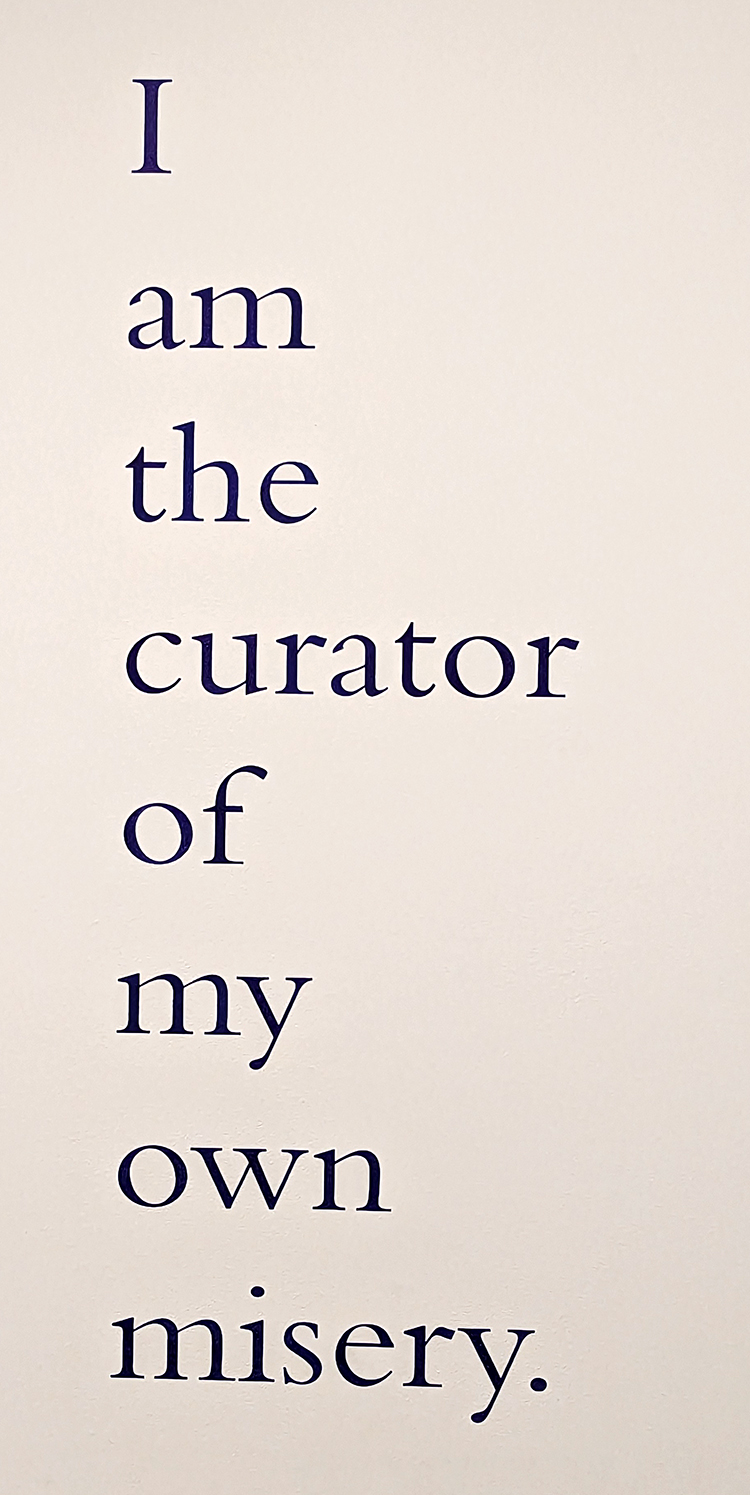

Louise Bourgeois employs text to convey intense feelings of depression and anxiety:

Fear is a recurring theme in Bourgeois’ work, often related to traumatic events in the artist’s life…. Bourgeois spent much of her childhood helping her mother repair tapestries. She wrote: “This sense of reparation is very deep within me. I break everything I touch because I am violent. I destroy my friendships, my love, my children… I break things because I am afraid.”

