Statue of Emanuele Filiberto (1528-1580), Duke of Savoy

Marriages among the titled in Europe generally had larger ramifications than the immediate household.

Once upon a time, the House of Savoy ruled over an Alpine region northwest of Italy, primarily now part of France. In 1051, Otto of Savoy (1023?-1060?) wed Adelaide, a marchioness whose titles brought Turin (Torino) under the House of Savoy.

The land that would eventually become Italy was a battleground in a constant tug of war between France and Spain between 1494 and 1559. When Emanuele Filiberto (1528-1580) inherited the title of the Duke of Savoy in 1553, he found himself somewhat turf-less. Turin was under French control.

Already known as “Testa d’fer” (“Ironhead”) for his early military service to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558) (Charles I of Spain), Emanuele continued to serve the Habsburgs. Emanuele chose sides wisely. The seasoned soldier led the forces of Spanish King Philip II (1527-1598) to a victory at the Battle of Saint Quentin in northern France on the feast day of Saint Lawrence (of the grill) in 1557.

Gradually regaining the former Savoy kingdom from Spain and France [no doubt assisted by his marriage to Margaret (1523-1574), Duchess of Berry and the sister of King Henry II of France (1519-1559)], Emanuele made Turin the capital.

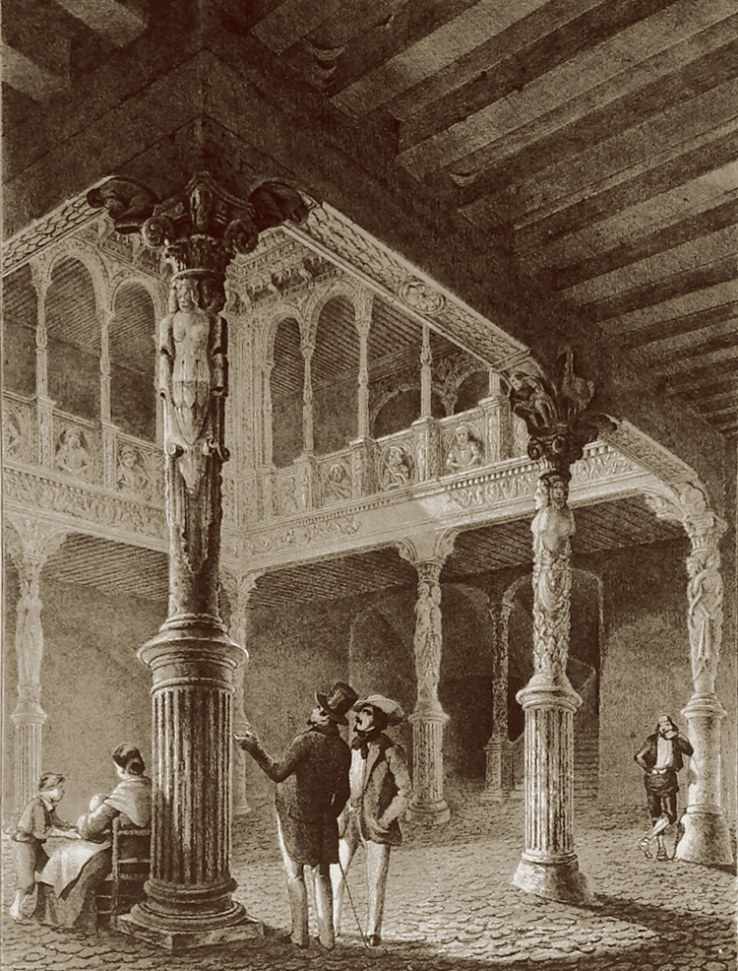

Bishop Domenico Della Rovere (?-1587) had commissioned a palace there as his residence and had the Cathedral of San Giovanni erected next door in 1498. Emanuele made the Bishop’s Palace his own. The Bishop’s Palace was hardly large enough to accommodate the needs of the ruling family, so Emanuele and his successors continually added wings and additional structures. The current façade of Palazzo Reale addressing the sweeping Piazza Castello was the result of an ambitious construction project launched by Regent Maria Christina (1606-1663), a daughter of King Henry IV (1553-1610) of France and the widow of Vittorio Amedeo I di Savoia (1587-1637).

The domed Baroque Chapel of the Holy Shroud, Cappella della Sacra Dinone, was built adjacent to the Cathedral and the Royal Palace at the end of the 15th century during the reign of Carlo Emanuele II (1634-1675). The cherished cloth some claim bears the image of Jesus came into the possession of the House of Savoy in 1453. The relic was damaged by a fire in a chapel in the Savoy’s earlier capital before Carlo Emanuel moved it to Turin.

A major fire again threatened the shroud in 1997, with firefighters smashing its bulletproof glass to spare it. The renovated chapel was not reopened until this past fall, so the shroud itself was tucked away out of sight during our summer visit.

Successive Savoy rulers of the Kingdom of Sardinia resided in the Palazzo Reale until 1865. Victor Emanuele II (1820-1878) , the newly crowned King of Italy, moved out of the residence shortly after commissioning architect Domenico Ferri (1795-1878) to add the elegant Grand Staircase of Honor to the interior.

The Italian Republic claimed ownership of the Royal Palace and its grounds in 1946, and the extensive compound now is operated as Musei Reali Torino.

tomb in Turin Cathedral

detail of painting of Saint Michael in Musei Reali Torino

detail of painting in Musei Reali Torino

Scalone d’Onore in Palazzo Reale

Lion from painting (1528) by Defendente Ferrari, Musei Reali Torino

sculpture in Musei Reali Torino

knight’s tomb, 1382, Musei Reali Torino

Turin Cathedral

painting (1631) by Jan Brueghel II in Musei Reali Torino

Vegezzi-Bossi organ in Turin Cathedral

detail of “Portrait of an Old Man,” Rembrandt van Rijn, 1629, Musei Reali Torino

Scalone d’Onore in Palazzo Reale

Turin Cathedral

polptych of the Shoemakers, circa 1500, Turin Cathedral

Royal Gardens, Palazzo Reale

statue in front of facade of Palazzo Reale

silver bust of Emperor Lucio Vero, 161-169, Musei Reali Torino

detail of painting in Musei Reali Torino

Palazzo Reale

When Emanuele Filiberto made Turin the official capital of Savoy, he also turned his back on some of the family’s French connections by proclaiming Italian the official language of the kingdom. While he changed the spoken tongue, the architecture and design of Turin never lost a strong French accent.