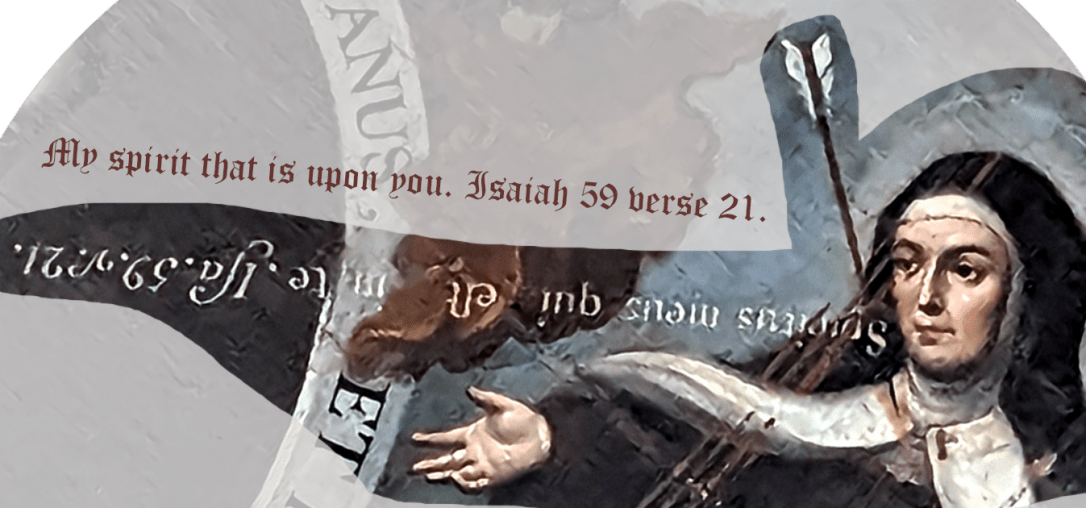

Above: “Annunciation and Saints,” Jose de Paez, Mexican (1727-1790), oil on copper, 1750-1760.

“Spirit & Splendor: El Greco, Velázquez, and the Hispanic Baroque” surveys 150 years of Spanish art leading to the Baroque period with works culled from the collection of the Hispanic Society of America in New York City. Some of Spain’s most renowned and respected artists are represented in this ongoing exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art, but don’t expect much more than a dozen of these works.

What I love are the pieces demonstrating the Baroque style translated by transplants and native-born artisans in the Americas. Artists took advantage of materials available in this so-called “New” World – copper, shells and, of course, more precious metals. They added a magical sheen to art designed to convert “pagans” to the foreign beliefs held by the Catholic conquerors.

Continue reading “Old and New World artistry merge in Hispanic Baroque”