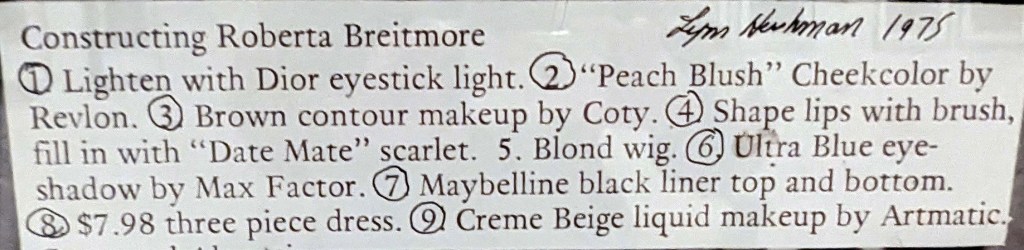

Above left: “Roberta Construction Chart #1 1975,” with detail below, printed in 2009. Above right: “Lay Off & Leave Me Alone 1976.” Both by Lynn Hershman Leeson.

Lynn Hershman Leeson created, performed and documented an alter ego, Roberta Breitmore, from 1973 to 1978 to “focus on the blurriness between fiction and reality.” During her four-year existence, Roberta Breitmore had a bank account and library card, rented an apartment and went on dates. She did not plan for the character to be so developed but “when you start to define how you make somebody real, she needs to be fleshed out and have a history.” “Roberta Construction Chart #1” gives detailed instructions on how to create Roberta’s appearance. It doubles as a visualization of “femininity as masquerade,” highlighting the tropes and traits that tend to be associated with femininity.

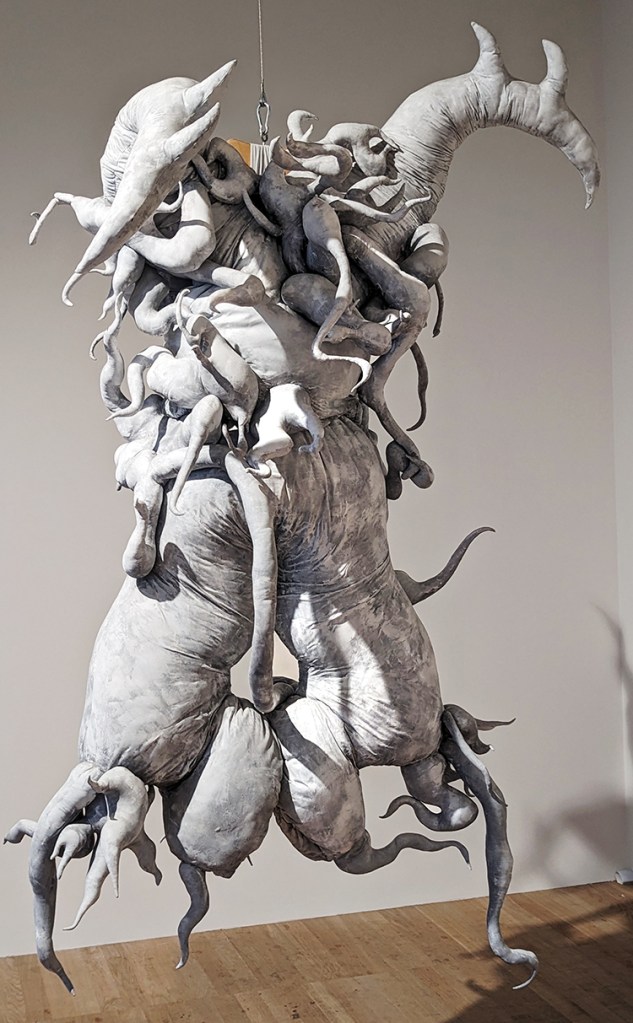

Above: “Untitled (Cravings White),” Lee Bul, 1988, reconstructed 2011.

In 1988, Lee created a series of sponge-stuffed fabric costumes, which she used in some of her earliest performances. Their tentacle-like forms deconstruct society’s expectations of “well-behaved” bodies…. “Untitled (Cravings White)” is a reconstruction of the costume Lee wore during a performance… in South Korea in 1989…. For Lee, artistic expression has always been a means of liberation. Growing up, she was aware of restrictions placed on her body and behavior. Her parents were political dissidents who opposed the oppressive politics of totalitarian rule in South Korea…. While studying sculpture at university she felt pressure to produce work in line with European traditions. Her practice became a means to escape these expectations.

So much of the art at Tate Modern bears the imprint of the artists’ nationalities yet has universal applications. The tragic mortality rate of children during times of war portrayed in Ramirez-Figueroa’s video rises in many places in the world today. Armajani’s story of desperate asylum seekers suffocating in a truck is repeated in South Texas.

The former power station delivers an alternative source of light – art illuminating personal struggles; issues of sexual identity; totalitarian regimes; horrors of war; discrimination; censorship. A multitude of societal issues and ills, all relevant.